Rajasthan’s Public Shaming: Police humiliation practices defy law and human dignity Rajasthan Police’s 2025 public parading of suspects—through forced haircuts and gendered humiliation—defied court orders and due process amid official silence

28, Jan 2026 | CJP Team

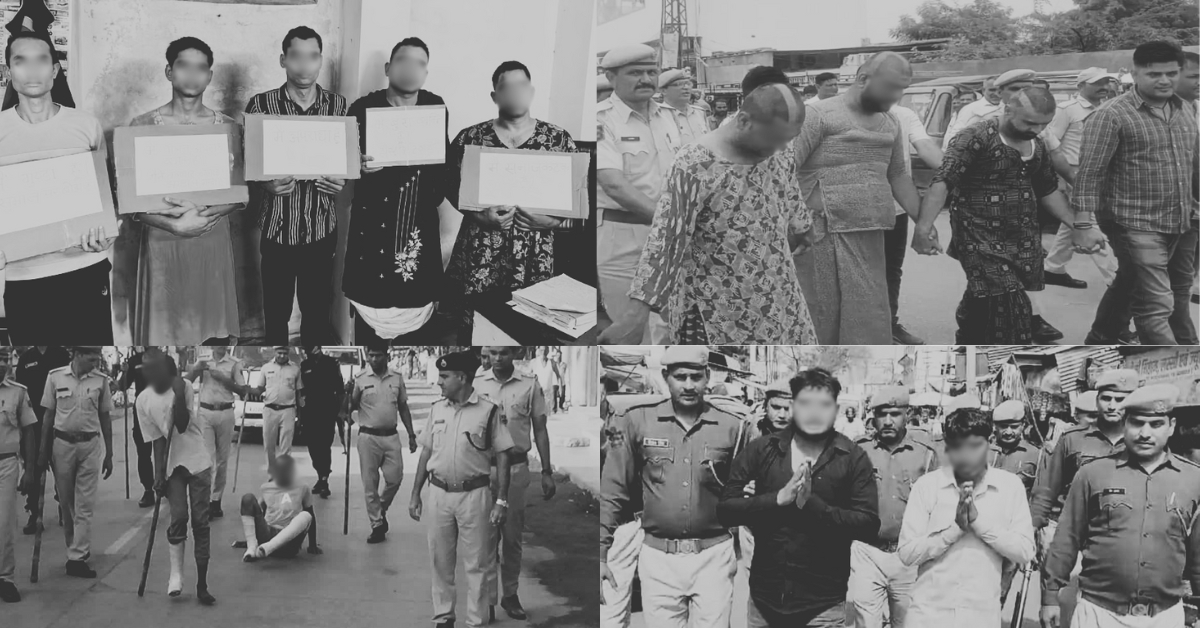

A stark contradiction now exists between the constitutional mandate on the statute books and our jurisprudence and the extra-constitutional ‘rituals’ practiced by police on the streets of Rajasthan. A layered analysis through 2025, based on media reports reveals recurring and disturbing patterns.

We have been observing the systemic normalisation of public shaming—a practice where police, not the judiciary, effectively deliver a public verdict. This is not due process; it is a coercive performance of degradation, rendering the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ a fiction in practice. The evidence compiled herein is clear, suspects, who should still be shielded by the presumption of innocence, are paraded before cameras and crowds. They are forced into women’s clothes in a calculated act of gendered humiliation. Their heads are forcibly shaved. They are marched down roads with visible and severe injuries; limping on fractured legs or, in some cases, even made to crawl on the road!

This conduct is not the sporadic egregious misconduct of a few officers. It is a defiant, systemic practice that stands in direct contravention of established law. It squarely violates the unambiguous prohibitions set by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Prem Shankar Shukla v. Delhi Administration (1980) SCC (3) 526. It is a profound violation of Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees every person—accused or not—the right to life and human dignity.

Significantly, this recurring illegality continues in open defiance of advisories from the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Rajasthan DGP’s own circulars forbidding these very acts. The state’s top police leadership, by failing to enforce its own directives, has transitioned from silent spectator to complicit enabler. This resource is a legal examination of this practice. It details how the instruments of law are being perverted to enact a form of public justice, replacing the sanctity of the courtroom with the irreversible, prejudicial judgment of the crowd.

A map of humiliation: the state-wide trend of extra-legal parades

The colonial practice to parade accused before public and media as some hunted animal trophy is worst form of abuse of human rights of an individual. The British adopted this practice to ensure that the people of India remain fearful and subservient to handful of foreign rulers (who’s police forces were trained to turn against their own). In large part, they were successful in ensuring brute control, but that such tendencies should spiral in free ‘democratic India?

