The Conspiracy of Silence: HC denies bail to Delhi riots accused Five years of pre-trial incarceration reveal how FIR 59 turns suspicion into proof and the UAPA transforms dissent into terrorism

18, Sep 2025 | CJP Team

“If there is no sound

How can I break through

This heavy silence layering my mind?

Without the sound of words

How do I light the vision

Hidden these long days in my eyes?

I must speak and listen to my people

and learn my words again—

If a man loses words

What is left?”

– Varavara Rao, ‘The Word is the World’ (Captive Imagination)

‘Political Prisoner’ is the criminal offense which most brazenly betrays the promises of a democratic state. It is not a crime of actions but of words: of thinking, speaking, reporting, questioning, demanding, dissenting, resisting. The incarceration of political prisoners strips away the spectacle of electoral politics and constitutional ornaments, exposing the State’s primal instinct: to smother the truth spoken to power, subjugate through enforced silence, and sanctify fear as the law.

On September 2, 2025, the Delhi High Court passed two orders denying bail to ten political prisoners accused in the ‘Delhi Riots Conspiracy Case.’ Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Athar Khan, Abdul Khalid Saifi, Mohd Saleem Khan, Shifa-ur-Rehman, Meeran Haider, Gulfisha Fatima, Sabad Ahmed, and Tasleem Ahmed were imprisoned in 2020 under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA). Five years later, not a single charge has been framed against them and the trial is far from beginning. The law’s silence is the verdict.

How does a democratic state produce a justice of silence? To answer that, we must unearth the making of a conspiracy: how an investigator’s opinion becomes evidence, the prosecutor’s narrative becomes statutorily irrefutable, and the court’s seal turns lie into truth. We ask what it means to be named a terrorist, expose the perversion of bail under the UAPA, and examine what allows a court to flout judicial precedent and abandon constitutional promises. Will the law emerge as a tool of the people’s justice or a farcical ceremony to justify the oppression of a proto-fascist state?

Engineering a Pogrom

On December 11, 2019, the Indian Parliament led by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) passed the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), which provided an accelerated pathway to Indian citizenship for persecuted refugees of Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian faith. Read alongside the country-wide implementation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), the act entrenches a religious basis for citizenship where Indian Muslims, particularly the poor who often lack documentation to ‘prove’ their citizenship, face the prospect of statelessness. This exclusionary design directly flows from the ideology of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the parent body of the BJP, which believes that Muslims, or followers of any religion whose holy sites are located outside of India, can never be equal citizens.

The mass movement against the CAA-NRC was the first major popular challenge to the BJP since it came to power in 2014. What began as student rallies on college campuses evolved into peaceful sit-ins and road blockades (chakka jams) led by women residents, transforming ordinary neighbourhoods into vibrant sites of democratic assertion. It was the first time in the history of independent India that Muslims, under a young, diverse, and committed leadership, came out on the streets not just as a minority community but as proud citizens. It was a deeply instructive moment for young people to learn about politics, organisation, and the power of collective action. By January 2020, there were around 40 sit-ins across the country, with 10 in New Delhi, where people would stage a tent (pandal), host speeches and raise slogans against the discriminatory law. The largest of such sit-ins was in Shaheen Bagh.[1]

“The path shown by Shaheen Bagh has made our country into one big baagh (garden), and we will bring spring in this garden.” – Umar Khalid (Speech at Amravati, February 2020)

Timeline of Events

Given that the anti-CAA movement was directed at the government to repeal the law and there was no real cause for conflict between Hindus and Muslims, the BJP had to work hard to whip up public sentiment against it. In an apparent bid to polarise the public before the Delhi state elections (that were to be held on February 8, 2020), right-wing activists played up the fact that the anti-CAA protesters were blocking roads and inconveniencing daily commuters.[2]

On January 27, BJP MP Anurag Thakur, while campaigning in North West Delhi, raised the slogan “desh ke gaddaron ko,” to which the crowd roared “goli maaro sallon ko” (‘shoot down the bastards who betray the country’).

On January 28, BJP MP Parvesh Sahib Singh Verma vowed that If the BJP comes to power in Delhi, they would clear Shaheen Bagh within an hour. “Lakhs of people gather there (Shaheen Bagh)… They will enter your houses, rape your sisters and daughters, kill them,” he claimed in a televised interview.

On the same day, JNU PhD student Sharjeel Imam was arrested by the Jehanabad police and booked under multiple FIRs.

On February 11, the BJP lost the Delhi elections.

On February 20, the Supreme Court set up a mediation team headed by Senior Advocate Sanjay Hegde and Sadhna Ramachandran to hold talks with the protestors at Shaheen Bagh. This was the first attempt to reach out to those who had been sitting in protest since December 16.

However, the government continued to respond to the demands with absolute indifference with no Central Minister deigning to engage with the protesters. With the talks going nowhere, protesters targeted US President Donald Trump’s visit to India on February 24 and 25 to draw attention to themselves by blocking roads.

On February 23, senior BJP leader Kapil Mishra called for forcefully removing protestors. Speaking at Jaffrabad, North East Delhi, Mishra told his supporters, “We will be peaceful till Trump leaves. But after 3 days, if the roads are not cleared, we will not listen to the police.”

