How Hate Crimes Change Lives, Livelihoods And Ways Of Living Conclusion to a six-part investigation by Factchecker.in

05, Feb 2019 | Kunal Purohit

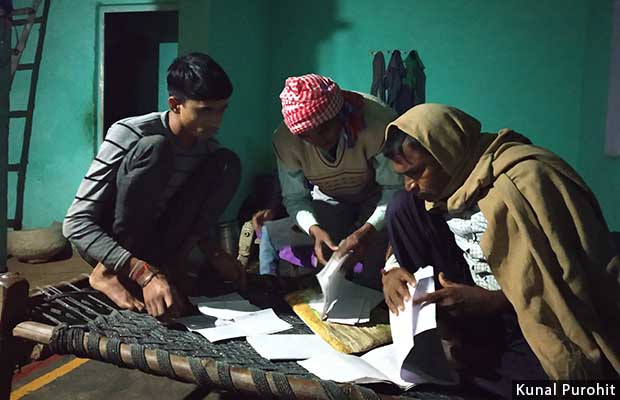

Sonda Habibpur village, Bulandshahr: “Sometimes, I feel like Gabbar Singh,” 44-year-old Shrikrishna said, unable to control his tears and struggling to look for documents in a thick stack, in the faint light of a single bulb in his courtyard.

In the six months since he was publicly assaulted and humiliated, allegedly by mostly upper-caste men, because his son had eloped with a Muslim girl from the village, Shrikrishna’s pile of documents has been growing.

After the elopement in June 2018, a panchayat (village gathering) of Sonda Habibpur was called, where Shrikrishna was asked to ‘return’ the Muslim girl to her family. When he pointed out that the marriage had been registered, Shrikrishna was dragged to the ground from his chair, assaulted with kicks, punches and lathis, and asked to lick his own spit, according to the police First Information Report (FIR). He was also threatened that his wife and daughter would be gang-raped.

“You know how, as soon as villagers realised that Gabbar Singh had come to their village, they would all rush home and shut all doors and windows?” he said, referring to the famous dacoit from the 1975 Hindi classic movie Sholay. “When I walk past, people go into their homes and shut their doors behind them.” Those on the streets, either look away or act busy, he said.

Most of his friends have stopped talking to him, he said, adding, “Some other friends talk to me or allow me into their house only after ensuring that nobody in the village is watching.”

In this concluding part of our six-part series investigating 13 hate crimes in Uttar Pradesh (UP), we examine how oftentimes, hate crimes change lives, and entire ways of living. (Read the previous parts here, here, here, here and here.)

UP accounts for the largest number of crimes stemming from religious bias, recorded in Hate Crime Watch, a database of religious identity-based hate crimes across India from 2009 to 2018.

Traveling across 3,500 km and nine districts over two weeks in December 2018, IndiaSpend found many instances where the ramifications of the crime continued months and years later. For the victims, particularly, a hate crime often led to old friendships being lost, acquaintances un-made, livelihood options snatched.

For the village, new divisions often emerged as communities stopped talking to each other, children stopped playing together, and people found new routes to avoid passing through the other community’s quarters.

In Mau district’s Naseerpur village, where a 68-year-old Muslim man was shot dead in June 2018 when he caught some men throwing pork inside a mosque, the Muslim community is still wary about its interactions with the Hindu community. “We watch what we say when they are around,” said Moen Khan.

In Muzaffarnagar’s Purbaliyan village, where a dispute between teenagers over a cricket match ended in a communal clash and the National Security Act was invoked against four Muslim accused, children of both communities have stopped playing cricket together. “I would always walk through their area earlier. But now, I avoid doing that, even if it means I have to walk for a few more minutes,” said Shalu Kumar, who was allegedly assaulted by a group of Muslims outside her door.

In Kasganj, where a communal clash over a ‘Tiranga Yatra’ taken out by Hindu youngsters left one person dead, many like Qutub Alam are now conscious about their identity. “When I am traveling in buses and trains, heads turn when I greet someone with a “salaam” on the phone.” Alam, an activist with Khudai Khidmatgar, an organisation which works to promote communal harmony, said many within Kasganj’s Muslim community are now conscious about the public display of their beliefs, be it in their clothes or facial hair.

