Everyday Atrocity: Mapping the normalisation of violence against Dalits and Adivasis in 2025 An evidence-based half-year chronicle of caste atrocities, tracing the structural, symbolic, and state-enabled violence against Dalit and Adivasi communities

05, Jul 2025 | CJP Team

When we are working, they ask us not to come near them. At tea canteens, they have separate tea tumblers and they make us clean them ourselves and make us put the dishes away ourselves. We cannot enter temples. We cannot use upper-caste water taps. We have to go one kilometre away to get water… When we ask for our rights from the government, the municipality officials threaten to fire us. So, we don’t say anything. This is what happens to people who demand their rights.

— A Dalit manual scavenger, Ahmedabad district, Gujarat

Thevars [caste Hindus] treat Sikkaliars [Dalits] as slaves so they can utilise them as they wish. They exploit them sexually and make them dig graveyards for high-caste people’s burials. They have to take the death message to Thevars. These are all unpaid services.

— Manibharati, social activist, Madurai district, Tamil Nadu

In the past, twenty to thirty years ago, [Dalits] enjoyed the practice of “untouchability.” In the past, women enjoyed being oppressed by men. They weren’t educated. They didn’t know the world… They enjoy Thevar community men having them as concubines… They cannot afford to react; they are dependent on us for jobs and protection… She wants it from him. He permits it. If he has power, then she has more affection for the landlord.

— A prominent Thevar political leader, Tamil Nadu[1]

CJP is dedicated to finding and bringing to light instances of Hate Speech, so that the bigots propagating these venomous ideas can be unmasked and brought to justice. To learn more about our campaign against hate speech, please become a member. To support our initiatives, please donate now!

“Dalit” is a term first coined by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, one of the architects of the Indian constitution of 1950 and revered leader of the Dalit movement. It was taken up in the 1970s by the Dalit Panther Movement, which organized to claim rights for “untouchables,” and is now commonly used by rights activists.[2] Violence against this section of the Indian people, Dalits, who constitute (2011 Census figures) 16.6 per cent of the population is both societal, systemic and instructional cutting through all intersectionality’s. This analysis and graphic visualisation looks at this phenomenon, not contain, today normalised, in 2025.

On June 24, 2025 — The Indian Express reported, “Nine people have been detained after a mob forcibly shaved the heads of two Dalit men and forced them to crawl over allegations of cow smuggling in Odisha’s Ganjam district. According to the police, the victims had bought a cow and two calves and were returning home when a mob accosted them in Kharigumma village under Dharakote police limits and demanded Rs 30,000. When the men expressed inability to pay, the mob allegedly beat them up, forcibly shaved their heads, made them crawl and had them drink sewage water. A video purportedly shows the two men crawling with grass clamped between their teeth as some men follow them. The group also took away cash of Rs 700 from them and their mobile phones, police said.” This is not, unsurprisingly, a stray or isolated event – with CJP recording 113 incidents of anti-Dalit atrocities from the month of January to June.

The all-pervasive caste system has long cemented itself as a fortifying structure of Indian society. With a state machinery that openly runs on a proto-fascist, pro-Hindutva model – the continued marginalisation of Indian minorities has become, in dystopian fashion, extremely normalized in the day-to-day news cycle. This report tries to trace this normalisation by forming understandings of the historical, typological and the systemic nature of the violence enacted upon Dalit and Adivasi/tribal individuals in India by considering data consolidated within the months of January-June.

Historical & Structural Context – Everydayness of Caste Atrocities

One must always remember that caste atrocities in India is not a regime-specific conundrum, and that while there is a strong relationship between the (present, ideologically driven) Hindutva state and the exacerbation of such atrocities — India has had a long, shameful history where the caste system has been entrenched into every facet of living. Ania Loomba, in The Everyday Violence of Caste, writes: “Caste violence in India is one of the most long-standing instances of the routinisation of violence, predating European colonialism although not unshaped by it, and now firmly enmeshed within the new global order. Despite untouchability being constitutionally abolished in 1950, caste oppression is pervasive today. Over 160 million Untouchables- or Dalits- are subject to different forms of discrimination: they are denied access to places of worship, clean water, housing, and land; their children are still kept out of, or ill-treated within, schools; they are forced into menial and degrading occupations, notably manual scavenging; and, despite a governmental policy of affirmative action, they remain largely excluded from the country’s businesses, educational establishments, judicial services, and bureaucracy.1 If violence against lower castes and outcastes is rendered banal by being woven into the fabric of everyday life, it is also conducted via spectacular acts. Dalits are raped and murdered for daring to aspire to land, electricity, drinking water, and to non-Dalit partners. Inter-caste marriages, especially those between lower caste men and women of higher castes, result in murders, kidnapping, and the public punishment of such men and (often) the women involved. Dalit women remain subject to constant sexual assault by upper caste men. In general, caste segregation shapes India’s rural landscape, as well as large parts of its urbanity.”

In Indian society, the entrenched hierarchy of caste is all-pervasive, affecting the lives of Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi individuals – through popular and institutional violence at different scales. This routinization, that Loomba writes about, is a process that has spanned centuries: almost from the birth of Hinduism, as a religion — and therefore, the committing of atrocities has been naturalized into social order. We could invoke Martin Macwan, who rightly wrote, in 2001, “The systematic elimination of six million Jews by Nazis hit us hard on the face because it took place in such a short span of time. In the case of Dalits, though the “genocide” has been systemic, it has taken place at a slow pace. The current government statistics of murder, rape, and assault that Dalits are subjected to paint a horrible picture if extended to a history of 3000 years. We have reason to believe that approximately 2,190,000 Dalits have been murdered, 3,285,000 raped and over 75,000,000 assaulted.”