Shockingly, these extra-legal “arrest rituals” are not isolated incidents but part of a systemic practice across Rajasthan this past year that our team has documented. We present a detailed legal analysis.

- Gendered humiliation as punishment

Few practices reveal the collapse of constitutional restraint more starkly than the police’s resort to gendered humiliation as a tool of punishment. Across Rajasthan, police officers have repeatedly turned to misogynistic tropes—forcing accused men into women’s clothing, half-shaving their heads, and parading them before jeering crowds—as instruments of moral retribution rather than lawful procedure. These acts, staged in full public view were documented through 2025. Often, they were visually documented for social media dissemination. These unlawful acts are not by any means, spontaneous lapses of discipline. They represent a conscious performance of power—where masculinity, shame, and violence are choreographed into public spectacle.

Even when the police claim that the accused were found disguised in women’s clothes at the time of arrest, such an explanation cannot justify their public parading in the same attire. The act of displaying them before crowds in those clothes—long after custody has been secured—serves no investigative purpose. It is an act of deliberate humiliation, stripped of any legal rationale, and therefore per se illegal. It transforms supposed evidence of arrest into a spectacle of degradation, meant to mock rather than prosecute.

The incidents that follow demonstrate how the police have systematically weaponised gender stereotypes to degrade the accused. In Sikar, Udaipur, Nagaur, Jhunjhunu, and Dausa, law enforcement transformed arrests into orchestrated parades of humiliation, targeting not only the individual’s liberty but their dignity itself. Each case exposes how gendered humiliation has evolved into an informal yet recurring mode of punishment—public, performative, and patently unlawful.

- Sikar: After arresting two men for allegedly killing a bull by running it over with an SUV on October 1, 2025, Nechwa police subjected them to such degradation. Claiming the men were found hiding in women’s clothes, officers half-shaved their heads and then paraded them through the public market, forcing them to wear women’s nightgowns. This spectacle was designed to incite public anger, with crowds reportedly shouting for the men to be hanged. (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

Departmental endorsement of Sikar Police’s illegal parade

This defiance of law is not merely a station-level anomaly, it is amplified by a glaring departmental contradiction, perfectly captured by the Sikar parade incident.

This illegal parade, designed to incite public anger, was then officially endorsed by the force’s public relations arm. Despite internal directives from the DGP (such as the detailed SOP dated September 21, 2023) explicitly forbidding such acts of humiliation, the official @PoliceRajasthan social media handle broadcast a video of this very parade. It was framed as a righteous act, captioned, “Rajasthan Police: A befitting reply to human cruelty”, thereby publicly celebrating a blatant violation of law as a policy success.

- Udaipur: Five men arrested by Hathipole police for rioting and assault with a sword were paraded on November 1 in a manner clearly intended to humiliate. Justifying the act with the claim that the accused were planning to flee in female attire, police forced all five to dress in women’s clothes. To amplify the shame, they were made to wear placards around their necks with slogans like “I am a burden on society” and “I am a criminal” as they were marched through the city. (Report in The Mooknayak).

Image Credit: The Mooknayak

- Nagaur: On August 1, in Merta town, three men accused of a lottery scam—a crime they allegedly committed while disguised in female attire—were subjected to a multi-layered shaming ritual. Police shaved their heads and then marched them from the bus stand to the court while forcing them to wear the women’s salwar suits. (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

Throughout the parade, officers forced the men to keep their hands folded and repeatedly chant, “We made a mistake.”

- Jhunjhunu & Dausa: This tactic of weaponising an accused’s disguise was repeated across districts. In Surajgarh (Jhunjhunu), on July 20, the SHO paraded a man accused of attacking a sarpanch in the salwar suit he was allegedly wearing while in hiding. (Reports in Dainik Bhaskar and Patrika).

Image Credit: Rajasthan Patrika

Similarly, in Dausa, police arrested two men for attacking officers. After finding them hiding in women’s clothes, police paraded them through the village in that same attire, forcing them to walk with folded hands and issue a public warning that “No one should do this, or they will face the same consequences.” (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

2. Parading the injured accused/suspects: spectacles of cruelty

In several cases, police have paraded accused. Several of these accused were visibly and severely injured, turning a “spot verification” or “Medical Examination” procedure into a public display of suffering.