Kapil Mishra speaking at Maujpur, North East Delhi, flanked by Deputy Police Commissioner Ved Prakash Surya in riot gear

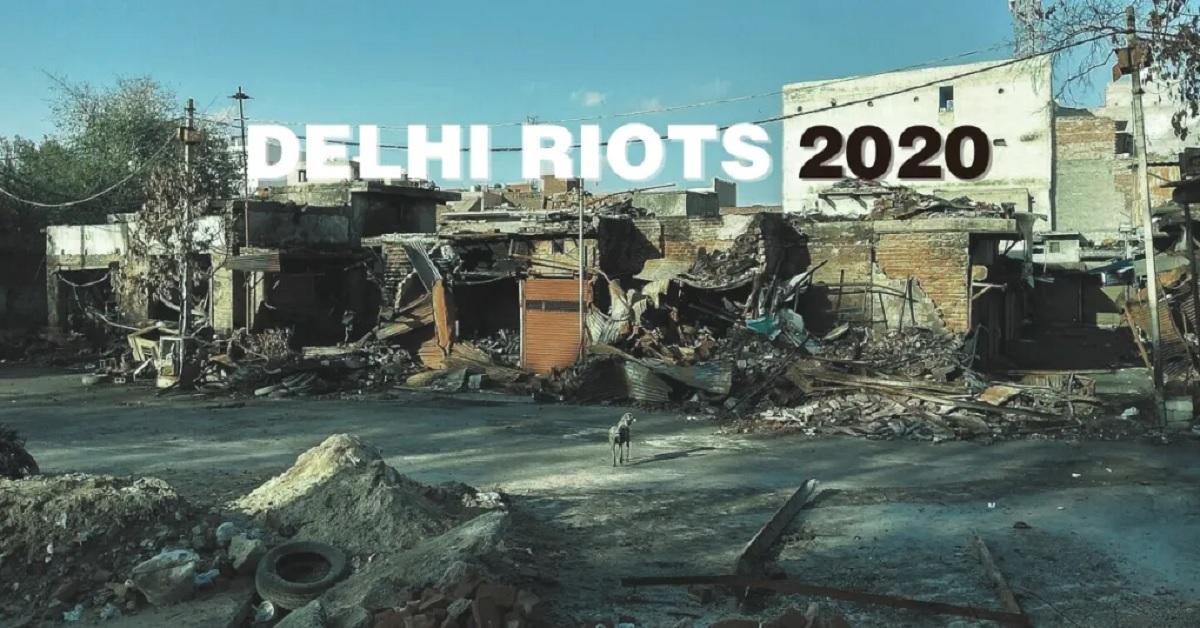

Hours later, violence erupted in North-East Delhi. The riots went on for five days, leaving 53 people dead, 38 Muslims and 15 Hindus, and 700 injured (for the sake of brevity, we will not go into detail about the violence. Fact-finding reports by the Delhi Minorities Commission (DMC) and Amnesty International India can be read here and here).

On February 25, BJP MLA Abhay Verma led a procession in East Delhi, chanting ‘Jo Hindu hit ki baat karega, wohi desh pe raj karega’ (Only the one who talks of Hindu interests will rule the country), among other provocative slogans.

Of the numerous incidents of hate speech by BJP leaders in the lead up to the riots, the aforementioned four were played in open court on February 26, at the direction of then-Justice S. Muralidhar of the Delhi High Court. The furious judge condemned the hate speeches, questioned the complicity of the police, and instructed the State to ensure the safety of riot victims. That night, Justice Muralidhar was transferred to the Punjab and Haryana High Court, and the case was handed over to a new bench.

On the same day, former municipal councillor Ishrat Jahan and United Against Hate co-founder Abdul Khalid Saifi were arrested by the Jagatpuri police.

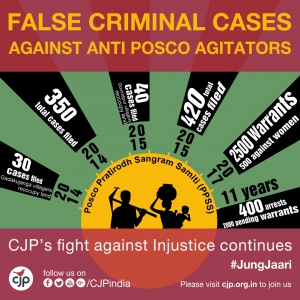

On March 6, sub-inspector Arvind Kumar of the Delhi Crime Branch filed the chargesheet for FIR 59/2020, which claimed that the Delhi riots were the result of a “pre-planned conspiracy” by anti-CAA protestors. The accused were charged under 26 sections of the Indian Penal Code, including for murder, sedition, criminal conspiracy, and promoting communal enmity, two sections of the Arms Act, and four sections of the UAPA.

By March 24, the nationwide lockdown to curb the COVID-19 pandemic brought the movement at Shaheen Bagh and other sites to an abrupt halt.

FIR 59: Manufacturing the Narrative

Criminal procedure requires that upon receiving a complaint that prima facie constitutes a cognisable offence, the police must register an FIR. However, the DMC’s fact-finding report reveals that several complaints by Muslim victims were either not registered, delayed indefinitely, or not acted on. In some cases, the police refused to register an FIR unless the complainant omitted names of the accused. In others, victims were asked to arrive at a “compromise” with the accused and withdraw their complaints. On occasion, victims who went to file complaints were themselves arrested.

Of the chargesheets that were filed, crucial aspects of the chain of events, such as Kapil Mishra’s speech, were glaringly absent. The report observes how the investigations were “purposefully misdirected” to twist the cause of the violence: “the entire narrative has been changed to one of violence on both sides rather than a pogrom that was in fact carried out.”