Methodology and Data Sources

In this report, we use data from CJP’s own database, and from multiple reliable think-tanks, non-governmental organizations, news outlets, legal filings and academic publications. We also take into account cross-verified posts from social media accounts that specialise in hate-watching, reporting on Dalit and Adivasi issues, etc. The data from the National Crime Records Bureau’s own publications has also been used for contextualization.

We have attempted to classify this data on the basis of geography, types of violence, and looked into institutional response: from law enforcement and respective state governments’ attitudes to caste-based violence. The report endeavours to be grounded in intersectionality, taking into account the changing metrics of class and gender, which quite obviously come into play while discussing caste.

Typology of Violence: Key Patterns from 2025

- Violence Against Adivasis and Tribal Populations

Tribal and Adivasi lives have also been rife with violence within the country – being victimised by large scale unrest, institutional crackdowns, and targeted attacks in different parts of the country. While encounters have intensified in the BJP ruled state of Chhattisgarh, and CRPF camps being set-up in the “most vulnerable Maoist locations”, the CPI (Maoist) party has proposed peace talks with the government. This was followed by 200 civil rights groups and individuals urging for the government to show their intent at reaching a ceasefire and some form of agreement. The statement from the signatories of these organizations is as follows,

“It is now exactly 20 years since the state sponsored and now banned Salwa Judum began in Bastar, causing enormous misery in terms of people killed, villages burnt, rapes, starvation, mass displacement and other forms of violence. Since then, the villagers of Bastar have known little peace. They barely returned to their villages when they were faced with Operation Green Hunt and successive operations. Since 2024, under the name of Operation Kagaar, over 400 people have been killed (287 in 2024, 113 in 2025).i While the exact numbers of civilians killed is unknown, given that several of those claimed as Maoists have been identified by villagers as civilians, it is evident that civilians are being disproportionately affected ii. An Article 14 estimate between 2018 and 2022 counts more civilians (335) killed than security personnel (168) and Maoists (327). iii 2024 saw several incidents of children being killed. SATP gives the breakup for 2025 to 15 civilians, 14 security forces and 150 Maoists. The forces have got Rs. 8.24 crore as rewards for these killings.”

Parallely, the centre’s failure at dealing with ethnic clashes in Manipur has drawn widespread criticism from the states – according to Human Rights Watch – at least five people have died and scores injured, including security force members, in recent clashes, alone. On March 8, a man was killed and several were injured in Kangpokpi district when violence broke out after the authorities attempted to restore transportation connections across the state. On March 19, another man was killed following clashes between two tribal communities in the state’s Churachandpur district. The violence, so far, has killed more than 260 people and displaced over 60,000 since May 2023.

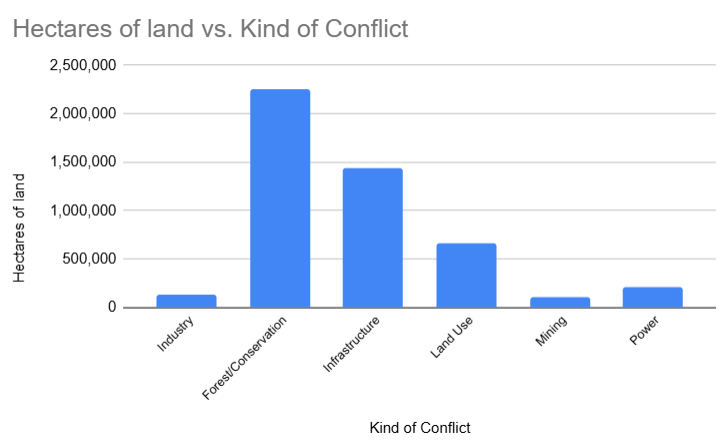

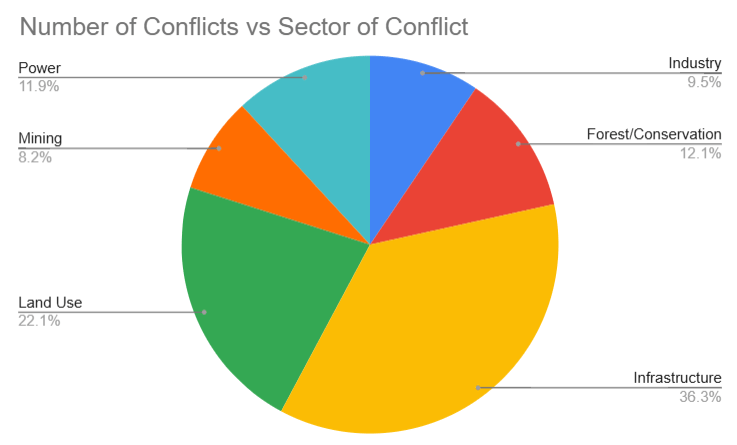

Land conflicts have also followed tribal populaces – according to Land Conflict Watch, there are 962 reported ongoing land conflicts in their Conflicts Database. Out of these 116 conflicts are in the Conservatory and Forestry sector, with 459,735 people currently affected. The following charts shows the shares of the kind and numbers of conflict going on in the country, in context of land area and people affected — based on data available from the Conflicts Database of the Land Conflict Watch website.

Kind of Conflict vs. Hectares of Land Conflicted

Number of Conflicts in relation to Sector

Number of Conflicts in relation to Sector

As mentioned before, while state actors do perpetrate a huge share of the violence borne by the tribal populations in India – this does not mean that they are spared from acts of targeted violence by upper-caste perpetrators.

