Woman, Van Gujjar, Forest Dweller – the roles & intersectionalities in Mariam’s life The Right to a Voice Revisited - Van Gujjar Women & Intersections of Community Mobilization

21, Nov 2019 | Elizabeth Kuroyedov

“One woman standing up against an unjust law is unlikely to achieve much on her own; many women working together, however, are more likely to provoke change” (Rowland 1998)

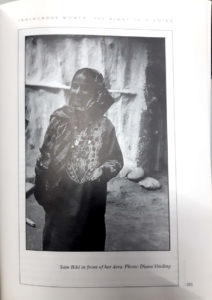

I had first read about a Van Gujjar named Mariam in an article titled “Tribal Women in UP: Challenging the Panchayat System” in Diana Vinding’s book Indigenous Women: The Right to a Voice. When the Van Gujjar community finally gained the right to vote in 1996, Mariam became a ward member for her Gram Panchayat in Mohand.[1] At that time she was only 24, and had learned to read and write through an adult education program held by a local NGO. Mariam realized she could help people with their problems by walking from household to household across the jungle, sharing information from everything to ration cards or village meetings. I showed her the black and white photo from the 1998 article, and she laughed at the younger version of herself: “I went to countries in Europe for meetings about forest peoples you know, near to France. This lady from abroad came to make my passport and take me. I went even though my family said no”. I knew from NGO archives that Mariam had attended United Nations forums on the rights of indigenous peoples as a representative of India. Because Van Gujjars in the 1990s lived within the forests, and not in villages, Mariam’s role was special as not only a woman, but also as a forest-dweller. Her community faced unique needs that couldn’t be channeled through normal gram panchayat routes.

CJP stands with the millions of Adivasis whose lives and livelihoods are threatened by the shocking order by the Supreme Court. We are working to ensure the forest rights of Adivasis in Sonbhadra, Uttar Pradesh, and to deepen our understanding of the Forest Rights Act and support Adivasis’ struggles across the country. Please support our efforts by donating here.

After years of leadership, how did Mariam end up removed from politics, and alone in a resettlement colony? The history of Van Gujjars is complex and varied – each family has a different story, yet some narratives are shared. The creation of Rajaji National Park (RNP) in 1983 secured over 800 square kilometres of jungle as inviolate space, forcing evictions of forest-dwelling people – primarily Van Gujjars.[2] The shift to a sedentary life was incongruent for many (Gooch 1998). Some moved to the colonies willingly, hopeful with the promise of schools, services, and land, while others were coerced. Many Van Gujjars’ names were left of the census for compensation entirely, and they continued to face harassment to leave, while receiving no space in a colony. For those that chose to fight for a life in the forest, harassment, eviction orders, and precarity are rife to this day. Life is negotiated with the Forest Department and authorities, as it always has been since the beginning of British rule and the stationing of guards across the dense forests. The Van Gujjar families who are still residing in the jungles are the ones fighting for livelihood rights under the 2006 Forest Rights Act (FRA), though so far action has been dominated by men.

(Mariam (née Sain Bibi) circa 1996 in Vinding’s book)

The story of the colonies, where Mariam lives, is different. As she muttered to me: ‘no one comes here anymore. There are no meetings or going-ons here’. The expectation is for one family to use their small plot of land, and be grateful for it (despite being denied official ownership papers). Social activism around pastoral and forest rights for Van Gujjars in the colonies is overruled bythe assumption of self-sufficiency and privatized lives conducted on individual parcels of land.[3] The irony is that most children are able to attend school in colonies– a privilege those in the jungles do not have. However, the morale for collective action is comparatively low, as the banality of everyday life and eking out a living is time-consuming.[4]Though Mariam discussed the difficulties of colony life versus the difficulties of being the forest, noting that both were challenging in different ways, she told me it was important that people always connected to the forest.

The intersectionalities that Mariam traverses – as a woman, Van Gujjar, (former) forest-dweller, community leader, and now a widow – made me wonder when and how female leadership can flourish. “Some of the strongest female leaders currently emerging in local and national politics are from neighbouring UP, near Sonbhadra and Dudhwa National Park. Vehemently fighting for recognition of the 2006 FRA, they even brought their case to the Delhi Supreme Court.” The FRA is a landmark piece of legislation which attempts to redress the historical injustices faced by tribal and forest-dwelling people, while granting them rights to live on and use traditional territory.

The act specifically includes gender provisions – “the FRA provides some degree of gender representativeness in the form of joint titles and some clauses for minimum representation for women in various assemblies”(Sharma 2017:58). It is also important to note that the FRA is perhaps the only legislation of independent India that recognizes women’s equal and independent rights over natural resources. Furthermore, it can grant rights to single women, whom otherwise have been conveniently ignored in existing legislation and government schemes (AIUFWP, personal communication). It is crucial to understand these provisions in the FRA as they mean that both Van Gujjar women (and women all across India) can gain equal recognition their forest rights, regardless of their marital or family situation. However, this still opens up a whole new debate about existing patriarchy and inheritance systems. Thus Sharma reminds us that to empower women, rights incorporated under the act need to actually be exercised (2017). There is a large gap to bridge between policy, and action on the ground, for the FRA tobe relevant to women.