- Kota: On May 22, in a shocking parade from Kanwas, police paraded two murder accused who were severely injured, allegedly from fleeing arrest. Both men had their legs in plaster casts. Media reports explicitly described one accused, Atiq, whose both legs were broken, crawling or ‘dragging himself’ on the road. The second accused, Deepak, limped painfully alongside on a crutch. The Kota Rural SP justified this as “spot verification.” He said that “action was taken to have the accused verify the scene and to prepare a site map of the incident. Since both had sustained injuries, they were taken to the spot on foot” as ETV Bharat Rajasthan reported. (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: ETV Bharat Kota

- Jaipur: On January 23, Vidhyadharnagar police paraded five men accused in a high-profile robbery and murder case. Two of the men had sustained fractured legs from falling in a ditch and were in plaster casts. (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

Police forced these injured men to walk, limping and supported by officers, from the police vehicle to the crime scene and even to the victim’s house.

- Tonk: On September 30, The Times of India reported that the Tonk Police arrested three men for allegedly molesting a 13-year-old girl and threatening her with an acid attack. During the public “spot verification,” one of the accused, unable to walk, was filmed dragging himself on the road, while the other two limped beside him as locals cheered. During the parade, a large crowd gathered and chanted slogans of “Tonk Police Zindabad.” (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

- Kotputli: On July 1, four men accused of murdering a liquor contractor were arrested after a police “encounter” in which all four were shot in the legs. Immediately following their medical treatment, police paraded the injured accused, limping from their fresh gunshot wounds, in a “procession” through the town.

- Karoli: On February 25, two men accused of firing over a payment dispute at a salon were arrested after being injured, allegedly by falling on stones while fleeing. Police then paraded the two men, who were visibly limping, and forced them to walk through the city with folded hands, apologising to the public. (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

3. Rituals of degradation: shaving, placards, and drums

Beyond gendered humiliation, police employ other theatrical methods of degradation designed to shatter an accused’s self-respect.

- Baran: On June 3, demonstrating that even an alleged intent to commit a crime warrants public degradation, police arrested 12 men for planning a robbery at a petrol pump. Before any trial, police shaved the heads of the accused and paraded them through the city market, forcing them to join their hands and publicly apologise. (Report in NDTV Rajasthan).

Image Credit: NDTV Rajasthan

- Pali: On October 28, the Pali Police orchestrated a highly theatrical shaming procession for three murder accused. Officers hired dhols (drums) to beat as they marched the men from Ambedkar Circle to the court. The accused, who were visibly limping, were forced to wear clothes with the label ‘Hardcore History-sheeter’ printed on them and beg for forgiveness.

During the parade, a woman tried to reach the accused to slap them, but the police stopped her

- Hanumangarh: On October 30, the Gogamedi police arrested six men, alleged to be members of a criminal gang. As a form of summary punishment, police forcibly cut their hair and then paraded them through village. (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

The men were seen limping and attempting to hide their faces in shame during the procession.

Footage Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

- Udaipur: On October 5, combining multiple forms of humiliation, Bhupalpura police paraded two men accused of a stabbing. The men were forced to walk while visibly limping from injuries sustained during their arrest, and police had half-shaved their heads to maximise their public disgrace.

The accused men were marched in this state for approximately two kilometers to “recreate the scene.”

4. General parades: “sport verification” as public spectacle

Even in cases without overt torture, the routine practice of parading suspects for “spot verification” is used as a pretext for public shaming.

- Jodhpur: On August 20, after arresting suspects in a firing case, Jodhpur police paraded the accused on foot from the police station to the nearby crime scene in the middle of the market, justifying it as the “last day of remand” and a “spot inspection.” (Report in Amar Ujala.

Image Credit: Amar Ujala

- Bikaner: On July 28, Lunkaransar police paraded six men, accused of attacking a shopkeeper, through the same market where the incident occurred, forcing them to walk to the hospital. The parade drew a large crowd, which turned the procession into a “julus” (spectacle). (Report in Dainik Bhaskar).

Image Credit: Dainik Bhaskar

- Jaipur: In a separate Vidhyadharnagar case, on June 3, two men arrested for allegedly trying to free a suspect from police custody and tearing a constable’s uniform were paraded at the scene of the incident, where they were forced to fold their hands and apologise. (Report in Patrika).

Image Credit: Patrika

- Churu: On September 21, Taranagar Police paraded a young man accused of allegedly stabbing a female student. He was marched from the police station through the main market and bus stand to “send a message.” According to Dainik Bhaskar, the SHO was quoted as saying, “This is the fate of those who commit crimes.”

Link: https://dai.ly/x9qx8kw

The statutory framework: due process vs. public spectacle

The statutory framework governing arrest, detention, and investigation in India is exhaustive and focuses entirely on procedural correctness, investigative necessity, and the rights of the accused. This framework is designed to protect the individual from the arbitrary exercise of state power.