From the outset, the investigation did not seek to reconstruct events to establish accountability for the violence. Instead, the chargesheets wove a narrative designed to legitimise a pre-determined story, where victims were culprits and aggressors were bystanders. This narrative was crystallised by FIR 59, the omnibus “conspiracy” case which charges the accused as “masterminds” of a “premeditated” plot to escalate road blockades into violent communal riots and “defame India” during the US President’s visit.

The charge sheet states that the riots began when “Muslims living in Chand Bagh and New and Old Mustafabad areas were mobilised… in order to precipitate a violent ‘Chakka Jaam’, which led to brutalisation intimidation and inflicting deadly injuries on police personnel and non-Muslim communities,’’ alleging that the “other community” (Hindus) only “retaliated” in self-defence.

The initial chargesheet, filed in Court on September 16, 2020, names 15 accused:

- Abdul Khalid Saifi

- Ishrat Jahan

- Meeran Haider

- Tahir Hussain

- Gulfisha Fatima

- Safoora Zargar

- Shafa-ur-Rahman

- Asif Iqbal Tanha

- Natasha Narwal

- Devangana Kalita

- Shadab Ahmed

- Salim Malik

- Salim Khan

- Athar Khan

- Taslim Ahmad

The Supplementary chargesheet, filed on November 22, 2020, names 3 additional accused:

- Umar Khalid

- Sharjeel Imam

- Faizan Khan

An essential ingredient of a criminal conspiracy is a ‘meeting of minds,’ i.e., a common intent in furtherance of an unlawful goal. To demonstrate this, the chargesheet devotes significant attention to a WhatsApp group called ‘Delhi Protest Solidarity Group’ (DPSG). Student activists are branded “hardcore, professional ideological deviants,” and their routine discussions about protest organisation presented as evidence of complicity. However, the police’s submission contradicts its own story: a message shared at 5:38 PM on February 23 reads “Pro-CAA protesters are pelting stones at the locals and anti-CAA protesters in the Maujpur area,” followed by video evidence. Subsequent messages show activists scrambling to respond to violence already underway.

The chargesheet is riddled with such selective omissions and factual absurdities. The police allege that Tahir Hussain met the “intellectual architect” Umar Khalid on January 8 and plotted communal riots to coincide with Trump’s visit – an impossible timeline, since the visit was not publicly announced until January 13. The chargesheet has since quietly dropped this claim.

The police further claim that the feminist activist group Pinjra Tod provided “a tactical female shield” to the protests, placing women at the forefront to “deter police” from taking action. This is a terribly misogynistic charge, which assumes that women can only be ornamental pawns without agency. Of the hundreds of women deposed, the chargesheet cannot provide a single statement suggesting she was procured, paid, or made “cannon fodder” at a protest site. It is a gross insult to the dadis of Shaheen Bagh, who sustained the peaceful sit-in throughout the five days of rioting.

The 17000-page chargesheet could not attribute a single act of violence, recovery of weapons, speech resulting in incitement, or call for violence to the named accused. The “principal mastermind” Umar Khalid was not even present in Delhi in the three days of the violence. Numerous speeches have quoted him paying homage to the Indian Constitution, and the values of the non-violent struggle led by Mahatma Gandhi. The investigative narrative, built on omissions, inversions, and conjecture, effectively recast democratic protest into terrorism.

Citizen or Terrorist? Designation as Condemnation

The clandestine nature of a conspiracy made it the perfect storytelling weapon: elastic enough to sustain allegations without showing any causal connection between the accused and the crime, and wide enough to drag just about anyone within its ambit. Once a citizen is designated a “terrorist” who poses a “threat to national security,” facts, evidence, and constitutional reasoning are drowned under conspiratorial hysteria. The absurd reach of this logic is captured by the case of Faizan Khan, a mobile-seller whose crime was selling a SIM card to Jamia student Asif Tanha, which the police claim was later used to ‘plan the conspiracy and the violence.’ For selling a SIM card, Khan was charged with committing a terrorist act.

The UAPA designation was not incidental either. The initial FIR against Umar Khalid’s speeches did not even contain non-bailable offences – these were added only after the Magistrate granted bail to the first set of arrested accused. By then, more than 750 FIRs had already been registered for separate incidents of violence and property destruction[3]. However, even if the accused are acquitted or allowed bail on other charges, they continue to remain incarcerated under FIR 59.

The invocation of the UAPA enables the prosecution to sidestep ordinary bail safeguards and prolong pre-trial detention. Under the Code of Criminal Procedure, the police have 90 days to complete an investigation and file a chargesheet. The UAPA doubles this period to 180 days, allowing the police to stagger arrests over several months, endlessly revise their case, and keep the accused imprisoned while the narrative takes root.

Significantly, Section 43D(5) of the UAPA flips the maxim ‘bail is the rule, jail is the exception’ over its head. The provision states that if the Court, after perusing the case diary and the chargesheet, finds reasonable grounds for believing that the accusation is prima facie true, then the accused cannot be released on bail. Notably, at this stage, the defence can neither submit exculpatory evidence nor cross-examine the prosecution’s case.