Thus, what role can female empowerment play in the FRA, and conversely, can the FRA itself empower women? For Mariam’s sake, we need to critically analyze why Van Gujjar women are left out of mobilizing, while other forest-dwelling tribal women stand at the forefront of the movement. Don’t pastoralist women also stand to gain from conscientization, and the knowledge of their rights as forest-dwellers under Indian legislation? The intersection of education and activism is a critical nexus. This is where confidence, conviction, and the seeds of empowerment begin to grow. Following Paolo Friere, Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, a Maori scholar writes that: “when people learn to read the word of injustice, and the world of injustice, they act against that injustice” (2012:200).

(Mariam in her house – July 2019)

I asked Mariam why she thought Van Gujjar women were not involved in the FRA, or didn’t attend political meetings in general. Of course, there isn’t one easy answer, but she suggested two issues: we need to share and communicate knowledge, and we need to organize around things that are directly relevant to women. To encourage women to try something new, they need a reason that is theirs alone to step out of the house. Somewhere where their presence feels truly necessary, and they’re not just another voice at the back of the room. Diversity is being present at a meeting, inclusion is having a voice, but belonging is having that voice valued.

The adivasi women of Sonbhadra have begun to bridge the gap between policy provisions and action through collectively organizing and forming women’s unions. Similarly, a fascinating study and analysis from Bangladesh by Ryan Higgitt also points in the direction of women collectively organizing for change. This is why: most rural women in South Asia are positioned as dependents, so each woman on her own possesses little prospect of demanding justice. Instead, we need a network of women who have a shared sense of experience. Conscientization and organization can mobilize the only resources rural women do have: their capacity to resist and transform through collective strength. According to Higgitt, “insofar as women’s dis-empowerment is collectively enforced, collective action is assumedly vital” (2011: 113). In Bangladesh, the organization Nagorik Uddyog brings different rural women together to confront a common challenge: inaccessibility to the traditional rural dispute and justice system, shalish. As women from all sections of rural Bangladeshi society are excluded from shalish, NagorikUddyog helps form grassroots networks where women together demand to be involved in shalish (Higgitt 2011). The idea was massively successful.

Take this example to North India: if all Van Gujjar women are excluded from political activism and from the FRA, here too their collective dis-empowerment requires collective action. I believe individual women like Mariam are vital as catalysts and role models for their fellow female community members. However, today no meetings are even held in Pathri, and no NGO support is on the ground. What if Mariam had the collective support of other Van Gujjar women? Support to initiate their own meetings, trainings, and discussions around topics which they deem to be important? If this can happen, I envision Van Gujjar women with the capacity to resist and transform through their collective strength, just like in Sonbhadra or Bangladesh. When we recognize, appreciate, and accept passionate women like Mariam, it can motivate them to take action.

As controversy and legal battles over the FRA and fates of forest-dwelling people resurface in the media and political discourse, it is crucial to think about the forms and possibilities of social action, especially among women, and especially among pastoralists, whose complex identities and histories are left out of the mainstream discourse. Van Gujjar women do not only deserve the right to a voice, but also the right to make that voice be heard, and belong.

(The author is a senior academic with the MSc. Anthropology, Environment, & Development, University College London)

References

Gooch, P. 1998. At the Tail of the Buffalo: Van Gujjar Pastoralists Between the Forest and the World Arena. Lund: Lund University Press.

Vinding, D. 1998. Indigenous Women: The Right to a Voice.Copenhagen: IWGIA.

Higgit, R. 2011. Women’s Leadership Building as a Poverty Reduction Strategy: Lessons from Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Development, 6(1), 93 –119.

Sharma, A. 2017. The Indian Forest Rights Act (2006): A Gender Perspective. Indian Journal of Women and Social Change. 2(1), 48-64.

Tuhiwai-Smith, L. 2012 [1999].Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

[1]At that time, Mohand was part of Uttar Pradesh (UP) as Uttarakhand was only created in 2000.

[2]It is important to note that other village communities residing near the park were adversely affected, though the focus of this article is specifically about Van Gujjars.

[3]Individual plots of land are completely contrary to traditional pastoral practice, where wide swathes of land are used rotationally, seasonally, and collectively, often with informal and flexible boundaries. Leaving the forest and soil to regenerate when it is tired, and collectively tending to the growth of desired plants throughout the jungle, are both examples common practices.

[4]It is often hard to make ends meet for many families in the colonies, as the ability to gain more land is impossible, and families grow. Mariam also faced difficulties with her bank account, receiving pension, and other bureaucratic technicalities. Thus it is difficult to expect people to have time to engage in things outside income generation.

(Image courtesy – Indian Express)

Related:

Compilation of Forest Rights Act, Rules, and Guidelines

Overview of the law pertaining to land and governance under the Fifth Schedule