Conspicuously absent from the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS), and its predecessor, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, is any provision, power, or procedure that legitimises the public parading, shaming, or forced humiliation of an accused or suspect. The police actions documented in Rajasthan are not a mere over-extension of authority but they are in direct contravention of black-letter law.

The limited and defined powers of arrest

The police’s power to arrest is not absolute. It is narrowly defined, primarily under Section 35 of the BNSS, 2023 (which corresponds to Section 41 of the CrPC, 1973). This section outlines the specific circumstances under which a police officer may arrest without a warrant. The entire purpose of this power is to prevent the commission of further offenses, ensure a proper investigation, or secure the accused’s presence at trial. It does not grant any power to inflict summary punishment or public humiliation.

The manner of arrest is detailed in Section 43 of the BNSS, 2023:

(1) In making an arrest the police officer or other person making the same shall actually touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested, unless there be a submission to the custody by word or action:

Provided that where a woman is to be arrested, unless the circumstances indicate to the contrary, her submission to custody on an oral intimation of arrest shall be presumed and, unless the circumstances otherwise require or unless the police officer is a female, the police officer shall not touch the person of the woman for making her arrest.

(2) If such person forcibly resists the endeavour to arrest him, or attempts to evade the arrest, such police officer or other person may use all means necessary to effect the arrest.

(3) The police officer may, keeping in view the nature and gravity of the offence, use handcuff while making the arrest of a person or while producing such person before the court who is— (i) a habitual or repeat offender; or (ii) a person who escaped from custody; or (iii) a person who has committed offence of organised crime, terrorist act, drug related crime, illegal possession of arms and ammunition, murder, rape, acid attack, counterfeiting of coins and currency-notes, human trafficking, sexual offence against children, or offence against the State.

While Sub-section (3) introduces specific grounds for handcuffing, its legal basis remains tied to preventing escape and ensuring safety—not for public display. The parading of an accused in handcuffs, often when they are already subdued or injured, serves no legitimate custodial purpose.

The absolute prohibition on unnecessary restraint

The most blatant statutory violation in these public parades is the breach of Section 46 of the BNSS, 2023 (mirroring Section 49 of the CrPC). This provision is not ambiguous and leaves no room for discretion. It mandates:

“The person arrested shall not be subjected to more restraint than is necessary to prevent his escape.”

Forcing an accused to wear women’s clothing, shaving their head, hanging a placard around their neck, or forcing them to limp through a market while injured is, by any definition, “more restraint than is necessary to prevent his escape.” These acts are illegal, punitive, and fall entirely outside the police’s lawful authority.

Provisions pertaining to the use of handcuffing

The legal framework governing handcuffs in India was historically undefined, with no explicit provision in the previous CrPC, 1973. Their use was permissively shaped only by Supreme Court directives, notably in Prem Shanker Shukla v. Delhi Administration (1980) SCC (3) 526 and Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) guidelines (2010), which strictly limited it to a measure of last resort for securing restraint—not as a routine tool.

The new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), in Section 43(3), for the first time codifies this power, but only for exceptionally narrow and grave circumstances, such as for a habitual or repeat offender, a person who escaped custody, or one who has committed specified serious offences like organised crime, terrorism, murder, or rape.

While police may justifiably argue that handcuffs are necessary to secure an accused during spot verifications, medical examinations, or production before the court, the incidents documented across Rajasthan tell a different story. The visual evidence shows handcuffs being weaponised not for legitimate restraint, but as a prop for public shaming—an integral part of the illegal parade. This unnecessary, performative demonstration of power is a per se unconstitutional and illegal act, designed to inflict humiliation rather than uphold the law.

Zoological strategies repugnant to Article 21: SC’s definitive mandate in Prem Shankar Shukla

The foundational and most authoritatively-violated law on this matter remains the Supreme Court’s 1980 judgment in Prem Shankar Shukla v. Delhi Administration (1980) SCC (3) 526. This ruling did not just restrict handcuffing; it condemned the entire mindset behind public degradation as an affront to the Constitution. The Court declared that handcuffing is “prima facie inhuman” and “arbitrary,” calling it a “zoological strategy” that is “repugnant to Article 21.”