CJP recorded 74 incidents of anti-Christian violence in India in 2025— out of which, 48 were cases of harassment, assault and violence under the pretext of allegations of conversion. While not all of these were mandated on Adivasi individuals, a bone of contention that the propagators of the formulation of the Hindutva state has with the so called “Christianisation of tribals/Adivasis” has been rooted in ideas of “foreignness”. It is also manifest in the Adivasi v/s Vanvasi formulation, with the RSS and it’s multiple outfits like the Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram committed to an alteration/manipulation of the pre-Hindu, Adivasi identity, threatened as they are by the ‘original inhabitant’ argument, before the onset and domination of the “Vedic period” in early Indian history.

A recent book, among several earlier studies on the subject, Kamal Nayan Choubey’s Adivasi or Vanvasi-the politics of Hindutva, observes, “Akhil Bhartiya Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram, popularly known as Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram or VKA is the tribal wing of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). As the largest tribal organization in the country, it works in many areas of Kerala, Jharkhand and the North-east of India. Till the late 1970s, VKA’s work was limited to a few districts of Chhattisgarh (then Madhya Pradesh), Jharkhand (then Bihar), and Odisha but it has gradually and continuously expanded its footprint in different parts of the country…. It is noteworthy that from its inception VKA focused on spreading Hindu values by organizing religious rituals in tribal areas and working in the area of education and hostels.” Academic works and publications on the methods of RSS’ penetration among tribals stress on the Ekal School, an education model that not just imposes “caste Hindu practices” among Adivasis who’s traditional belief systems are animistic, but also instils an element of the “outsider other” when it comes to the Indian religious minority, the Christian or the Muslim.[3] Studies of the syllabus taught in these schools also reveals how the “project was intended to spread disharmony”. Subsequent incidents of targeted violence in several Adivasi-dominated areas of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh has empirically shown Adivasis adopting an assumed adversarial role against India’s religious minorities.[4][5]

The Washington Post reported in February 2025 about multiple grassroots evangelical pursuits of the grassroots organizations of the far Hindu right, under the pretext of developmental work – has been trying to induct millions of tribal people who have been outside mainstream religion, or are Christians. All of this is conducive to the central ahistorical one-dimensional belief that the converted Adivasi has been stolen away from the “homogenised Hindu original-state” — ignoring all dimensions of oppression, dynamics of caste and struggle, and presenting a dichotomy of the “homegrown” Hinduism and the “foreign” Christianity – ignoring the neo-colonial model that has been replicated by Hindutva outfits. Satianathan Clarke writes for the Harvard Theological Review, “First, Christians, through their sustained service among the Adivasis, “enjoy considerable appreciation of and support for their work from the local population.”37 This presents an obstacle for the Hindutva organizations to infiltrate the Adivasi areas. “The advance of the Parivar [Network of Hindutva organizations] in the tribal area is, therefore, possible only if the Christians are discredited and displaced.” Second, Christians are targeted because of the secular position they have increasingly taken over the last decade. In the context of Hindu communalism’s fascist potential, Christians present a counter model in their “reaching out to secular, liberal and Left formations for joint initiative.” Christianity, especially among Dalits and Adivasis, must be stopped at any cost from being presented as an alternative option to Hindutva. Panikkar’s discussion, I believe, is in line with my claim that Christians are being persecuted because their work among the Dalits and Adivasis is perceived as an effort to thwart the homogenizing aim of Hindutva.”

Besides these, there have been incidents of harassment, and torture, where tribal women have been gang raped, Adivasi people repeatedly subjected to humiliation and assault at the hands of upper caste individuals and community members.

Anti-Dalit Violence

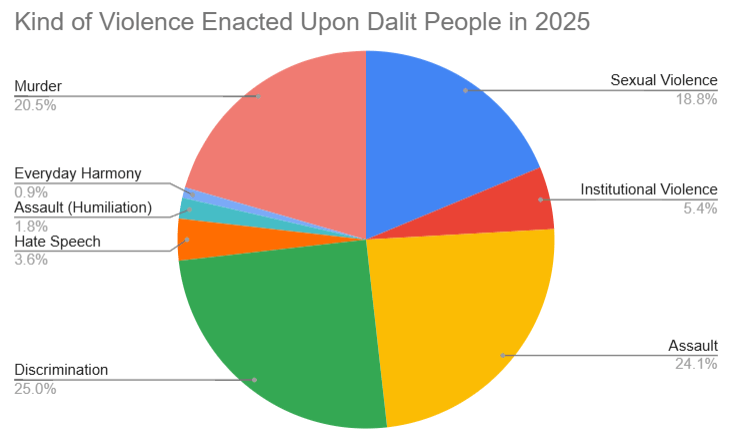

Between the months of January and June, CJP recorded 113 incidents of caste atrocities on Dalit individuals across different states in India. A general categorisation of this violence can be seen as follows.

This chart tells us that out of the 113 cases, assaults had the highest rate of incidence – with a combined percentage of 25.9% [Assault and Assault with the intent of humiliation, combined], followed by high rates of harassment in the form of discrimination – and finally, more grievously, murder and sexual violence – at 20.5% and 18.8% respectively. What is essential for us to remember, is the fact that caste atrocities cannot be neatly separated in clinically placed boxes of violence. Each category is deeply inter-related with the others, and Dalit people, as individuals and as collectives, go through multiple enactments of violence.

