Liberty under Siege: Reclaiming the right to speedy trial from the grip of special laws Speedy trial is recognised as protection against indefinite detention, but if it comes only after years of confinement, it is no protection at all

18, Aug 2025 | CJP Team

On July 22, 2025, the Delhi High Court delivered its judgment in Naresh Kumar @ Pahelwan v. State of NCT of Delhi. The bail application was for proceedings emanating from FIR No. 55/2016, for which the accused had spent more than eight years in jail awaiting the conclusion of his trial. The appellant, an active gang member, was charged under various sections of the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act, 1999 (MCOCA). He had since been acquitted in all but one of the cases listed against him, including FIR No. 497/2011 – the foundational case for the MCOCA sanction.

MCOCA is among a class of ‘special laws’ enacted to combat grave threats to the social order. The Statement of Objects and Reasons of MCOCA notes that the existing legal framework was deemed “inadequate” to “curb or control the menace” of organized crime. To address this, the act introduces a set of bail conditions under Section 21 that depart significantly from the standard provisions of the Bhariyay Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) by shifting the burden of proof to the accused. Rider: The BNS 2023, under Section 479 also contains very stringent conditions for statutory bail. The said section limits the conditions for granting statutory bail to under trials.

[Section 436A of the CRPC provides for the procedure to be adopted in case the under trial is to be given statutory bail after spending a particular period under detention. In the older CrPC, if an under trial has spent half of the maximum period of imprisonment for an offence in detention, they must be released on a personal bond (not to be applied to offences which are punishable by death) BNSS, 2023 however, retains the said provision, and makes it further stringent. [1]

The stringent bail conditions under MCOCA and other special laws creates a tension between the presumption of innocence and the State’s power to restrict liberty. In Naresh Kumar, the High Court observes that the Supreme Court has consistently held that where trials under special laws are unduly delayed, the rigour of strict bail provisions must yield to the constitutional promise of liberty. The Court ruled that even the special provisions of MCOCA “cannot be construed in a manner that forecloses judicial scrutiny under Article 21.”

The complete judgment delivered in Naresh Kumar @ Pahelwan v. State of NCT of Delhi (2025) can be read here.

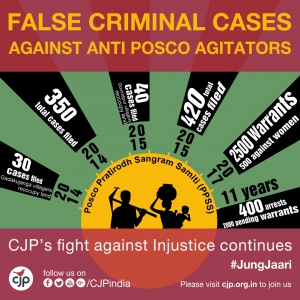

The eight long years of Naresh Kumar’s pre-trial detention are far from an anomaly. The indiscriminate use of special laws has created a situation where the promise of a speedy trial is, more often than not, the exception not the rule. The trajectory of the 2020 Delhi Riots cases continues to haunt public memory, where the infamous 17,000 page FIR 59/2020 charged 18 student activists with instigating communal violence as part of a larger “terror conspiracy.” They were arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), a draconian special law which has bound together the politics of protest with the law’s harshest instruments. As of mid-2025, only six have been released on bail. Not a single charge has, five years down, been framed. A detailed analysis of the incarcerations in this FIR may be read here.

This legal resource traces the jurisprudence on the contradiction between and the incarceration under stringent bail statutes and fundamental right to liberty under Article 21. The judicial trend from Satender Kumar Antil v Central Bureau of Investigation (2022) to Vernon Gonsalves v State of Maharashtra (2023) to the latest decision in Naresh Kumar demonstrates a clear and consistent position: the label of a “special law” does not justify indefinite pre-trial detention. Our analysis demonstrates that the more severe the bail restrictions, the greater the obligation on the State to ensure swift adjudication.

The Constitutional Imperative

“Article 21 is the Ark of the Covenant so far as Fundamental Rights [are] concerned. It deals with nothing less sacrosanct than the rights of life and personal liberty of the citizens of India.”

— Satender Kumar Antil vs Central Bureau Of Investigation (2022)

Article 21 of the Constitution of India reads:

“No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.”

The Apex Court has consistently affirmed the ‘Golden Triangle’ of fundamental rights which sustain and nourish each other[2]: Article 14 (Right to Equality), Article 21 (Right to Life), and Article 19 (Freedom of Speech). Consequently, any legal procedure that deprives an individual of the most fundamental of their rights must be just, fair, and reasonable, that is, a procedure which promotes speedy trial[3]. This principle has been foundational to a series of decisions which establish the right to a speedy trial as implicit in the broad sweep of Article 21.