In NIA v Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali (2019), the Supreme Court interpreted “prima facie true” to mean that the materials or evidence in the FIR “must prevail until contradicted” and the Court is to record a finding based on “broad probabilities.” The Court held that:

- At the stage of bail, courts cannot examine “the merits and demerits” of the evidence or discard any material collated by the investigating agency as inadmissible

- The evidence must be considered “in its entirety” and “not by analysing individual pieces of evidence or circumstance”

Taken together, this means that courts are not only permitted but effectively required to swallow the prosecution’s story whole, while being explicitly forbidden from testing the truth or admissibility of the individual facts on which it rests. Section 43D(5) precludes judges from granting bail if even a “prima facie” case is made out, and Watali lowers the degree of satisfaction to ensure that the prima facie case is made out. The judgement is widely and often blindly cited by High Courts in several bail rejection orders, rendering judicial discretion subservient to the suspicions of the investigating officer.

Though Watali has cast a long shadow, not all subsequent courts have spoken in one voice. A line of liberty-affirming rulings by the Supreme Court has pushed back against its carceral logic. These trace all the way back to Shaheen Welfare Association v. Union of India (1996), where the Court acknowledged the legislature’s decision to sacrifice some personal liberty for the sake of protecting the community, but stipulated that this very sacrifice makes it “all the more necessary that investigation of such crimes is done efficiently” to ensure that “persons ultimately found innocent are not unnecessarily kept in jail for long periods.”

Within modern jurisprudence, the most significant post-Watali judgments are:

- Union of India v K.A. Najeeb (2021) recognised that protracted incarceration violates the Constitutional right to a speedy trial under Article 21. The Court held that:

- Section 43D(5) is not the sole metric, but merely ”another possible ground” for the Court to deny bail.

- The rigours of a provision like Section 43D(5) will “melt down where there is no likelihood of trial being completed within a reasonable time and the period of incarceration already undergone has exceeded a substantial part of the prescribed sentence.”

- Thwaha Fasal v Union of India (2021) observed that there must be an element of “mens rea” discernible from the facts and circumstances to constitute an offence under the UAPA. The Court ruled that:

- The chargesheet must demonstrate some “overt act” from which it is reasonable to infer that the accused intended to further terrorist activities of a proscribed organisation.

- In other words, vague allegations of conspiracy, based on the general behaviour of the accused, or of the materials that might have been recovered from them, is not enough; there must be a prima facie existence of intention to commit an actual terrorist act.

- Vernon v State of Maharashtra (2023) granted bail to two accused in the Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case on the ground that the prosecution’s evidence was of “weak probative quality.” The ruling affirmed that:

- Courts must engage in (at least) a surface analysis of probative value of the evidence, as a prima facie case cannot reasonably be made out on weak or unbelievable evidence

- When statutes have stringent provisions, there is a greater obligation on the Court to ensure swift adjudication: “graver the offence, greater should be the care taken to see that the offence would fall within the four corners of the Act.”

- Shoma Kanti Sen v State of Maharashtra (2024) granted bail to 66-year old Shoma Sen, accused in the Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case, who had been in detention for six years without the charges being framed. The Court highlighted that even the bail-restricting provision of Section 43D(5) must “bow before the right to bail” after prolonged incarceration:

- Bail is a “fundamental right” under Article 21. Courts must consider whether the deprival of liberty from pre-trial detention, both at investigation and post-chargesheet stage, is justified as “reasonable,” “proportionate,” and “following a just and fair procedure.”

- When considering the evidence prima-facie, the court noted that most of the materials from recovered from third parties, that the prosecution has not been able to “raise a hint of corroboration” to accusations of terror financing, and that there is no connection has been established to show a link to a banned organisation.

Because of this split jurisprudence, UAPA bail hearings have become intense sites of contestation between a jurisprudence of carcerality and a jurisprudence of liberty. The pattern of hearings in the Delhi Riots and similar conspiracy cases reveals that courts are faced with a choice: to either fill the gaps in the prosecution’s case with inferences and speculation to make out a prima facie case, or to insist on corroboration and refuse to substitute assumptions for individualised, factual, and particularistic allegations.

It is damning enough that liberty has been reduced to a gamble; worse still is the realisation that even this gamble is rigged with insidious, extra-legal interventions — as the saga of Asif Iqbal Tanha, Natasha Narwal, and Devangana Kalita will show.

The First Cracks: Bail for Asif, Devangana, and Natasha

On June 15, 2021, Justices Mridul and Bhamban of the Delhi High Court passed three orders granting bail to Asif Iqbal Tanha, Devangana Kalita, and Natasha Narwal. This was the first instance of bail granted on merits in the Delhi Riots cases.

The Delhi High Court began by examining the object and purpose of the UAPA. As a central legislation, it could only have been enacted under the Union’s legislative competence under Article 246 and the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. Therefore, the intent of the UAPA and its amendments “could only have been, to deal with matters of profound impact on the ‘Defence of India’, nothing more and nothing less” (Asif Iqbal Tanha).

This, the Court observes, demonstrates that the stringent provisions of the UAPA are meant to apply only to exceptional cases, and not as a substitute for ordinary criminal law. In distinguishing the ‘exceptional’ from the ‘ordinary,’ the Court relies on Hitendra Vishnu Thakur v State of Maharashtra (1994) to emphasise that the extent of a terrorist activity “travels beyond the effect of an ordinary crime” and “must not arise merely by causing disturbance of law and order or even public order.” These distinctions have been further clarified in Ram Manohar Lohia v State of Bihar (1965), which devised “three concentric circles” to explain the gravity of offences – law and order being the largest, public order being the second, and security of the state being the smallest (gravest).