Addressing the exact ritual of parading, the Court observed:

“But to bind a man hand-and-foot, fetter his limbs with hoops of steel, shuffle him along in the streets and stand him for hours in the courts is to torture him, defile his dignity, vulgarise society and foul the soul of our constitutional culture.” (Para 22)

The Court established that the “convenience of the custodian” (Para 24) is irrelevant. Handcuffing is not a routine procedure but an “extreme measure” (Para 25) that can only be justified as the “last refuge, not the routine regimen” (Para 25). The bench explicitly rejected the idea that the “nature of the accusation” (Para 31) is a valid criterion. Instead, the only determinant is a “clear and present danger of escape” (Para 31), which must be based on “clear material, not glib assumption” (Para 31).

Crucially, the judgment set a non-negotiable procedural safeguard: police cannot act unilaterally. Even in those rare, extreme cases, the officer must:

“…record contemporaneously the reasons for doing so… The escorting officer, whenever he handcuffs a prisoner produced in court, must show the reasons so recorded to the Presiding Judge and get his approval. Otherwise… the procedure will be unfair and bad in law.” (Para 30)

The Court concluded by condemning the practice as a “barbarous bigotry” and “an imperial heritage, well preserved” (Para 33), making it clear that such “animalising” (Para 23) displays are summary punishments “vicariously imposed at police level” (Para 31) and have no place under the Constitution.

The judgement of Prem Shankar Shukla v. Delhi Administration (1980) can be read here

Police duty is arrest, not punishment: the Omprakash judgment

In Omprakash and Ors. v. State of Jharkhand (2012) 12 SCC 72, the Supreme Court stressed the fundamental limits of police duty. The Court observed that the police designated role is not to deliver summary punishment, stating “It is not the duty of the police officers to kill the accused merely because he is a dreaded criminal. Undoubtedly, the police have to arrest the accused and put them up for trial.” (Para 42).

This observation highlights the principle that the police’s sole, lawful function is to bring an accused before the judiciary, not to usurp the judicial role by inflicting punishment—be it through extra-judicial killings or, by extension, through acts of public degradation.

The judgement of Omprakash and Ors. v. State of Jharkhand (2012) 12 SCC 72 can be read here

A Parallel Trial: Supreme Court on the illegality of media parades of accused

The Hindu reported that on August 28, 2014, the Supreme Court directly condemned the practice of police parading suspects before the media, viewing it as a serious threat to the constitutional guarantee of a fair trial. During the 2014 hearings for the Public Union for Civil Liberties & another v. The State of Maharashtra & Ors. (CDJ 2014 SC 831), a three-judge bench led by then-Chief Justice R.M. Lodha expressed strong disapproval of this practice. The Chief Justice was unequivocal, stating:

“Media briefings by investigating officer during on-going investigations should not happen. It is a very serious matter. This issue touches upon Article 21 [right to life and liberty including fair trial].”

The bench, which also included Justice Kurian Joseph, noted that this conduct prejudices the accused before they are even charged. Justice Joseph observed that by releasing unproven statements, “a parallel trial is run in the media,” which affects the fundamental rights of the accused and creates an indelible stigma.

Home Ministry’s advisory on media policy and ban on public parading of accused persons

The systemic defiance of legal norms is further evidenced by the police’s flagrant disregard for binding directives from the Union Government itself. As far back as April 1, 2010, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) issued a comprehensive “Advisory on Media Policy of Police” (F. NO.15011/48/2009-SC/ST-W) to all states. This advisory explicitly mandates precautions to protect the dignity of those in custody. Guideline VI(a) of the memorandum is unequivocal that “arrested persons should not be paraded before the media.”

Para (VI) reads as follow;

“Due care should be taken to ensure that there is no violation of the legal, privacy and human rights of the accused/victims.

- Arrested persons should not be paraded before the media.

- Faces of arrested persons whose Test Identification Parade is required to be conducted should not be exposed to the media.”

It further instructs that “due care should be taken to ensure that there is no violation of the legal, privacy and human rights of the accused/victims.” The MHA advisory, which forms the basis for subsequent state-level circulars, also directs that any deviation “should be viewed seriously and action should be taken against such police officer/official.”

The recurring spectacles in Rajasthan are therefore a direct violation of these long-standing, explicit instructions from the very ministry overseeing internal security.

The MHA advisory dated April 1, 2010 can be read here

Section 29 of the Rajasthan Police Act, 2007

The very statute governing the state’s police, the Rajasthan Police Act, 2007, establishes a clear, affirmative obligation for officers to follow the law. Section 29 of the Act details the duties and responsibilities of every police officer. Crucially, Section 29(i) mandates that an officer shall “perform such duties and discharge such responsibilities as may be enjoined upon him by law or by an authority empowered to issue such directions under any law.” This provision makes adherence to all legal mandates—including constitutional protections, Supreme Court judgments, and internal departmental circulars—a fundamental and non-negotiable component of an officer’s statutory duty.