The Inherent Right to a Speedy Trial

“Arrest is not a draconian measure to be used at the whims of the police officer.”

— Inder Mohan Goswami v. State of Uttaranchal (2007)

That the right to a speedy trial is an integral part of the fundamental right to life and liberty was first enunciated all the way back in 1979. In Hussainara Khatoon v Home Secretary, State of Bihar, the Supreme Court reasoned that for a legal procedure to be just under Article 21, it must ensure “a reasonably expeditious trial” to determine the guilt of an accused. Since then, this ratio has been affirmed and re-affirmed without a single dissenting note.

The Constitutional guarantee was further developed by the Apex Court in A.R. Antulay v R.S. Nayak (1992), which recognised that the violation of this right may even demand the “quashing of a criminal proceeding altogether.” In Uday Mohanlal Acharya v. State of Maharashtra (2001), the Supreme Court observed that the right to ‘default bail’ under Section 167(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) (now Section 187(2) of BNSS) is “nothing but a legislative exposition of the constitutional safeguard under Article 21.” The Bench held that if the accused is ready to furnish bail, and the prosecution has failed to file the charge sheet within the stipulated period, then the former has an indefeasible right to be released on bail. A decade later, the Court in Sanjay Chandra v. Central Bureau of Investigation (2011), recognising the hardship of pre-trial detention, ruled that the act for holding an accused in custody must be based on ‘necessity’ and not ‘punishment.’

Recasting Bail under Special Acts: The Supreme Court’s Mandate

The principles established in these seminal judgments were decisively applied to ‘special acts’ in Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation (2022), which sought to provide clear guidelines for lower courts to give effect to the maxim that ‘bail is the rule and jail is the exception.’

Confronting the crisis of India’s overflowing jails and the “continuous supply of cases seeking bail,” the Supreme Court detailed a comprehensive framework to realign the judicial balance between legislative strictures and individual rights. To enlarge the scope and ease the process of bail, the Court devised a four-fold classification of offences, reproduced below:

- Category A Offences: Punishable with imprisonment of 7 years or less

- Category B Offences: Punishable with death, imprisonment for life, or imprisonment for more than 7 years

- Category C Offences (Special Acts): Punishable under Special Acts containing stringent provisions for bail like NDPS (S.37), PMLA (S.45), UAPA (S.43D(5)), Companies Act, (S.212(6)), etc.

- Category D Offences: Economic offences not covered by Special Acts

Among these, Category C specifically addresses offenses under special acts that contain stringent bail provisions, such as Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA), National Security Act, 1980 (NSA), Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS), and various Gangster Acts.

Significantly, the Court extended the constitutional mandate of a speedy trial to cases under special laws, stating that “the general principle governing delay would apply to these categories also.” The Court added that Section 436A of CrPC (now Section 479 of BNSS), which limits the detention of undertrial prisoners to half of the maximum prescribed sentence, would apply to special acts in the absence of a specific provision to the contrary.

In a pivotal declaration, the Court directly linked the severity of a statute to a heightened obligation for a speedy trial, holding that “more the rigor, the quicker the adjudication ought to be.”

The complete judgment delivered in Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation (2022) can be read here.

The guidelines laid out in Satender Kumar are the culmination of judicial reasoning on special acts which echoes as far back as Shaheen Welfare Association v. Union of India (1996). In that landmark ruling, the Court acknowledged the legislature’s decision to sacrifice some personal liberty for the sake of protecting the community, but stipulated that this very sacrifice makes it “all the more necessary that investigation of such crimes is done efficiently and an adequate number of Designated Courts are set up,” to ensure that “persons ultimately found innocent are not unnecessarily kept in jail for long periods.”

This jurisprudence has continued to evolve through the decades, with P. Chidambaram v. Directorate of Enforcement (2019) cautioning against a “mechanical application of a statute” to deny bail, and Mohd. Enamul Haque v. Enforcement Directorate (2024) holding that prolonged incarceration will “inure to the benefit of the accused for bail” when the delay is not attributable to him.

Read collectively, these cases demonstrate a clear judicial trend: the more severe the statutory bail restrictions, the greater the obligation on the State to ensure a speedy trial, and the more likely that a delay will lead to the accused’s release.