Having located UAPA within the narrowest circle, the Court turned to the definition of ‘terrorism’. Here, it relied on Maneka Gandhi vs. Union of India (1987) which cautioned that the “life and liberty of the person cannot be put on peril of an ambiguity,” holding that when concepts are inherently imprecise, “courts must strive to give to those concepts a narrower construction than what the literal words suggest.”

Given that UAPA charges are extremely serious with severe punishments, the Court emphasised that the “formation of an independent judicial view” at every step of the way is imperative. It then turned to the prosecution, which carried the investigators’ conspiracy narrative into the courtroom by arguing that what unfolded was not a “typical protest” but an “aggravated protest,” deliberately engineered to disrupt life in the capital. Examining the record, the Court stripped away what it called “superfluous verbiage, hyperbole, and stretched inferences,” and observed that the allegations – inflammatory speeches, organising chakka jams, instigating women to protest, stockpiling materials – are, at worst, evidence of “organised protests” which are “not uncommon when there is widespread opposition to Governmental or Parliamentary actions.” Even if such protests were noisy, disorderly, or crossed the constitutional limits of peaceful assembly, they could only be regulated or prohibited under ordinary law. A protest, even if it spills over into the zone of illegality, is in no way a terrorist act or a conspiracy understood by the UAPA (Natasha Narwal).

“It appears that in its anxiety to suppress dissent and in the morbid fear that matters may get out of hand, the State has blurred the line between the constitutionally guaranteed ‘right to protest’ and ‘terrorist activity’. If such blurring gains traction, democracy would be in peril.” – Delhi High Court (Devangana Kalita v State of Delhi NCT, 2021)

The Court recognised the Supreme Court’s ruling in Watali which bars courts from delving into the “merits or demerits” of evidence at the bail stage. It logically concluded that courts must equally resist from delivering into “suspicions and inferences that the prosecution may seek to draw,” and consider the evidence as-is. This reasoning struck at the heart of the prosecution’s case: the evidence showed that (i) the accused organised a protest and chakka jam and (ii) violence occurred in North Delhi, but there was no material demonstrating a causal link between the two. This gap was being filled by assumption and accusation, with the prosecution arguing that even the “likelihood” that the accused’s acts may threaten the nation are an offence within the meaning of sections 15 and 18 of the UAPA. The Court was thoroughly unconvinced, writing that “the foundations of our nation stand on surer footing than to be likely to be shaken by a protest, however vicious, organised by a tribe of college students.”

Next, the Court noted that the accused had spent over a year in pre-trial custody, with 740 prosecution witnesses yet to depose and the trial far from commencing. Relying on Najeeb, it underscored that Section 43D(5) does not override a Constitutional right. In response to the protests of the prosecution, the Court asked pointedly it should wait till the accused have “languished in prison long enough” till their right to a speedy trial “is fully and completely negated, before it steps in and wakes-up to such violation.” (Asif Iqbal Tanha)

Echoing the standard laid out in Thwaha Fasal, the Court questioned whether there was any specific and overt act linking the accused to a terrorist act or its preparation. It observed that the particular acts directly attributed to the accused are WhatsApp messages showing they organised a chakka-jaam, that Narwal and Kalita as part of Pinjra Tod (a lawful organisation) organised women for sit-ins, and that Tanha handed over a SIM card to a co- accused. In the absence of weapons, explosives, or evidence of incitement to violence, the Court dismissed the accusations finding that they built on “inference” and “grandiloquence” rather than concrete, particularised allegations sufficient to make out offences under Sections 15, 17, or 18 of the UAPA.

The three judgments can be read here.

“Not to be treated as precedent”

The very next day, the State rushed to the Supreme Court, complaining that the Delhi High Court had turned the UAPA “upside down.” On June 18, 2021, the Supreme Court heard the appeal and upheld bail. However, it added an extraordinary caveat: that the High Court’s judgment, including its interpretation of the UAPA, “shall not be treated as a precedent and may not be relied upon in any proceeding.”

Advocate Gautam Bhatia has explained that while the phrase “not to be treated as a precedent” has become a recurring feature in Indian jurisprudence, it is entirely outside the law.[4] When a constitutional court delivers a reasoned judgment, the appellate court’s role is only to decide whether it was right or wrong. Until reversed, that judgment carries the force of law. It is not within the Supreme Court’s authority to act as if the judgment of another constitutional court simply does not exist — and worse, to order every other court to participate in this legal fiction.

The Delhi High Court’s judgment was not reversed but absurdly quarantined. The only possible objective was to ensure that the order could not be binding precedent used to secure bail for any other accused in the Delhi Riots conspiracy case, given the clear factual parity. In the interim order, the Supreme Court explains that “the idea was to protect the State against use of the judgment on enunciation of law qua interpretation of the provisions of the UAPA Act in a bail matter.” The highest court in the land stated unequivocally that it was not concerned with protecting individual liberty against the State, but with protecting the State against individuals seeking liberty[5].

The Supreme Court’s order can be read here:

“All Appeals Dismissed”

Five years after the riots that shook Northeast Delhi, on September 2, 2025 at 2:30 pm, the Division Bench of Justices Naveen Chawla and Shalinder Kaur of the Delhi High Court read out the verdict on the bail applications of Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Athar Khan, Khalid Saifi, Mohd Saleem Khan, Shifa-ur-Rehman, Meeran Haider, Gulfisha Fatima, and Shadab Ahmed. “All appeals are dismissed.”