Snigdha Adil writes, “The confluence of the material (the body) and the symbolic (language) suggests that the recurrent embodied experiences of exclusions manifest on the caste body and are consequently, articulated; these orations, then, reproduce marginalisation in the lived reality. Such rhetoric is internalised by the Dalit individual, and imposes a state of humiliation and self-loathing upon them. Chakrabarty asserts that the Dalit person’s sense of their body is refracted through a third-person consciousness; it is impossible for the Dalit individual to imagine a reprieve from the corporal schema of degradation that is imposed upon it by the ‘upper’-castes. The process of discrimination as it is enacted against the body and, thereby, shapes (or contorts) it entails the construction of the Dalit (non-)self. To comprehensively understand the agents and methodologies of discrimination within the context of modernity – which is characterised by social mobility through urbanisation, education, and employment opportunities beyond the caste-specific occupational fields – as opposed to the feudal past, one must adopt an archaeological approach towards an understanding of the practice of Untouchability. The camouflage of caste discrimination into innocuous practices to detect and distance the ‘lower’-caste individual despite the external performance of progressive beliefs unveils the “inalterability of the ‘Indian mind’” (Archaeology of Untouchability 219). As one is compelled to operate in ambiguous spaces of social exchange wherein the identity of those one engages with is unknown, exacerbated by the need to concomitantly maintain a façade of transcendence from outdated religious codes as well as the superiority of the self; one must evolve new codes and signifiers that accommodate plausible deniability. … In the same vein, it may be argued that the social, material, and personal deprivation of Dalits is not inherent but maintained through the performance of caste practices and symbols.”

Therefore, we can also make two conclusions from what Adil writes, and a historical study of Brahminical violence on Dalit communities: one, that the nature of attacks is aimed to be a debilitating force on the dignities and the abilities— because the intent behind these attacks is to impinge upon the Dalit sense of self and identity – both individual and communal. Two, the style and the formations of attacks have modified themselves over time while maintaining the same antediluvian spirit of oppression – manifesting through different forms of ostracisation, causation of humiliation, and outright physical and psychological violence.

Structural and systemic violence, cultural and symbolic assertion, physical and sexual violence, caste slurs and verbal abuse, exclusion and boycott are all different forms of atrocities affecting Dalit individuals in India. If we were to look at the data for just the month of June, we would see that all of them can be put into the aforementioned “categories”, or exist at the intersections between two or many of them.

1st June, 2025: A Dalit family was attacked by a group of men with sticks and rods during a wedding ceremony on Friday night, police said. The attackers reportedly shouted caste-based insults, angry that a Dalit family was using a marriage hall in Rasra, Uttar Pradesh. Raghvendra Gautam, the brother of one of the injured men, filed the police complaint. He said, “We were celebrating happily when suddenly a group of men stormed in and shouted, ‘How can Dalits hold a wedding in a hall?’ Then they started beating everyone.” The attack happened at the Swayamvar Marriage Hall around 10:30 p.m. Two people, Ajay Kumar and Manan Kant, were badly hurt and are now in the hospital.

June 1, 2025: A minor Dalit girl who was raped and found with nearly 20 knife wounds in Muzaffarpur died at the Patna Medical College and Hospital on Sunday, June 1, 2025. The 11-year-old was transferred to Patna on Saturday for better medical treatment, but was allegedly left in pain inside the ambulance outside the Patna hospital for about five hours, and was admitted after intervention by Bihar Congress president.

June 4, 2025: A Tribal woman was gang-raped and then her intestines were pulled out by inserting hands in her rectum, incident happened in Khandwa city of Madhya Pradesh.

June 10, 2025: Dhanush, a Dalit youth employed in an IT firm in Coimbatore, was reportedly in a relationship with a woman from a different religion. He was found hanging at his lover’s residence.

June 18, 2025: Due to not being able to repay a loan of 80 thousand, a Dalit woman was tied to a tree, humiliated and beaten in front of her own child, the child will not be able to forget this shock for the rest of his life, the incident is from Kuppam in Andhra Pradesh. The woman’s husband has left her, she has the responsibility of two children, she earns her living by working as a daily wage labourer.

June 20, 2025: On Sunday, A Dalit teenager who dared to ask for ration was shot dead in broad daylight in Bilhari village in Chhatarpur district of Madhya Pradesh. His brother, Ashish, who had accompanied him, was also injured.

June 22, 2025: The incident occurred in Dadrapur village, within the limits of Bakewar Police Station, where a group of Brahmin men attacked a Katha Vachak (religious preacher) and his aides for organising Baagavat Katha in the village after discovering that he belongs to a lower caste.”

June 22, 2025: A 13-year-old patient from Meerut admitted to the orthopaedics ward at a top hospital in the city, was allegedly sexually assaulted by a 20-year-old man inside the women’s washroom around 1 am on Sunday. The girl, a Dalit, was being treated for knock knees, and was accompanied by her mother at the facility’s general ward.

June 22, 2025: At a hospital in an Andhra Pradesh district, a 15-year-old girl, almost eight months pregnant, spends her days in a 150-bed ward, surrounded by expectant mothers and wailing infants. Authorities have deemed it dangerous to terminate her pregnancy at this stage, and say sending her home is not an option either – the teenager is the victim of sexual abuse over two years by 14 men, who are from an influential community in the village where the crimes took place.

June 22, 2025: “A shocking incident of caste-based violence has emerged from Etawah district in Uttar Pradesh on Sunday, where members belonging to the Bahujan community were severely assaulted by upper caste men, who brutalised them and forcefully tonsured their hair, urinated on them, for taking part in a religious event.