Can Bail be the Exception? The Judicial Approach to Special Laws

The Paradox of Preventive Detention

Aniket is a 24-year-old law student from Madhya Pradesh. On 14 June 2024, he raised his voice against the inappropriate behaviour of a professor towards a female student belonging to a Scheduled Caste. The professor retaliated by assaulting him and registering an FIR against him on a variety of charges, ranging from rioting to attempt to murder.

On recommendation of the Station House Officer and the Superintendent of Police, the District Magistrate charged Aniket with Section 3(2) of the National Security Act. This order of preventive detention was served to him while he was already lodged in Bhopal Central Jail. His representation against the order was rejected by the same District Magistrate who issued the order, and subsequent appeals were dismissed by the Advisory Board and the Madhya Pradesh High Court. Instead, the order was extended thrice, leading to his pre-trial detention for over a year. These extensions were approved despite Aniket being granted bail for the underlying charge all the way back in January 2025.

Aniket filed a Special Leave Petition (SLP) in the Supreme Court, submitting that his alleged offence amounted to nothing more than simple assault and criminal intimidation, charges which have no proximity to demand the draconian measure of preventive detention. The prosecution, however, insisted that the detention was necessary due to Aniket’s “potential to disturb public order.”

The bench of Justices Ujjal Bhuyan and K. Vinod Chandran, aghast at the total “non-application of mind” of the police and lower courts, ruled that his preventive detention under NSA was “wholly untenable.”

The reasoned order by Justice Bhuyan carefully analysed NSA Section 3(2) to conclude that a person can only be taken into preventive detention if his activities are prejudicial to the security of the State, maintenance of public order, or maintenance of essential supplies and services. The Bench observed that the preventive detention order was issued with the intent to prevent the appellant from acting in a manner “prejudicial to the maintenance of law and order.” This, however, is a much broader ambit than “public order” which requires an impact to “the community or the public at large” (Ram Manohar Lohia v State of Bihar, 1965). The inability of the police to handle a law and order situation cannot be an excuse to invoke preventive detention (Nenavath Bujji v State of Telangana, 2024).

Reprimanding the authorities, the Court observed that “the entire intent appears to continue the detention of the appellant since he was likely to get bail in the criminal case, which, in fact, he got.” However, preventive detention is not intended to deny rightful bail to an accused charged with a regular criminal offence. The Apex Court ruled that:

“Preventive detention being a hard law, it is axiomatic that an order of preventive detention should be strictly construed. It is the duty of a constitutional court like the High Court to minutely scrutinize an order of preventive detention to ensure that the order of preventive detention squarely falls within the four corners of the relevant law and that the liberty of a person is not unlawfully compromised.”

The reasoned order in Annu @ Aniket Through His Father As Next Friend Krupal Singh Thakur v. Union of India (2025) may be read here.

The UAPA Conundrum: Reclaiming Judicial Discretion from Statutory Veto

Within the landscape of India’s special laws, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act occupies a uniquely terrifying position. Enacted in the same year as Naxalbari peasants’ uprising, the Act’s stated purpose is to prevent unlawful and terrorist activities which are prejudicial to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the State. But overbroad definitions, sweeping investigative powers, and impossibly stringent bail provisions have transformed the legislation into an instrument of terror itself – whereby suspicion becomes conviction and pre-trial detention becomes punishment.

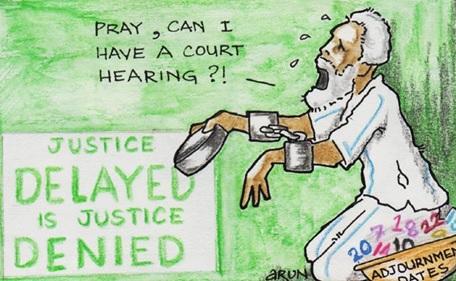

Cartoon by Arun Ferreira | Source: Colours of the Cage

The human cost of this statute is staggering. Based on the data from the National Crime Records Bureau, 8,136 persons were arrested under the UAPA from 2015 to 2020. A mere 2.8% were convicted.[4]

With the vast majority of cases ending in acquittal or withdrawal, bail becomes the only remedy that stands between an individual and a decade in jail without trial. However, Section 43D(5) of the Act has turned the oft-quoted maxim over on its head – making jail the rule and bail the exception.