Another coordinate bench of Justices Subramonium Prasad and Harish Shankar pronounced a separate order denying bail to Tasleem Ahmed.

The first order runs into 133 pages. The judgment begins by canonising the conspiratorial narrative into a statement of facts. The prosecution’s case rested on two evidentiary limbs:

- Testimonies of “protected witnesses” – anonymous individuals who claim to have overheard the accused having secret meetings where they conspired to bring about violent riots

- Circumstantial material – WhatsApp messages, distribution of “inciteful” pamphlets, public speeches calling for bandhs, chakka jam and non-cooperation, a “flurry of phone calls” after the riots

The Court relied on Gurwinder Singh vs State Of Punjab (2024), which held that “mere delay in trial pertaining to grave offences cannot be used as a ground to grant bail.” The ruling encapsulates the eight-point ‘Test for Rejection of Bail’ as laid down by Watali:

- Meaning of “Prima facie true” (On the face of it, the materials must show the complicity)

- Degree of Satisfaction (Lower that ordinary criminal law)

- Reasoning necessary, but no detailed evaluation of evidence

- Record a finding on broad probabilities, not based on proof beyond doubt

- Limitation under Section 43D(5) applies from registration of FIR till conclusion of trial

- Material on record must be analysed as a whole; no piecemeal analysis

- Contents of documents to be presumed as true

- Admissibility of documents relied upon by Prosecution cannot be questioned

The Court then analyses the accused’s roles in four parts, grouping individuals by protest site or broad organisational function. At the outset, this clubbing masks the absence of individualised evidence and allows the High Court to skirt its duty to test whether the allegations against each person were specific and particularised. Inferences are treated as facts, generic circumstances as evidence, and ten people are reduced to shadowy actors with undefined roles in a pre-narratavised conspiracy.

Sharjeel Imam and Umar Khalid

At the time of hearing, Sharjeel had been imprisoned for 2044 days and Umar for 1815 days. This does not seem to perturb the Court in the slightest, which instead zeroes in on the prosecution’s label that the two were the “intellectual architects” behind the alleged conspiracy. Nowhere does the judgment ask what it means to be an “intellectual architect,” or explain how mere membership of WhatsApp groups, distribution of pamphlets in college campuses, and untested testimony about meetings can be stretched into so far as to infer that two Muslim student activists masterminded communal violence in the national capital which resulted in an overwhelming proportion of Muslims being killed. It is worth noting here that Sharjeel had already been in custody since a month before the riots, and Umar had been under 24×7 police protection and electronic surveillance since 2018.

In Paragraphs 132-133, the Court refers to the ‘inflammatory speeches’ given by Sharjeel at Aligarh, Asanol, and Chakand and by Umar at Amravati. Aside from noting that they were ‘preaching to the masses by misleading them into believing that the CAA/NRC is an Anti-Muslim law’ – a political judgement that is utterly irrelevant to the legal question of culpability – the Court offers absolutely no textual or contextual analysis of the speeches. Absent even a surface-level inquiry into how the rhetoric allegedly crossed the threshold from protected speech under Article 19(1)(a) into incitement or terrorist conduct, the Court simply concludes that the role assigned by the prosecution “cannot be lightly brushed aside.”

“We will not respond to violence with violence. We will not respond to hate with hate. If they spread hate, we will respond to it by spreading love. If they beat us with lathis, we will hold aloft the tri-color. If they fire bullets, then we will hold the Constitution and raise our hands. If they jail us, we will go to jail happily singing, ‘Saarey Jahaan Se Acha, Hindustan Hamara.’ But we will not let you destroy our country.” – Umar Khalid (Speech at Amravati, February 2020)

A full transcript of Umar’s speech can be read here.

A portion of Sharjeel Imam’s speech at the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) was broadcast by electronic media channels and shared apparently out of context on social media to portray him as an Islamist pushing a secessionist agenda. The law draws a distinction between discussion, advocacy, and incitement – “Mere discussion or even advocacy of a particular cause howsoever unpopular is at the heart of Article 19(1)(a). It is only when such discussion or advocacy reaches the level of incitement that Article 19(2) kicks in” (Shreya Singhal v Union of India, 2015). There is no evidence to establish a causal link between Sharjeel’s speech and an overt act of violence.

Athar Khan, Shadab Ahmed, Abdul Khalid Saifi, and Mohd Saleem Khan

The State alleged that they were members of “various WhatsApp groups, which facilitated organized coordination of protests,” delivered “provocative speeches on religious lines,” and were present at “various meetings” on the night of February 23. The specific accusations against the four individuals are:

- Athar Khan and Shadab Ahmed: Were “in agreement” to destroy or cover Government-installed CCTV cameras so that they could “operate fearlessly.” This was based on statements by protected witnesses, testimony by police, and membership of the DPSG WhatsApp group.

- Saleem Khan: Dislocated a government CCTV camera with a stick-like object to attack the police and non-Muslims. CCTV footage allegedly showing him disabling a camera.

- Khalid Saifi: Raised funds and procured firearms for the conspiracy through NGO and NRI contacts. This is based on protected witness statements and CDR location data placing him at protests.

At the time of the hearings, Athar Khan had been in custody for 1889 days, Shadab Ahmed for 1976 days, Saleem Khan for 2002 days, and Khalid Saifi for 2016 days. Too many gaps in the prosecution’s case remain unanswered.