Circulars/advisory issued by the DGP, Rajasthan

This reported illegality is not just a violation of MHA advisories but also a direct contravention of the Rajasthan Police’s own internal guidelines. On October 18, 2013, the Director General of Police (DGP), Rajasthan, issued a specific advisory to all District Police Superintendents and G.R.P. Ajmer/Jodhpur regarding police-media relations. This directive explicitly aimed to prevent the very practices now seen across the state. Para (vi) of the advisory clearly mandates:

“It should always be kept in mind that; (a) the arrested person should not be paraded before the media. (b) The face of the accused whose identity is to be paraded should not be shown to the media.”

The DGP, Rajasthan’s instructions dated October 18, 2013 can be read here

Rajasthan Police’s SOP strictly prohibits using handcuffs for “public ridicule, harassment, or humiliation”

On September 21, 2023, the Additional Director General of Police (Crime), Rajasthan, issued a detailed Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) acknowledging that handcuffing and displaying accused was being done “routinely,” a practice that “humiliates a person,” “hurts their self-respect,” and “tarnishes the image of the police.”

Citing the Rajasthan High Court’s 2023 order (supra) and the Supreme Court’s mandate in Prem Shankar Shukla (supra), the SOP strictly prohibits using handcuffs for “public ridicule, harassment, or humiliation” or merely for the “convenience of the escort team.”

The SOP mandates that handcuffs are a last resort, to be used only in “exceptional circumstances” (e.g., the prisoner is violent, dangerous, or a high escape risk) and requires prior court approval. The reasons for their use must be meticulously recorded in the police station’s daily diary (Roznamcha Aam) before application.

The SOP also explicitly forbids the routine handcuffing of “Satyagrahis, persons holding dignified positions in public life, journalists, [and] political prisoners,” and states that even if justifiably handcuffed, they must not be paraded. It directs senior officers (IGPs and SPs) to ensure “verbatim” compliance with these instructions.

The ADGP, Rajasthan’s directive dated September 21, 2023 can be read here

“Will not conduct a public parade”: DGP’s January 2025 SOP directly bans shaming rituals

The legal prohibitions against these practices were reinforced with the issuance of a new “Standard Operating Procedure for the use of handcuffs” by the Director General of Police, Rajasthan, on January 15, 2025. This SOP was issued to align with Section 43(3) of the new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023, which codifies the power to use handcuffs for specific, grave offenses (e.g., habitual offenders, terrorism, murder, rape, organised crime).

However, the directive unequivocally states that even for these accused, handcuffs are only permissible in “exceptional circumstances” where there is a “clear and present danger” of escape or violence, and the reasons must be “clearly recorded.” Most significantly, the 2025 SOP directly confronts and bans the very rituals this resource documents. It explicitly commands:

“The police officer, after handcuffing, will not conduct a public parade of the prisoner.”

Furthermore, it directly targets the police practice of broadcasting these events, instructing officers to: “…take special care that after handcuffing, photos or videos of the prisoner are not uploaded to social media.”

This latest directive from the state’s top police office leaves no ambiguity, explicitly forbidding the exact conduct of parading suspects and disseminating the footage.

The directions of DGP, Rajasthan dated January 15, 2025 can be read here

Rajasthan High Court’s condemnation on illegal handcuffing

On May 26, 2023, the Rajasthan High Court’s order (Jodhpur Bench) in D.B. Habeas Corpus Petition No. 156/2023, the Court, while disposing of the petition, issued several key directives. The operative part of the order mandates the respondents to conduct an expeditious inquiry into the incident and against the delinquent officers, including those already suspended. The Court directed that the Inspector General of Police (IGP) must personally monitor the progress of this inquiry.

Furthermore, the Court explicitly ordered the IGP to ensure that the directions issued by the Supreme Court [notably in Prem Shanker Shukala v. Delhi Administration (1980) SCC (3) 526, which prohibit routine handcuffing, are followed “in letter and spirit” throughout his jurisdiction.

The High Court’s take on the handcuffing was one of strong condemnation. It found the action of handcuffing the petitioner’s son—who was not formally arrested and was hospitalised with a fractured leg, rendering him unable to walk—to be “inhuman” and “absolutely illegal and unconstitutional.” The Court noted that the very presence of handcuffs at the general ward bed of an unarrested accused, who alleged he was fettered at night, “firmly established” the illegality and was a clear violation of constitutional mandates, dismissing the suspension of officers as an “eye-wash.”