Section 43D(5) reads:

“Notwithstanding anything contained in the Code, no person accused of an offence punishable under Chapters IV and VI of this Act shall, if in custody, be released on bail or on his own bond unless the Public Prosecutor has been given an opportunity of being heard on the application for such release:

Provided that such accused person shall not be released on bail or on his own bond if the Court, on a perusal of the case diary or the report made under section 173 of the Code is of the opinion that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accusation against such person is prima facie true.”

In simple terms, Section 43D (5) forbids the Court from granting bail if the prosecution makes out a preliminary case. The defence, at this stage, is at a significant disadvantage: it can neither submit exculpatory evidence of its own, nor cross-examine the prosecution’s evidence. When judicial discretion is replaced by a prosecutorial veto, how, then, is a Court to grant bail?

The Supreme Court’s judgment in NIA v. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali (2019) is the starting point for the modern jurisprudence on this question. The Court overruled a bail order granted to the accused by the Delhi High Court, stating that its analysis “[bordered] on being perverse, as it has virtually conducted a mini trial…and even questioned the genuineness of the documents relied upon by the Investigating Agency.” The judgment placed extraordinary weight on the accusatory narrative of the police and practically barred trial courts from examining the merits and demerits of the evidence.

The Court held that:

- Statutory mandate of a prima facie assessment requires a lighter degree of satisfaction. The evidence collated by the investigating agency must be presumed true.

- At the bail stage, courts must not engage in a “detailed analysis of evidence” or discard any material being placed before it as inadmissible.

The Watali judgement has cast a long shadow over the evolution of bail jurisprudence under the UAPA, widely and often blindly cited by High Courts in several bail rejection orders. It not only cements the “jurisprudence of suspicion,” but equates the degree of satisfaction required to reject bail to the level of the one necessary to frame charge[5].

Such an interpretation of ‘prima facie true’ criteria raises a fundamental contradiction: if the allegations of the investigative agency are to be taken at face-value, what is the need or purpose of the Judiciary?

Union of India vs K.A. Najeeb (2021) offers a modest pushback[6]. The case involved an accused who had been incarcerated for more than five years, without a trial even having commenced. Relying on the ratio of Shaheen Welfare Association, the Kerala High Court held that such protracted incarceration violates the respondent’s right to speedy trial and access to justice, regardless of limitations under special enactments. The State’s appeal relied on Watali to argue that the High Court erred in granting bail without adhering to the statutory rigours of Section 43D(5).

The Apex Court dismissed the appeal, holding that:

- Section 43D (5) is not the sole metric, but “merely…another possible ground” for the Court to deny bail. It is to be considered alongside factors like gravity of the offence, possibility of evidence or witness tampering, chance of absconsion, etc.

- The rigours of a provision like Section 43D (5) will “melt down where there is no likelihood of trial being completed within a reasonable time and the period of incarceration already undergone has exceeded a substantial part of the prescribed sentence.”

Read a detailed comparative analysis of Watali and Najeeb here.

Though the Najeeb ruling partially reads down the ‘prima facie true’ argument, it refrains from confronting Watali head-on, finding that the latter deals with an “entirely different factual matrix.” A direct challenge appears for the first time in Vernon vs State of Maharashtra (2023).

Trade unionist Vernon Gonsalves and Advocate Arun Ferreira were two of the accused in the Bhima Koregaon case. Based upon a combination of inferences drawn from letters in the nature of hearsay, statements from ‘protected witnesses,’ and third-party communication, the Prosecution wove a narrative alleging that the two were part of a ‘conspiracy’ to overthrow the State.

In granting their bail application, Supreme Court Justices Aniruddha Bose and Sudhanshu Dhulia recalibrated the standard set in Watali. The Court held that:

- A “surface-level analysis of the probative value of evidence” is essential when assessing whether the case is prima facie true under Section 43D (5) of UAPA.

- Though an ordinary bail petition precludes a scrutiny of evidence, the “restrictive provisions” of Section 43D (5) make “some element of evidence-analysis…inevitable.”

Affirming the guideline in Satender Kumar Antil, the Court ruled that “when the statutes have stringent provisions the duty of the Court would be more onerous. Graver the offence, greater should be the care taken to see that the offence would fall within the four corners of the Act.”

The Court also acknowledged Najeeb noting that at the time of the judgment, the accused had spent five years in jail, while further clarifying Article 21 can be invoked due to prolonged incarceration, even if the period is less than half of the maximum sentence.