- Statements of the Protected witnesses were recorded after a considerable lapse of time from the registration of the FIR, and conveniently filled up the gaps in the prosecution case. The defence contends that these may be planted witnesses. At the stage of bail, their identities are not known to the defence.

- Police witnesses, including Constables and Head Constables, have given almost identical statements across all three FIRs. The defence contends that their testimonies were either templated or manufactured. At the stage of bail, the defence cannot cross-examine their testimonies.

- Mere presence in a WhatsApp group (not banned organizations) or attending meetings without any overt act or instigation, cannot be construed as participation in a criminal conspiracy.

- Athar Khan and Shadab Ahmed have not posted a single message in the DPSG group demonstrating intention of blocking roads or causing riots.

- The only overt act attributed to Saleem Khan is the turning away of a CCTV camera, for which he has already been granted bail in the FIR No. 60/2020.

- There is no evidence of receipt of money by Khalid Saifi for the procurement of firearms. He is a resident of Chand Bagh and it cannot be suspicious that he was located in the area

Shifa-ur-Rehman and Meeran Haider

The prosecution claimed that Shifa-ur-Rehman and Meeran Haider managed protest sites across Delhi, attended meetings of the Jamia Coordination Committee (JCC) at the Alumni Association of Jamia Millia Islamia (AAJMI) office, and raised funds for the protests. The specific accusations against the two are:

- Shifa-ur-Rehman: As President of AAJMI, he generated fake bills to cover up money used in the conspiracy. The Court holds that “the possibility of misuse of the position … cannot be ruled out”

- Meeran Haider: Alleged to have delivered inflammatory speeches at the behest of Umar Khalid and raised funds for the riots

At the time of the hearings, Shifa had been in custody for 1956 days and Meeran for 1981 days. The judgment does not explain how passive presence in various meetings or association with lawful student and alumni organisations indicate intention, preparation, or participation in a terrorist act or conspiracy.

- The allegations of fund-collection or fraud are uncorroborated by forensic or direct evidence, and sustained solely based on vague and uncorroborated testimony of protected witnesses. Since the veracity of the prosecution witnesses can only be tested at trial, it is illogical to accept their statements as gospel truth at this stage.

- There are no allegations of AAJMI itself having engaged in any unlawful activities. Applying Watali’s standard of ‘broad probabilities,’ which “possibility” cannot be “ruled out”: Shifa “misusing” his Presidency of AAJMI, or belated statements from anonymous witnesses being unreliable?

- No speech or message has been attributed to the accused wherein they can be seen inciting or participating in violence. Several documents on record, including correspondence and public statements, show them consistently discouraging unlawful and disruptive activity.

Gulfisha Fatima

Gulfisha was accused of “playing a pivotal role in mobilising women for the protests” through the WhatsApp groups ‘Auraton ka Inqalab’ and ‘Warriors.’ She is also alleged to have blocked the road near Jafrabad Metro Station and instigated women to violence. She is further accused of receiving funds from co-accused Tahir Hussain to support the riots.

At the time of hearings, Gulfisha had been in custody for 1973 days.

- The chats of the ‘Auraton ka Inqalab’ group are not a part of the case record, and the chat of the ‘Warriors’ group pertain only to participation in legitimate peaceful protests

- There are no reports of chakka-jaam at Jafrabad metro station on February 22, 2020. The protest was peaceful and completely non-violent.

- The allegation that Hussain “handed over a bundle of notes” to Gulfisha for some illegal purpose stands solely on the testimony of Protected witness Saturn. The prosecution has not explained the amount allegedly given or the date on which such money was handed over.

On the Argument of Parity

All the nine accused drew the Court’s attention to the factual parity between their cases and the cases of Devangana Kalita, Natasha Narwal, and Asif Iqbal Tanha. All nine were dismissed, with the Court sheltering behind the Supreme Court’s caveat that the earlier Delhi High Court bail orders “shall not be treated as precedent.”

The injustice is the starkest in Gulfisha Fatima’s case, which is materially indistinguishable from Devangana and Natasha’s. The High Court takes great pains to draw a distinction, seizing on the absurd claim that Gulfisha’s creation of WhatsApp groups to mobilise women for protests set her apart.

The order in Sharjeel Imam & Ors v State of Delhi can be read here:

Tasleem Ahmed and the Justification for Prolonged Incarceration

In a separate order, the Delhi High Court denied bail to Tasleem Ahmed holding that since the maximum punishment prescribed under Sections 18 and 20 of the UAPA is life imprisonment, therefore prolonged incarceration “cannot be the sole factor for grant of bail.” This is a wilful perversion of Najeeb and a betrayal to the Constitutional promise of Liberty. At the time of the hearings, Tasleem Ahmed had been incarcerated for 1901 days.

The Court further held that “majority of delay is attributable to the accused.” In five years, Ahmed has not taken even a single day’s adjournment.

This argument was popularised earlier this year by former Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, and instantly picked up by the alt-right media who dismiss the prolonged pre-trial incarceration of the Delhi riots accused by claiming they are ‘forum shopping.’ CJP has debunked this myth, reporting how the glacial pace of the case has been systemically manufactured through institutional churn and prosecutorial obstruction. The bail pleas were filed in 2022, and were passed on to three different Benches. Twice, they had to be heard afresh since judges who reserved the verdict did not pronounce the order and were subsequently transferred. The pleas have been listed, on average, 60–70 times each. Listings were cancelled majorly because special benches failed to assemble (44 occasions for Imam alone) or judges were unavailable due to workload or roster conflicts[6].