The order dated May 26, 2023 of the Rajasthan High Court can be read here

The judicial condemnation of public parades extends beyond a single state

Apart from the Rajasthan High Court, this concern is also shocking courts across the country as well, as the Gujarat High Court, in R/WPPIL/153/2018, Bhautik Vijaybhai Bhatt v. Director General of Police, addressed this issue directly. The Public Interest Litigation sought a writ of mandamus to stop police from “taking out procession of accused persons by handcuffing them… and beat such accused persons in public place.” In response, the Additional Director General of Police filed an affidavit assuring the Court of “proposed draft instructions” to be issued to all officers.

The High Court’s order dated May 7, 2019, specifically recorded that these new instructions would ensure that accused persons are “not parading them in public at large” or given any “maltreatment.” The affidavit, accepted by the Court, affirmed that accused must be “protected from mob violence” and taken to the police station or Magistrate “in a dignified manner by protecting their individual status.” The Court disposed of the PIL by directing the state to issue this circular, reinforcing that legal guidelines must be “strictly complied with.”

The order of Gujrat High Court dated May 7, 2019 can be read here

No parading of accused/suspects: Hyderabad High Court (Telangana HC)

The New Indian Express reported that on June 21, 2018, a division bench of the Hyderabad High Court comprising Chief Justice Kalyan Jyoti Sengupta and Justice PV Sanjay Kumar recently expressed their “extreme displeasure” over parading of accused in front of media and television channels. The observation has evoked a positive response and won accolades from different walks of life. The judges asserted that the bench would pass orders prohibiting the practice.

Subsequently, the High Court refused a request to grant the DGP, Andhra Pradesh, two weeks to file an affidavit in the case. The bench, demonstrating its urgency on the matter, strongly remarked that “You are treating the accused-suspects as animals that is why you are allowing them before the media without any respect to their Right to Privacy which is a fundamental right. We will grant only a week’s time to you to file the affidavit as per our earlier direction” as the Deccan Chronicle reported

Rights of the accused: protection and fair trail, not degradation

The law, far from sanctioning humiliation, builds a wall of protection around the accused. Section 38 of the BNSS, 2023 (mirroring Section 50 of the CrPC), mandates that when any person is arrested and interrogated by the police, he shall be entitled to meet an advocate of his choice during interrogation, though not throughout interrogation.

Furthermore, Section 51 of the BNSS, 2023 (regarding the medical examination of the accused), shows the law’s intent:

…it shall be lawful for a registered medical practitioner, acting at the request of any police officer… to make such an examination of the person arrested as is reasonably necessary in order to ascertain the facts which may afford such evidence…

The purpose of a medical examination is evidentiary—to find trace evidence on the accused or document injuries relevant to the crime. This provision is perverted when police parade suspects with injuries (like fractured legs), turning a procedure meant for legal and medical documentation into a spectacle of cruelty.

The core jurisprudential breach

These police conduct tears at the very fabric of Indian criminal jurisprudence.

- Violation of Article 21 (Dignity): The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the right to life under Article 21 includes the right to live with human dignity. Public shaming, forced haircuts, and gendered humiliation are a profound assault on that dignity.

Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which guarantees the “right to live with human dignity.” This is the “most precious right” afforded to “every person,” a guarantee that is not suspended upon accusation or arrest. As the Supreme Court has affirmed in PUCL v. State of Maharashtra [Criminal Appeal No. 1255 of 1999] that, “even the State has no authority to violate that right.” (Para 7)

The judgement of PUCL v. State of Maharashtra [Criminal Appeal No. 1255 of 1999] can be read here

The only exception under Article 21 is that liberty can be curtailed, but only subject to the “procedure established by law”—which means through a fair trial, investigation, and conviction by a competent court. However, the police’s summary “punishments” in the name of spot verification and medical examination are per se illegal and a gross violation of the Constitution, as police have no authority to adjudicate guilt or inflict penalties.

This practice also fundamentally subverts Article 20(2) of the Constitution, which prohibits double jeopardy. When police inflict this public degradation, they are administering a “punishment” before any trial. Should the accused later be convicted by a court, they would have been subjected to two punishments—first, the illegal, irreversible public shaming by the police, and second, the judicial sentence. This police action is a brazen usurpation of judicial power, rendering the presumption of innocence a nullity.

In Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration, (1980) 3 SCC 488, the Supreme Court even condemned the inhuman and degrading treatment of prisoners, particularly the use of solitary confinement and held that fundamental rights do not end at the prison gates. It was emphasised that prison authorities must respect the dignity and rights of inmates under Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution. Thus, ‘human dignity’, which is apparently not a fundamental right was read as a part of Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

The judgement of Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration (1980) can be read here

In K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) 10 SCC 1 this Court affirmed right to privacy as a fundamental right under the Constitution, which was read as a right and a part of ‘life and liberty’ under Article 21. It was held that privacy encompasses autonomy, dignity, and the freedom to control their own personality.