By requiring courts to assess some believability in the evidence (and not merely its existence), the Vernon ruling opens the door for meaningful judicial engagement at the bail stage[7].

The complete judgment delivered in Vernon vs State of Maharashtra (2023) can be read here.

Advocate Gautam Bhatia’s analysis of the jurisprudence on bail under UAPA, culminating in Vernon, distils three judicial principles[8]:

- The definitional clauses of the UAPA must be given a strict and narrow construction.

- The allegations in the chargesheet must be individualised, factual, and particularistic.

- Bail cannot be denied when the Prosecution’s evidence is of “low probative value.”

However, the jurisprudence on this point remains ambiguous. Since Watali, Najeeb, and Vernon were delivered by benches of equal strength, lower courts are free to selectively rely on either approach. The Delhi High Court, for instance, has had multiple opportunities to apply Vernon and Najeeb in the context of FIR 59/2020, but has betrayed a caution verging on abstention[9].

While we wait for the Supreme Court to explicitly resolve this interpretive conflict, Professor Hany Babu and Advocate Surendra Gadling (two other accused in the Bhima Koregaon case who continue to be in pre-trial detention) present an elegant argument[10] which may lift the ominous shadow of Watali. A close reading of Section 2 (d) of UAPA defines “Court” as a criminal court with jurisdiction to try offenses under the Act. This means that the restrictions on bail in Section 43D (5) were intended to apply only to trial courts, and not to constitutional courts.

Such an interpretation renders Watali per incuriam, and frees Constitutional Courts from the statutory constraint altogether – restoring the power of the Constitutional promise of liberty to override a statutory bail provision, no matter how special the law.

Stringency and Snails: The PMLA Recalibration

In the lead-up to the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act was shrewdly maneuvered to disrupt the electoral playing field. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) initiated raids on a number of prominent opposition figures, including Hemant Soren (Jharkhand Mukti Morcha), D.K. Shiva Kumar (Indian National Congress), and Abhishek Banerjee (All India Trinamool Congress). In the high-profile ‘Delhi Liquor Scam’ case, the arrests of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal (Aam Aadmi Party) and K. Kavitha (Bharat Rashtra Samithi party) came in step with the Election Commission’s announcement of the Lok Sabha poll schedule.

The arrests brought two recurring themes into popular discourse: the weaponisation of the ED’s powers of arrest, and the draconian nature of the PMLA’s bail conditions.

The first of these finds its roots in Section 19 of the PMLA, which grants ED officials the power to arrest individuals if they have “reason to believe” that a person is “guilty of an offence punishable under this Act.” The Supreme Court in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary v. Union of India (2022) upheld this provision, reasoning that unlike police officers who are only tasked with investigating offences, ED officers have an added responsibility to “prevent” money laundering. Operating under the PMLA as a ‘special’ investigative agency, the ED is exempt from many procedural safeguards and oversight mechanisms that apply to the police under BNSS. By vesting the power to arrest entirely within the ED’s internal hierarchy without prior judicial sanction, the provision allows the agency to be the sole judge of its own “reason to believe.”

The second concerns the twin bail conditions under PMLA. Section 45(1) of the Act reads:

“Notwithstanding anything contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, no person accused of an offence under this Act shall be released on bail or on his own bond unless:

(i) the Public Prosecutor has been given an opportunity to oppose the application for such release; and

(ii) where the Public Prosecutor opposes the application, the Court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that he is not guilty of such offence and that he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail”

In 2017, the two-judge Bench in Nikesh Tarachand Shah v Union Of India had struck down an earlier version of Section 45(1), holding that it inverted the presumption of innocence. The Parliament amended the provision in 2018, replacing the offence threshold with the phrase “under this Act” but retaining the twin conditions. A subsequent challenge to the amendment in Vijay Madanlal was rejected by the Court, which held that the revised provision is “reasonable” and has a “direct nexus” with the purpose of the PMLA.

In “deferring to the wisdom of the Parliament” and upholding the constitutionality of Section 45 (1), Section 19, and several other contested provisions of the PMLA, the judgment in Vijay Madanlal entrenches a legal architecture that cements the unfettered powers of the ED while severely restricting the grant of bail[11].

However, the stringent statutory framework upheld in Vijay Madanlal was soon confronted with the practical realities of indefinite incarceration. Subsequent decisions reveal a recalibration, with the judicial trend deferring to the right to liberty in the face of prolonged proceedings.