The order in Tasleem Ahmed v State of Delhi can be read here:

The Delhi High Court’s reasoning in both these orders is not Constitutionally-oriented, but outcome-oriented. The same Court which, in 2021, examined the merits of the case against the co-accused and found it bereft of any specific or particularised evidence not coated in “alarming and hyperbolic verbiage,” now claims to avoid the merits while uncritically leaning on the prosecution’s narrative to sustain detention.

What is to be Done?

After five years, the Delhi High Court was able to look the people of India in the eye and declare that the trial is “progressing at a natural pace,” rationalising that “a hurried trial would also be detrimental to the rights of both the Appellants and the State.”

The Delhi Riots Conspiracy case is one of ritualised silencing: incarceration without a speedy trial, prosecutions on conspiratorial hysteria, and courts filling in narrative gaps with inferences, assumptions, and outright absurdities. Sharjeel Imam and his co-accused are prisoners of the Hindutva State – hostages to the game of nation-building, and a warning to Indian Muslims and all marginalised people to hold their tongue.

But “for a human being not to speak is to die.” [7]

The UAPA is presented as the public’s weapon to defend society from terrorism. In reality, it is a distractionary alarm-bell to silence those who speak truth to power. The law does not stand above the social class-structure as a neutral protector, but preserves and serves the interests of the dominant and powerful class, embodied by the State and its machinery. By branding dissent as “terrorism,” the state shields the terror it unleashes everyday – through poverty, communal violence, dispossession, and repression.

The venomous web of the UAPA collapses the facade of ‘separation of powers,’ until the same script echoes from sub-inspector Arvind Kumar, to legal officers representing the state in constitutional courts and then, finally even significant sections of the judiciary. History will record that while the Indian judiciary and its judges searched hard to uncover communal provocation in Umar Khalid’s speech, they appeared blind to the seething hate and open calls to violence by those in positions of power, like the ‘honourable ministers’ Kapil Mishra, Anurag Thakur, and Parvesh Verma.

There have been persistent calls that a law such as the UAPA must be repealed. There have been strong appeals that political prisoners must be released. Above all, Courts must serve people’s justice. It is easy to succumb to hopelessness in the face of the mammoth State apparatus. At such a time, hope flickers through the words of Umar Khalid.

In a speech recorded before his arrest, Umar told us that “They are silencing us and putting us behind bars of jails, but they are also putting you behind bars of fear and falsehood.” Fear is an authoritarian state’s greatest weapon.

Remember this is what the State fears. Voices, like the ones at Shaheen Bagh. Alliances, like the ones at Elgar Parishad. Leaders, like Meeran Haider and Gulfisha Fatima.

Remember Umar’s final appeal. “Don’t be afraid. Speak up against injustice. Ask for the release of those who are being implicated in false cases. Raise your voice against every kind of tyranny.”

How will we speak?

(The legal research team of CJP consists of lawyers and interns; this legal resource has been worked on by Raaz)

Footnotes

- Abdul Rahman, ‘Five years since Delhi was set on fire by the right and the victims were blamed,’ (People’s Dispatch, 22 February 2025)

- Betwa Sharma, ‘How Kapil Mishra Allegedly Broke The Law, Was Never Prosecuted & Became Delhi’s Law Minister’ (Article 14, 20 March 2025)

- CJP Team, ‘Delhi Riots 2020: Stalled justice & the architecture of indefinite detention, FIR 59/2020 in perspective’ (Citizens for Justice and Peace, July 2025)

- Gautam Bhatia, ‘A Graveyard for Civil Rights Jurisprudence: The Devangana Kalita Bail Order’ (ICLP Blog, May 2023)

- Ibid.

- Supra, 3

- Varavara Rao, ‘The Word is the World’ (Captive Imagination)

[1] Abdul Rahman, ‘Five years since Delhi was set on fire by the right and the victims were blamed,’ (People’s Dispatch, 22 February 2025)

[2] Betwa Sharma, ‘How Kapil Mishra Allegedly Broke The Law, Was Never Prosecuted & Became Delhi’s Law Minister’ (Article 14, 20 March 2025)

[3] CJP Team, ‘Delhi Riots 2020: Stalled justice & the architecture of indefinite detention, FIR 59/2020 in perspective’ (Citizens for Justice and Peace, July 2025)

[4] Gautam Bhatia, ‘A Graveyard for Civil Rights Jurisprudence: The Devangana Kalita Bail Order’ (ICLP Blog, May 2023)

[5] Ibid

[6] Supra, 3

[7] Varavara Rao, ‘The Word is the World’ (Captive Imagination)

Related:

UAPA: Delhi HC denies bail, Umar Khalid’s Incarceration to Continue

Delhi court rejects application to handcuff Umar Khalid & Khalid Saifi

Umar Khalid’s speech prima facie not acceptable, obnoxious: Delhi HC

Protest was secular, chargesheet is communal: Dr. Umar Khalid’s counsel

Umar Khalid bail hearing: Counsel points out “cooked up” witnesses

Chargesheet against me looks like a film script: Umar Khalid to court