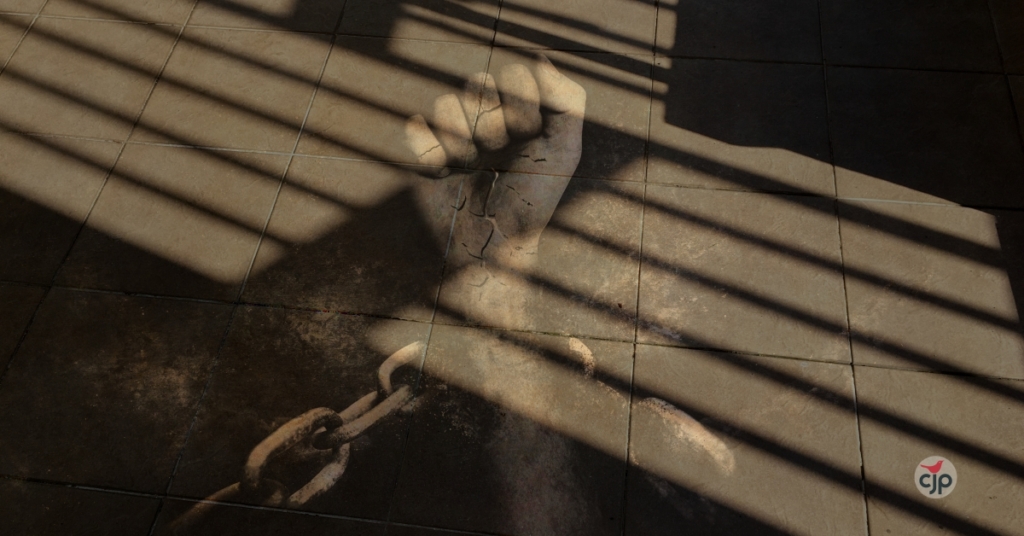

Preventive Detention: Two judgements, two contrasting views, one judge While one judgement upholds personal liberty, the other justifies preventive detention

03, Mar 2022 | Sanchita Kadam

The High Court of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh on February 25, 2022, delivered two judgments with contrasting views on preventive detention. It is important to juxtapose the two judgments of Justice Tashi Rabstan, who has on one hand taken a view in the interest of safeguarding personal liberty, and on the other, has given complete justification in favour of preventive detention.

Certainly in the case of Shabir Malik, he was detained on the basis of older cases and on apprehension of him being a stone pelter, while in the case of Farhat Mir, he was detained for being a timber smuggler. The facts and circumstances in both cases are different, but the views expressed in both these judgements delivered on the same day are noteworthy.

Each of these judgements were read down to the last word to juxtapose how one judge has taken starkly contrasting views when it comes to personal liberty without giving much emphasis on the merits or the circumstances in each case.

Shabir Malik’s petition

The petitioner, Shabir Ahmad Malik sought quashing of the October 17, 2021 order of the District Magistrate, Anantnag placing him under detention. The petitioner’s counsel, Syed Musaib argued that the FIRs relied upon for passing the said order were registered way back in 2013 and 2016 and asserted that the grounds for detention are vague, non-existent and hence, the order is unjustified and unreasonable. He further submitted that the detaining authority has not attributed any fresh activity which would have warranted passing of the order of detention. He also stated that all documents required by the detenu to make an effective representation were not provided to him, thus infringing the constitutional right guaranteed to the detenu under Article 22(5) of the Constitution.

Sustenance of dignity

The court said, “The reverence of life is insegragably concomitant with the dignity of a human being who is basically divine, not obsequious. A human personality is indeed with potential infinitude and it blossoms when dignity is sustained. The sustenance of such dignity has to be the superlative concern of every sensitive soul. The essence of dignity can never be treated as a momentary spark of light or, for that matter, “a brief candle”, or “a hollow bubble”.”

“Reverence for the nobility of a human being has to be the cornerstone of a body polity that believes in orderly progress. But, some, the incurable ones, become totally oblivious of the fact that living with dignity has been enshrined in our Constitutional philosophy and it has its ubiquitous presence and the majesty and sacrosanctity dignity cannot be allowed to be crucified in the name of precautionary incarceration,” the court further said.

Detention: Preventative or punitive?

The court reminded that Article 22(3)(b) is only an exception to Article 21 of the Constitution. It observed:

An exception is an exception and cannot ordinarily nullify the full force of main rule, which is right to liberty in Article 21 of the Constitution. Fundamental rights are meant for protecting civil liberties of people and not to put them in immurement for a long period, shorn of recourse to a lawyer and without a trial. It is all very well to say that preventive detention is preventive not punitive. The truth of the matter, though, is that in essence a detention order of three months, or any other period(s), is a punishment of that particular period’s incarceration. What difference is it to detenu whether his immurement is called preventive or punitive.”