The everydayness of an afterlife

In Sonda Habibpur, Rajkumari, Shrikrishna’s wife, recalled how her neighbours, an upper-caste family, would always help her carry large bundles of hay to her field, 2 km from the village. The neighbours had a tractor and they would use it to transport Rajkumari and the hay.

“After the incident, they asked me to stop accompanying them on the tractor,” she said, “But they offered to continue carrying the hay.” Soon enough, some villagers realised that the neighbours were still helping Rajkumari. Murmurs grew and reached the neighbours’ doorstep. “The next day, they told us they would not be able to carry it for us anymore, because villagers had pressured them to stop,” she said.

In fact, the villagers had warned Shrikrishna’s family of dire consequences if they didn’t leave the village. But an intervention by the local Bajrang Dal unit had ensured they could continue living there, even if under fear.

Rajkumari and Shrikrishna said they were frustrated by their helplessness. The villagers are pushing him to ‘return’ Razia, the girl his son has married. “They have threatened that if I don’t do that, they will implicate me in a false rape case. I am very scared,” he said.

Shrikrishna is the only breadwinner for the family of four. He works as a daily-wage construction labourer. The family’s farming of staple crops like jowar and wheat is barely enough for their own needs, he said, and his oldest son, Shivkumar, 20, the one who had eloped, was their hope.

Now scared for himself and his family, Shrikrishna rushes home before dusk, cutting down on the number of hours he can work. “I am also no longer able to take up a lot of work because most contractors want me to stay and work till late night,” he said.

Earlier, Shrikrishna earned between Rs 250-300 for each day’s work. Since the incident, he has only been managing to work for around 10-12 days each month.

A livelihood lost, acquaintances unmade

Sameddin walked slowly, haltingly and with a slight limp, as he made his way from his house to the mosque, less than 200 m away, for namaaz. His legs, he said, hurt with every step.

Until a few months ago, he had a hectic routine–he ran his farm, did the odd construction job, mostly in the neighbouring Bajhera Khurd village, and tended to his cattle. “I am useless now,” he said. “Ab kuch nahi hota.”

In June last year, Sameddin, 63, became the face of cow vigilantism-driven violence in India when images of him went viral–his beard soaked in blood, his bald pate bloodied and his kurta (long shirt) torn. In the videos, a mob was seen pulling him by his beard, assaulting him and another man. The incident happened on the way from his village of Madhapur to the neighbouring Bajhera Khurd in Hapur district.

The assault left other man, Mohammad Qasim, dead, while Sameddin was left with fractures on his hands, legs and ribs, with his head cracked open.

“I didn’t even realise what was happening,” he said, recounting the afternoon of June 18. He was not even supposed to be at his farm, where the assault happened. A relative had died and he was heading to the funeral. But the car was late, so he decided to quickly go to the farm and feed his cattle.

There, he said he saw a mob of 20-25, armed with wooden staffs, approaching. Soon, they were assaulting Mohammad Qasim, a cattle-trader who was a regular in the two villages, Sameddin said, adding, “I went there to check why they were hitting him. I recognised him immediately and tried stopping them.” Someone in the mob suddenly pointed to him and accused him of also slaughtering cows, he recalled, and then the assailants turned on him.

Sameddin said he remembered being startled to see so many familiar faces. “These were all people who knew me, who I had known. I had even worked for some of them and they knew that I would never slaughter a cow,” he said.

The only consolation, if any, was that those people were not assaulting him. “There were youngsters who I had never seen before. They were all there, hitting me, while these villagers looked on,” he said. They paraded him through the village, all the while assaulting him, he said, adding, “By this time, around 40-45 people had gathered. Anyone who passed me on the way would hit me.”

He kept going in and out of consciousness, he said, and it was only later that he figured out what had happened.

Some people had made announcements in the neighbouring Hindu-dominated Bajnera Khurd village that a cow was being slaughtered in the area where Sameddin’s farm was located. “I was later told that the announcements asked people to immediately gather at the spot and stop the slaughter,” he said. But this was a false rumour, he said.