June 23, 2025: Two Dalit men were allegedly subjected to brutal physical and psychological abuse in Kharigumma village under Dharakote block in Ganjam district.

June 24, 2025: “Dalit assistant professor Dr Ravi has allegedly faced caste discrimination after the principal at SV Veterinary University’s Dairy Technology College in Andhra Pradesh removed the chair from his office, forcing him to work while sitting on the floor. He alleged that he was on leave on Thursday, and when he returned to the college on Friday and went to his room, he found that there was no chair. Associate Dean Ravindra Reddy, who had come to test the milk in the existing device, had removed the chair from his room.”

June 26, 2025: Nearly All Students Withdrawn from Karnataka School After Dalit Woman Appointed Head Cook. “In a shocking incident from Karnataka’s Uttara Kannada district, a 60-year-old differently abled Dalit woman was allegedly raped and robbed by a known history sheeter. The accused, identified as 23-year-old Fairoz Yasin Yaragatti, was later shot in the leg by police during an encounter”

June 27, 2025: On Friday, members of the family were sowing seeds in their land in Narayanapura village of Madhya Pradesh’s Lateri tehsil when some people, allegedly from the Gurjar community, attacked them. The men not only beat up members of the family, including two women, but also snatched their soybean seeds and sowed them in their own field.

Jyoti D. Bhosale, in The Intensification of the Caste Divide: Increasing Violence on the Dalits in Neoliberal India, [emphasis ours] writes, “The increased physical infliction of violence on the Dalits, apart from simply being the perception of threat, is a reactionary response to prevailing psyche steeped in prejudice and caste arrogance and are expressions of retention of privileged positions within the caste order, in spite of long drawn resistance and constitutional efforts against the same. In their study of Bhumihars (landowning caste) and caste violence in Bihar, Nandan and Santosh (2019) argue that in the context of the crumbling down of traditional mode of dominance through upper-caste identity and feudal agrarian structure, and also with the increased representation of OBCs and other lower castes, the goalpost of the Bhumihars has shifted. It has now become that of establishing themselves not as perpetrators of violence but as guardians of Hindutva which also protects their caste identity. They thus resort to ‘symbolic’ violence towards the lower castes, while on the ‘enemies’ of Hindu right-wing ideology, overt violence is inflicted. Can the quantitative reduction of incidents of bodily violence itself account for decreased brutality against the Dalits? Numerous incidents of violence such as Tsundur massacre (1991); Bara massacre (1992); Bathani Tola massacre (1996); Melavalavu violence (1997); Laxmanpur Bathe massacre (1997); Ramabai Killings(1997); Bhungar Khera incident (1999); Kambalapalli violence (2000); Khairlanji massacre (2006); gangrape of Sumanbalai (2009); Mirchpur killings (2010); Dharmapuri violence (2012); Marakkanam violence (2013); Dangawas violence (2015); Ariyalur gangrape (2016); Kanchanatham temple violence (2018); Hathras gangrape and murder (2020) are amongst the very many clear cases of explicit brutality. These challenge the underlying liberal presumption prevalent across social sciences that with progression in time, democratization etc, societies become more civil. There is evidence to say that with such progression, cruelty may not just continue but also sharpen (Rushe and Kirchheimer 2003).

Thus, it will not be erroneous to state that these enactments of violence are located at the juncture of asserting caste-pride, and the violent need to humiliate and assert dominance through forms that adapt and reinvent themselves with the passage of time.

Sexual Violence

Amidst the different forms of violence enacted upon Dalit and Adivasi people, sexual violence happens to be one of the foremost ones.

Sourik Biswas writes for the BBC, “These [Dalit] women, who comprise about 16% of India’s female population, face a “triple burden” of gender bias, caste discrimination and economic deprivation. “The Dalit female belongs to the most oppressed group in the world,” says Dr Suraj Yengde, author of Caste Matters. “She is a victim of the cultures, structures and institutions of oppression, both externally and internally. This manifests in perpetual violence against Dalit women.” Out of the 113 incidents recorded by CJP, 29 were acts of sexual violence. Approximately 10 rape cases are reported every day when it comes to Dalit women.

Manisha Mashaal, the founder of Swabhiman Society, told Equality Now that one of the biggest challenges in cases of sexual violence is that survivors or the families are pressured into compromises with the accused. Community and social pressure plays a major role in impeding access to justice in such cases. Another issue is the lack of quality and effective systems in place to provide the survivors of violence and their families with immediate social, legal, and mental health support along with proper and timely rehabilitation. This pattern of violence also translates to Adivasi women – even intensifying, with the stereotyping of these women as “promiscuous” and an allotted sexual availability – which ultimately reduces them to fetishized commodities. While Behanbox, upon perusal of a report ‘Beyond Rape: Examining The Systemic Oppression Leading To Sexual Violence Against Adivasi Women’ – found that while the two-finger test that checks the hymen and its rupturing has been outlawed by the Supreme Court, in almost 15 of the 32 cases studied had the victims go through them.

It found that according to the National Crime Bureau Report (2022), a total of 10,064 cases were registered for crimes against Scheduled Tribes (STs), an increase of 14.3 per cent over 2021 (8,802 cases). The crime rate increased from 8.4 per cent in 2021 to 9.6 per cent in 2022. The report reveals that 1,347 cases of rape and 1022 cases of assault on Adivasi/Tribal women were reported in 2022.