Prevention detention repugnant to democratic ideas

The court further observed:

“Preventive detention is every so often described as a ‘jurisdiction of suspicion’, the detaining authority passes the detention order on the subjective satisfaction. The preventive detention is, by nature, repugnant to the democratic ideas and an anathema to the rule of law. Since Clause (3) of Article 22 specifically excludes applicability of clauses (1) and (2), the detenu is not entitled to a lawyer or the right to be produced before a Magistrate within 24 hours of arrest. To prevent misuse of this potentially dangerous power the law of preventive detention has to be strictly construed and meticulous compliance with procedural safeguards, howsoever technical, is mandatory and vital.”

Procedural requirements

The court observed that “procedural requirements are only safeguards available to a detenu, for the reason that the Court is not expected to go behind the subjective satisfaction of detaining authority.” In Abdul Latif Abdul Wahab Sheikh v. B. K. Jha and another (1987) 2 SCC 22, the Supreme Court had held that procedural requirements are, therefore, to be strictly complied with, if any value is to be attached to the liberty of the subject and the Constitutional rights guaranteed to him in that regard.

The court observed that “whenever the preventive detention is called in question in a court of law, first and foremost task before the Court is to see whether the procedural safeguards guaranteed under Article 22(5) of the Constitution of India and the Preventive Detention Law pressed into service to slap the detention, are adhered to.”

Right to be furnished documents

The court held that since preventive detention is a serious invasion of the personal liberty, it should be ensured that in compliance with Article 22(5), the detenu be furnished with the particulars of the grounds of his detention, sufficient to enable him to make a representation, which on being considered may give relief to him. The Article 22(5) states, “When any person is detained in pursuance of an order made under any law providing for preventive detention, the authority making the order shall, as soon as may be, communicate to such person the grounds on which the order has been made and shall afford him the earliest opportunity of making a representation against the order.”

The Supreme Court in Khudiram Das v. State of West Bengal and others (1975) 2 SCC 81, observed that Article 22(5) insists that all the basic facts and particulars which influenced the detaining authority in arriving at requisite satisfaction leading to passing of the order of detention, must be communicated to detenu.

In Ganga Ramchand Bharvani v. Under Secretary to the Government of Maharashtra and others (1980) 4 SCC 624, the Supreme Court observed thus,

The mere fact that the grounds of detention served on the detenu are elaborate, does not absolve the detaining authority from its constitutional responsibility to supply all the basic facts and materials relied upon in the grounds to the detenu. In the instant case, the grounds contain only the substance of the statements, while the detenu had asked for copies of the full text of those statements. It is submitted by the learned Counsel for the petitioner that in the absence of the full texts of these statements which had been referred to and relied upon in the grounds ‘of detention’, the detenus could not make an effective representation and there is disobedience of the second constitutional imperative pointed out in Khudiram’s case. There is merit in this submission.”

In the case of Ramachandra A. Kamat v. Union of India and others (1980) 2 SCC 270, the Supreme Court clearly held that even the documents referred to in the grounds of detention have to be furnished to the detenu.

Is detention warranted?

The court considered that even though the allegations may be serious and the offences allegedly committed by detenu attract the punishment under the prevailing laws but that has to be done under the prevalent laws and taking recourse to the preventive detention laws would not be warranted. It observed,

The detention cannot be made a substitute for ordinary law and absolve the investigating authorities of their normal functions of investigating the crimes, which the detenu may have committed. After all, preventive detention cannot be used as an instrument to keep a person in perpetual custody without trial.”

About procedural safeguards, the court further said,

The Constitutional and Statutory safeguards guaranteed to detenu are to be meaningful only if detenu is handed over material referred to in grounds of detention that lead to subjective satisfaction that preventive detention of detenu is necessary to prevent him from acting in any manner prejudicial to the security of the State or public order and further it is ensured that the grounds of detention are not vague, sketchy and ambiguous so as to keep the detenu guessing about what really weighed with the detaining authority to make the order.”