The judgement of K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) can be read here

- Violation of Article 20(3) (Self-Incrimination): Forcing an accused to walk with folded hands and publicly chant “I made a mistake” is a form of compelled confession, obtained through duress and humiliation. It is a flagrant violation of the right against self-incrimination.

“I Made a Mistake”: forced confessions and the death of Article 20(3)

A core constitutional safeguard, enshrined in Article 20(3) of the Constitution, dictates that “No person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself.” This right against self-incrimination is so foundational that the law of evidence, both in Section 25 of the former Indian Evidence Act and its successor Section 23 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023, explicitly states that “No confession made to a police officer shall be proved as against a person accused of any offence.” These laws exist precisely because of the inherent risk of coercion in police custody.

The police rituals documented across Rajasthan—forcing accused men to chant “We made a mistake” or publicly apologise to crowds—are a flagrant and theatrical violation of these very safeguards. Such a “confession,” whether genuinely given in the privacy of a station or compelled by police pressure, is legally worthless and inadmissible as evidence.

Therefore, the only purpose of this public performance is extra-legal, to inflict humiliation, satisfy public anger, and enact a summary punishment. This practice is a performative and compelled act of self-incrimination. It does not matter if an accused has confessed; the police have no authority to broadcast this, let alone force its re-enactment as a public spectacle. By forcing an accused to apologise on camera, the police are not conducting an investigation; they are staging a verdict and illegally compelling a person to be a witness against himself, not before a court of law, but before a roadside mob.

- Destruction of the Presumption of Innocence: The accusation has to be proven in a court of law. When investigating authorities “play to the gallery,” they usurp the role of the judiciary. They declare the person guilty before a trial, inflicting an irreversible public sentence that no subsequent acquittal can ever undo. This damages the credibility and integrity of the entire justice system.

The D.K. Basu mandate: a judicial blueprint against custodial abuse

The most foundational legal standards for arrest and detention were established by the Supreme Court in its landmark judgment, D.K. Basu v. State of W.B. [(1997) 1 SCC 416]. The Court, deeply concerned with custodial violence and the abuse of police power, formulated a set of 11 mandatory requirements. These guidelines are not suggestions but “preventive measures” designed to ensure transparency, accountability, and the protection of an arrestee’s fundamental rights under Article 21. They create a non-negotiable procedural blueprint that stands in stark contrast to the arbitrary rituals of public shaming. The Court directed in Para 35 of the judgement that requirements to be followed in all cases of arrest or detention till legal provisions are made in that behalf as preventive measures.

These directives establish procedures to protect the rights of individuals during arrest and detention. Police officers must wear clear identification, and their details must be registered. An “Arrest Memo” must be prepared at the time of arrest, detailing the time and date, witnessed by a family member or local respectable person, and countersigned by the arrestee.

The arrestee must be informed of their right to have one friend or relative notified of their arrest and custody location. If this person lives out-of-district, police must notify them via the Legal Aid Organisation within 8-12 hours. The arrestee has the right to an injury inspection at arrest, recorded in a signed “Inspection Memo,” and must receive a medical examination by an approved doctor every 48 hours. They may also meet their lawyer during interrogation.

All arrest details must be recorded in a station diary, with copies of documents sent to the Magistrate. Furthermore, the district/state police control room must be informed of the arrest and custody location within 12 hours and display this information publicly.

The judgement of DK Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997) can be read here

No action from SHRC and DGP Rajasthan’s office

Despite an unambiguous legal framework, the compiled evidence reveals a systemic collapse of every accountability mechanism. The Rajasthan State Human Rights Commission (RSHRC), armed with suo moto powers to protect fundamental rights from illegal police practices, has remained a silent spectator. This inaction persists even as these “arrest rituals” have escalated since 2025, transforming from sporadic abuses into a monthly, viral spectacle of state-endorsed degradation.

This open defiance is amplified, not punished, with official police social media handles celebrating the violations. The institutional failure is absolute as the Rajasthan High Court has not taken suo motu cognizance, and the Director General of Police, despite his own clear directives (Jan 2025) forbidding these parades, has proven unable or unwilling to enforce them. The result is a state of perfect impunity, where the Constitution is openly defied, and the law, judiciary, and human rights commissions have, by their collective silence, become complicit enablers.

Related

What are the Rights against being handcuffed in India?