Mapping Caste Atrocities and Socio-Political Dynamics

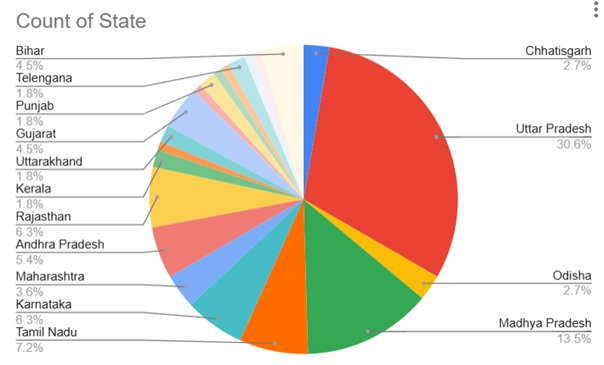

The 113 cases that CJP documented were spread out all over the country– which you can see in this map– although some states emerged as hotspots.

Percentage of Caste Atrocities in Relation to States

As displayed above, the worst offending states were Uttar Pradesh (34 cases), Madhya Pradesh (15), and Tamil Nadu (8). This calculation tracks with NCRB data that the Deccan Herald reported, “About 97.7 per cent of all cases of atrocities against SCs in 2022 were reported from 13 states, with Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh recording the highest number of such crimes, according to a new government report … Of 51,656 cases registered under the law for Scheduled Castes (SCs) in 2022, Uttar Pradesh accounted for 23.78 per cent of the total cases with 12,287, followed by Rajasthan at 8,651 (16.75 per cent) and Madhya Pradesh at 7,732 (14.97 per cent).”

This intensity of caste-based violence in states is deeply reflective of the social structures present within these states and their respective hierarchies.

In Uttar Pradesh, the last caste census was conducted in 1931. According to the data from this census, it was found that only 9.2% of the population was composed of Brahmins, while 7.2% was made up of Rajputs (Thakurs). Sudhir Hindwan’s CASTE AND CLASS VIOLENCE IN THE INDIAN STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH – the intermediary (backward) castes made up about 42 per cent of the population, the scheduled castes 21 per cent and Muslims 15 per cent. While no caste census details are available after that, estimations based on the data from the 2011 census leads us to believe that the 20% of the “forward caste” demographic are composed by the 12% of the populace who are Brahmins, and the remaining 8 the Rajputs.

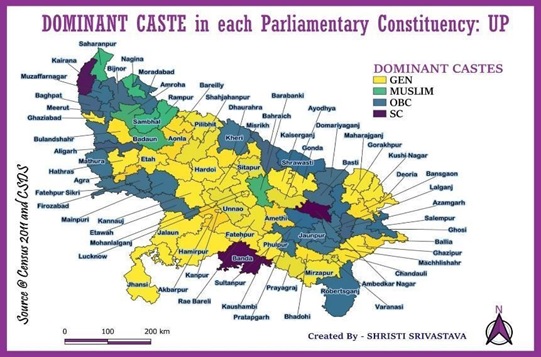

Dominant Caste in each Parliamentary Constituency: UP (Source: Policy Lab, Jindal)

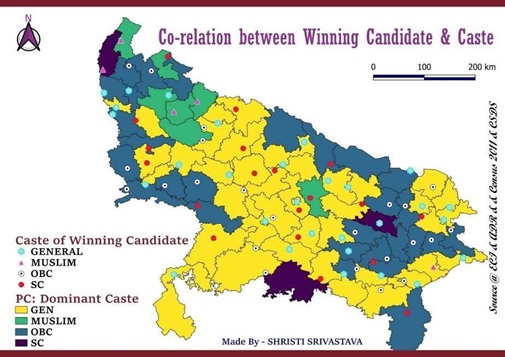

Correlation between Winning Candidate and Caste

A report from the policy research lab of Jindal Global University found that out of the 80 constituencies in the state, 23 of the dominant general caste constituencies have representatives from the respective castes, thus indicating a 100% rate of correlation when it comes to caste identity and election of representation. The report states, “Whereas there were 15 constituencies who have OBC as their dominant caste and their MP too comes from the OBC. On the other hand, there are 3 constituencies where Muslims are dominant, and the winning candidate too comes from the same … Out of the 19 winning candidates who won the 2024 parliamentary elections and come from the scheduled caste background, 17 came from those seats which were reserved for the scheduled caste in the elections, thus out of 80 there were only 2 seats where the winning candidate was from the scheduled caste and the seat was not reserved. This highlights the social disparity that persists within the political and social realm of UP.” The maps pictured here represent this disparity when it comes to the distribution of political power among different caste compositions in Uttar Pradesh.

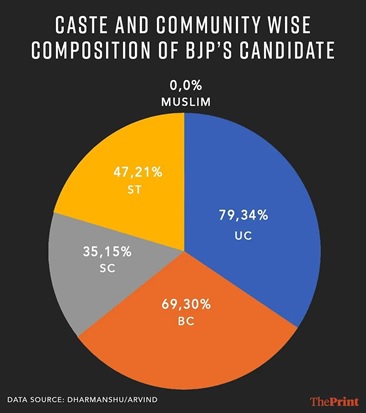

Madhya Pradesh reflects a similar vein of absences. For the 2023 state legislative elections, The Print found on a fieldwork based investigation that the now-ruling party of the state, BJP, had given 34% (79) of its tickets to upper caste candidates, followed by 30% to Backward Classes (69) — while only providing the Scheduled Tribe and the Scheduled Caste candidates 21% (47) and 15% (35) of its tickets — despite being the state with the largest number of tribes. It is also to be remembered that none of these tickets were given to candidates in unreserved constituencies.