Delay between offence and detention

“When there is undue and long delay between the prejudicial activities and the passing of the detention order, the court has to scrutinise whether the detaining authority has satisfactorily examined such a delay and afforded a tenable and reasonable explanation as to why such delay has occasioned, when called upon to answer and further the court has to investigate whether the casual connection has been broken in the circumstances of each case,” the court said

Detention not alternative to legal process

In V. Shantha v. State of Telangana & ors, AIR 2017 SC 2625 the Supreme Court has held that preventive detention of a person by a State after branding him a ‘goonda’ merely because the normal legal process is ineffective and time-consuming in ‘curbing the evil he spreads’, is illegal. Preventive detention cannot be resorted to when sufficient remedies are available under the general laws of the land for any omission or commission under such laws, the Supreme Court observed.

The court stated that classifying the detenu as a ‘stone pelter’ is not sufficient for preventive detention. The court reiterated that such a detention cannot be made a substitute for the ordinary law and absolve the investigating authorities of their normal functions of investigating the crimes which the detenu may have committed.

The court thus quashed the detention of the petitioner and directed that he be released if not required in any other offence.

The complete judgement may be read here:

Farhat Mir’s petition

In this case, the petitioner Farhat Mir was placed under preventive detention for the offence of smuggling timber. It was alleged that the detenu is involved in the timber smuggling by chopping down of the trees, encroaching the forest land, setting the forest fires and cultivating the profitable crop on the forest land.

The petitioner’s counsel Senior Advocate NH Shah argued that the authorities with preconceived mind sought the detention order to be passed without applying his mind and without any due procedure and that impugned detention order has been seemingly passed upon the dictates of police authorities. It was further submitted that the detenu was not informed that within what timeframe he can make a representation against the detention order to the detaining authority in total violation of the rights of the detenu as guaranteed under Article 22 of the Constitution.

The aim of preventive detention

“Its aim and object are to save the society from the activities that are likely to deprive a large number of people of their right to life and personal liberty. In such a case it would be dangerous for the people at large, to wait and watch as by the time the ordinary law is set into motion, the person, having the dangerous designs, would execute his plans, exposing the general public to risk and causing colossal damage to life and property. It is, for that reason, necessary to take preventive measures and prevent a person bent upon to perpetrate the mischief from translating his ideas into action. Article 22 of the Constitution of India, therefore, leaves scope for enactment of the preventive detention laws,” observed the court.

The court further justified detention by saying, “The compulsions of the primordial need to maintain order in society, without which enjoyment of all the rights, including the right of personal liberty would lose all their meaning, are the true justifications for the laws of the preventive detention.”

The court after perusal of the detention record observed that the order was approved by the government in time and the detenu was informed to make a representation before the Government as well as the detaining authority. Further, the material relied upon by the detaining authority while passing the impugned order of detention was also provided.

Justifying detention

“The order of detention is based on a reasonable prognosis of the future behaviour of a person based on his past conduct in the light of the surrounding circumstances. The power of preventive detention is exercised in reasonable anticipation. It may or may not relate to an offence. It does not overlap with the prosecution even if it relies on certain facts for which the prosecution may be, or may have been, launched,” the court said.

The petitioner had argued that no material has been disclosed by detaining authority in grounds of detention to establish existence of any exceptional reasons justifying recourse to preventive detention. “If object of making the order of detention is to prevent commission in future, of activities injurious to the community, it would be a perfectly legitimate exercise of power to make the order of detention,” the court observed. The court pointed out that the detaining authority cannot always be in possession of full detailed information when it passes the order of detention and the information in its possession, may fall far short of legal proof of any specific offence, although it may be indicative of a strong probability of the impending commission of a prejudicial act.

Subjective satisfaction cannot be examined

The court was of the view that it cannot sit in the place of the Government and try to determine if it would have come to the same conclusion as Government since preventive detention is a matter for the subjective decision of the Government and that cannot be substituted by an objective test in a court of law. It said,

This Court, while examining the material, which is made on the basis of subjective satisfaction of detaining authority, would not act as a ‘court of appeal’ and find fault with the satisfaction on the ground that on the basis of material before detaining authority, another view was possible.”

While the court did mention that personal liberty is one of the most cherished freedoms, it stated that when individual liberty comes into conflict with an interest of the security of the State or maintenance of public order, then the liberty of the individual must give way to the larger interest of the nation.

The court further said, “Subjective satisfaction of a detaining authority to detain a person or not, is not open to objective assessment by a Court. A Court is not a proper forum to scrutinise the merits of administrative decision to detain a person.”

The court thus dismissed the petition to quash the detention order.

The complete judgement may be read here:

Related:

Siddique Kappan: A journalist who has spent 500+ days in prison, for just doing his job

Guj HC orders release of suspected foreigner detained without being given opportunity to be heard