Police said they had found no signs of cow slaughter at the spot, and had alleged that the lynching was a result of road-rage due to a “minor motorcycle accident”. After that, the Supreme Court had intervened and directed the Inspector General of Police in Meerut to supervise the probe and follow the court’s guidelineson dealing with cases of vigilantism and mob lynchings.

While Qasim died immediately, Sameddin survived and spent more than a month in various hospitals in Hapur and Ghaziabad.

Now that he is back home, Sameddin faces troubling questions. Apart from trying to put the incident behind him, he is also concerned about his family–he is the sole earner for his wife and five children, none of whom are of working age yet. “I have no option but to depend on my family, my brothers and villagers for handouts,” he said.

His assault has caused fresh battlelines to be drawn between the Hindu-dominated Bajnera Khurd and the Muslim-dominated Madhapur villages, separated by fields, an area the locals call a “jungle”.

Even though they live cheek-by-jowl, the villages have seen communally-charged moments. The Hindu and Muslim communities in Bajnera Khurd have been caught in a tussle over a demand to construct a mosque in the village. Once the Muslim community got the authorities’ nod, the Hindus said they would not allow the mosque to have a loudspeaker. The tussle continues to play out.

All this means that even if he does become fit again, which he said is unlikely, Sameddin will never be able to go back to the neighbouring Bajnera Khurd village to work: “When I was being assaulted in that village, no one came to save me, even those who have known me for decades. How can I go back to that village?”

Similarly, he said, people from Bajnera Khurd have stopped passing through his village of Madhapur.

“Now, they take the longer way across,” said a neighbour.

‘The money is a trickle, but I don’t know what else to do’

Haji Aslam had a similar tale to tell–of a livelihood lost in the aftermath of a hate crime.

Aslam has been a meat-trader for over two decades now in Moradabad city. Over two years ago, he said, he was finally able to make a purchase that he had been eyeing for years–a mini-van that would help him start a transportation business.

It all went smoothly, until April 2017 when newly-appointed chief minister Adityanath ordered the closure of all illegal slaughterhouses in the state.

This was bad news for Aslam’s business. “Even the legal ones started fearing because of the panic that the ban created, he said, adding that people stopped hiring his delivery services and his business dried up. Eventually, business got better, he said, but never as good as before.

Then, in August 2018, just after Bakr-Eid, when Aslam was celebrating the festival with his family, a routine delivery changed his life. His driver and cleaner, Aamir and Asim, were transporting animal remains after Bakr-Eid sacrifices when five men on two motorcycles stopped the van, assaulted his employees and, later, set the van on fire. They suspected that the van was carrying cow carcasses.

Aslam said he did all he could to prevent it. He rushed to the police, and a policeman accompanied him to the spot, but, he said, “The cop said there was nothing he could do because the mob was too big. Instead, he told me I should flee or else the mob would kill me too.”

A few days later, he retrieved his van. “It was so badly damaged that I was not able to recognise it,” he said. The garage told him it would cost at least Rs 2 lakh to get the van running again. Aslam was in a fix. The insurance company told him they could pay Rs 1 lakh for the damages, but before that, he would have to pay off his loan on the van. “It was bizarre; I would have to shell out money to get money, at a time when I had no income at all,” he said.

He decided to get the insurance money, no matter what. The hurdle to that were the police, he said, as they did not want to register a case of hate crime. They asked Aslam to register a case of road rage, but Aslam refused. Then, they asked him to not name any of the five men he recognised from the assaulters, and instead say that the men’s identities were unknown to him. “They warned me that I wouldn’t get the FIR otherwise,” he said, adding that he gave in.

Aslam got his insurance money but needs Rs 1 lakh more to get his vehicle back on the road. With his source of income gone, Aslam is now doing odd jobs. His income is a trickle, he said, “But I don’t know what else to do.”

This concludes our six-part series. You can read the first part here, the second here, the third here, the fourth here and the fifth here.

*Feature Image: Sameddin, 63, of Madhapur village in Hapur district in eastern UP spent more than a month in various hospitals in Hapur and Ghaziabad districts after being lynched by a mob on suspicion of slaughtering a cow. He still walks with a limp, and is unable to earn a living. Image by Kunal Purohit.

(Purohit is an independent journalist, writing on politics, gender, development, migration and the intersections between them. He is an alumnus of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.)