Caste and Community Wise Composition of BJP’s Candidature for 2023 legislative elections (Source: ThePrint)

This preference given to the provision of tickets to non-Dalit candidates translated in the poll results. The Hindu reported, “Despite its rhetoric over the question of caste census, Congress failed to make a dent in the OBC vote. Thus, BJP’s landslide victory was shaped by an accretion from most social sections, including the OBCs of Madhya Pradesh. Besides consolidating among its upper caste voter base, the BJP this time managed to attract more OBCs and Adivasis compared to 2018.

The Congress stayed significantly ahead of the BJP among SC communities, while other parties bagged 16%. The BSP polled 19% of the Jatav votes; with the Congress securing almost half the Jatav votes. Among the tribal voters, the Congress maintained an advantage over the BJP. The vote share was the closest among the Bhil community with a difference of only 4% between the Congress and BJP. The Congress secured half or more of the votes of other tribal communities; while the BJP managed more than a third of the votes. Congress did get overwhelming support among Muslims, though their population in the State is barely 7%—hardly enough to help the Congress make an impact. As mentioned above, with BJP gaining among Upper Castes, the Congress found very thin support among these sections, including the Rajputs, compared to 2018. In conclusion, it is clear that the BJP has consolidated its traditional upper caste vote bank, along with making significant inroads into the OBC communities in Madhya Pradesh. The Congress’s vote among the SC, ST and minority communities is not large enough to match the BJP’s social bloc.”

Tamil Nadu: Exceptional Violence

Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, has been known for fostering caste-consciousness from time immemorial. The private sphere is an example – where the National Family Health Survey data suggested that the state had one of the lowest rates of inter-caste marriages, only reaching a meagre 2.59%. The state also has the highest number of consanguineous marriages, with a whopping 28% share, as opposed to the national average of 11%. In a report on caste-based tensions in two villages in Tirunelveli, ThePrint reported, “Students wear coloured T-shirts inside their school uniform, which also refer to their caste identity. Sometimes, those T-shirts will also have the image of leaders of their communities,” said the headmaster of a government school in Madurai, who did not wish to be named … “In the village, we reside in Dalit colonies and they reside in the Upper Caste streets. So, once we get into the school, this segregation remains the same; they don’t sit next to us or mingle with us,” said a Class 10 student of a state-run school in Tirunelveli district.”

As the state gears up for the 2026 elections, one sees the carrying over of trends from 2024 Lok Sabha elections, as the BJP tries to shed its image as a Brahminical party in the state, and makes alliances and coalitions with smaller caste-based parties for greater parties. South First reports, “Tamil Nadu’s ruling DMK, despite its anti-caste image, continues to partner with the KMDK, a regional ally whose leaders have made inflammatory caste-based remarks. The DMK’s support for KMDK-led cultural events, such as Valli Kummi performances, is seen as a move to win over the influential Kongu Vellalar Gounder community. Critics say the alliance highlights a growing ideological dissonance, where electoral calculus increasingly trumps the party’s professed commitment to social justice.” Many political theorists, like TN Raghu, have pointed out that the DMK and the AIADMK are two sides of the same coin – where they have alienated their rooting in Periyar’s anti-caste politics for vote banking strategies. Raghu told SF, “Whether in power or not, DMK has never really raised its voice against the dominant castes. Take for instance the honour killing of Sankar and the struggles of Kausalya – DMK never staged major protests or spearheaded movements around such incidents. They fear that aggressively opposing caste oppression will alienate majority caste voters. Often this silence is justified as political strategy … In elections, it is almost like a competition between DMK and AIADMK – who can stay more silent about caste issues and thereby win more votes from caste-dominant Hindu communities.”

Law Enforcement Failures

While most of these cases have never had any political leadership comment anything reformist, or acknowledge the depth of the rot in each state – the police have been equally responsible in lackadaisical delivery of judgement, if not perpetrating the very same violence in themselves. Out of the 113 cases calibrated by CJP when it comes to anti-Dalit atrocities, 9 were cases where the police directly were violent towards the victims, 6 were cases where no action was undertaken, and 5 were cases where it was unclear if a report was filed. Out of the remaining 92 cases where action was undertaken – there were 4 cases where the action undertaken was merely conducive to procedure and not actual ensuring of justice.

This tracks with NCRB data, which states that 12,159 cases of atrocities against STs were pending investigation, and a total of 2,63,512 cases of atrocities against Scheduled Castes (SCs) while 42,512 cases of atrocities against STs went for trial. Conviction percentage under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 in conjunction with the Indian Penal Code (IPC) remained at 36 per cent for SCs and 28.1 per cent for STs. At the end of the year, 96 per cent of cases of atrocities against SCs were pending trial whereas, for STs, the percentage stood at 95.49.

GC Pal, in Caste and Consequences: Looking through the Lens of Violence, writes, “As caste relations are rooted in the social structure, caste traditions and the advent of modernity together produce a new ‘coalition’ between dominant caste perpetrators and the classes (powerful members from their caste groups in community and also from administration). The social status of the accused and its association with larger ‘social class’ plays a significant role in course of access to justice. Overwhelming caste loyalties and sentiments influence the decisions of the personnel in administration and judiciary. Moreover, the administration being represented majorly by the dominant caste members very often show apathy towards the complaints. In this regard, Ambedkar (1989) is of the view that: ‘When law enforcement agency- the police and the judiciary, does not seem to be free from caste prejudice- since they are very much part of the same caste ridden society- expecting law to ensure justice to victims of caste crimes is rather an impractical solution to this perennial social problem.’ That is why, he emphasises that the presence of elaborate legal provisions may not always guarantee rights to social justice, it necessarily depends upon the nature and character of the civil services who administer the principle…‘If the civil services, by reason of its class bias, is in favour of the established social order in which the principle of equality had no place, the new order in the form of equal justice can never come into being’ (ibid)”

Conclusion

This report details the deep rot within the Indian socio-polity, and its exacerbation by the current Hindutva machinery, ideologically driven with accompanying violence against targeted sections as a key tool for penetration. Dalits are one such target.

The way forward, would perhaps be rooting policy action in accountability and welfare, then just vote bank strategy. Over the years, multiple judicial decisions have weakened the PoA, with judgements refusing to grant caste slurs “prima facie value” – when not made in “public view”.

According to Equality Now, the NCWL’s recommendations to India’s Central Government and State Governments outline steps duty-bearers should take to protect Dalit women and girls from sexual violence, and ensure justice and protection:

- Incorporate and effectively implement the abolition of caste-based discrimination and patriarchy in national-level law and policy;

- Recognise Dalit women as a distinct social group; develop and implement policies specifically focused on advancing their rights, wellbeing, equal standing, and protection within the law;

- Produce and disseminate disaggregated data on the status of Dalit women, particularly in government plans and development programmes; address intersectional forms of discrimination throughout the criminal justice system;

- Ensure full and strict implementation of existing legal protections, particularly the Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, and the timely investigation and disposal of cases of violence against Dalit women and girls;

- Organise, support and fund community-based education, legal literacy and training programmes that improve understanding of intersectional discrimination and violence, including combating casteist and sexist stereotypes amongst criminal justice system officials; empower Dalit communities to better understand their legal and constitutional rights;

- Recognise that economic dependence is a significant reason behind Dalit women not filing police complaints; deliver a national plan with separate funding aimed at accelerating efforts to reduce the poverty gap between Dalit communities and the general population;

- Ensure Dalit survivors who report sexual violence are legally protected by the state from retaliation by the accused; prevent further violence targeting them, such as through social boycotts, and impose restrictions on these;

- Provide Dalit survivors and family members with immediate and longer-term assistance including medical aid, free legal aid, psycho-social support services and counselling, and quality, holistic rehabilitation.

Key to these systemic changes is acknowledgement of the deep-rootedness of the problem. Indian society and politics, resistant and rigid against such self-scrutiny when it comes to caste bias and communalism, has remained obdurate in its inability internalise this malaise. Until that happens, any measures taken to address the issue could remain palliative.

(The legal research team of CJP consists of lawyers and interns; this graphic visualisation report has been worked on by Saptaparma Samajdar)

[1] From Human Rights Watch’s pathbreaking 1999 Report, Broken People. These quotations are from: 1 Human Rights Watch interview, Ahmedabad district, Gujarat, July 23, 1998. See explanation of manual scavenging below in the Summary and in Chapter VII. 2 Human Rights Watch interview, Madurai district, Tamil Nadu, February 17, 1998. 3 Human Rights Watch interview, Madurai city, Tamil Nadu, February 18, 1998. https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/india/India994-02.htm#P350_19723

[2] “Dalit” is a term first coined by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, one of the architects of the Indian constitution of 1950 and revered leader of the Dalit movement. It was taken up in the 1970s by the Dalit Panther Movement, which organized to claim rights for “untouchables,” and is now commonly used by rights activists.

[3] https://www.amazon.in/Adivasi-Vanvasi-Tribal-Politics-Hindutva/dp/0143470485 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09731849241260929;

[4] A Committee set up by the Ministry of Human Resource Development and headed by Avdhash Kaushal reported on Ekal Vidyalaya schools in the Singhbhum district in Jharkhand and in the Tinsukia and Dibrugarh districts in Assam. The Committee’s report, submitted to the MHRD in 2005, brings out the communalisation that is rampant in these schools and in their curriculum and textual materialsThe teacher at the Ekal Vidyalaya in Chirchi in Tantnagar block, Singhbhum district, proudly claimed that rather than imparting alphabetical knowledge, he was more intent on protecting “Hindu culture”. He also boasted of his role along with other colleagues in the illegal destruction of a half-built church in the village in 2002. The report states: “The training to the teachers of Ekal schools was mainly to spread communal disharmony in the communities and also to inculcate a fundamentalist political ideology… creating enmity amongst communities on the basis of religion.” The complete report, ‘Final Report on the field visit and observations of Mr Avdhash Kaushal for Singhbhum district in Jharkhand and Tinsukia and Dibrugarh districts in Assam’, can be accessed at: http://www.sabrang.com/khoj/ekal_report.pdf

[5] MS Golwalkar, the chief ideologue of the RSS had espoused in We or Our Nationhood Defined, “…only those movements are true ‘National’ that aims at re-building, re-vitalising and emancipating from its present stupor, the Hindu Nation. Those only are nationalist patriots, who, with the aspiration to glorify the Hindu race and Nation next to their heart, are prompted into activity and strive to achieve that goal. All others are eithertraitors and enemies to the National cause, or, to take a charitable view, idiots…outsiders, bound by all the codes and conventions of the Nation, at the sufferance of the Nation and deserving of no special protection, far less any privilege or rights. There are only two courses open to the foreign elements (Christians and Muslims), either to merge themselves in the national race and adopt its culture or to live at its mercy so long as the national race may allow them to do so and to quit the country at the sweet will of the national race. That is the only sound view on the minorities’ problem’; https://sabrangindia.in/document/we-or-our-nationhood-defined-1947-edition/