The Constitutional imperative of a speedy trial was the fulcrum for granting bail to former Deputy Chief Minister of Delhi Manish Sisodia, arrested in the Delhi liquor policy scam in February 2023. The Supreme Court noted the ‘snail’s pace’ of the proceedings[12] (17 months without trial commencement) and the scale of the case (493 witnesses, thousands of pages of records and over a lakh pages of digitised material), making near-term completion unrealistic. Reinforcing the ratios of Sanjay Chandra, which emphasised the ‘necessity’ test, and Satender Kumar Antil, which mandated Article 21 protections for Category C offences, the Court ruled that bail is not to be withheld as a punishment. “The reason is that the constitutional mandate is the higher law, and it is the basic right of the person charged of an offence and not convicted, that he be ensured and given a speedy trial,” wrote (now, Chief) Justice B.R. Gavai.

The complete judgment in Manish Sisodia v Directorate of Enforcement (2024) can be read here.

Arvind Kejriwal v. Directorate of Enforcement (2024) further expanded the scope of judicial scrutiny at the bail stage. It held that “all material and evidence that can be led in the trial and admissible, whether relied on by the prosecution or not, can be examined,” since guilt “can only be established on admissible evidence to be led before the court.” Recognising that the ED’s power of arrest under the PMLA constitutes a drastic curtailment of liberty under Article 21, the Court emphasised that the Special Court must “independently apply its mind, without being influenced by the opinion recorded in the ‘reasons to believe.’”

The bail order in Arvind Kejriwal v. Directorate of Enforcement (2024) can be read here.

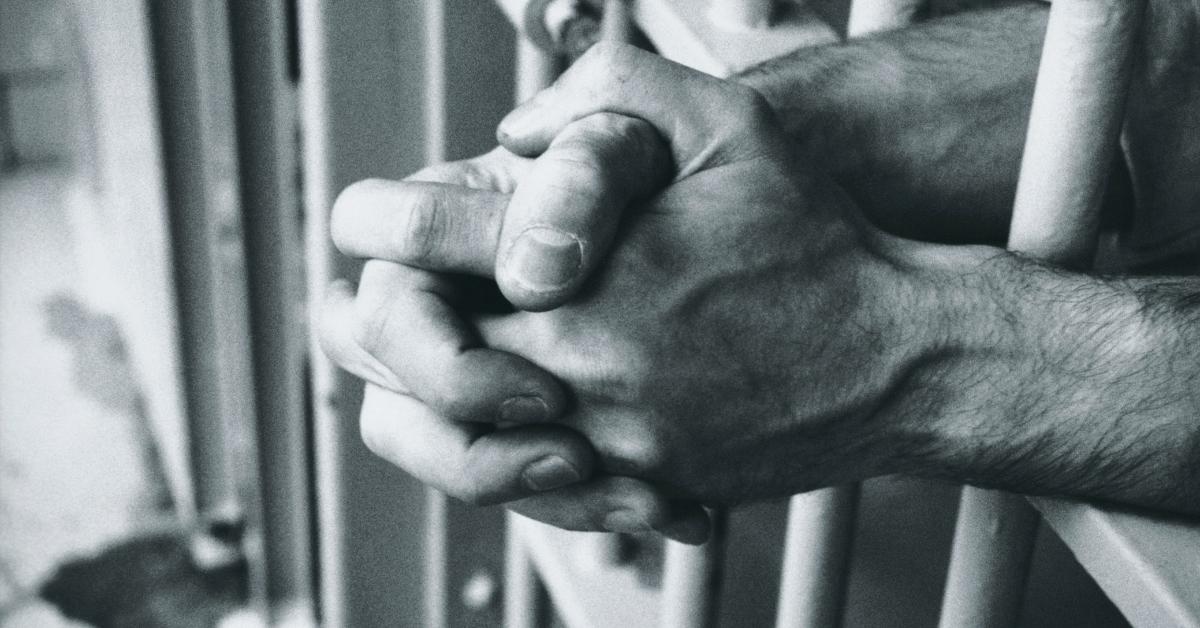

The Human Cost of Procedural Delay

Mohd. Muslim was 23 years old when he was arrested under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, a drug trafficking case involving 180 kilograms of ganja. Though he was not found in possession of any narcotic drugs (his name having surfaced only in a co-accused’s statement), he was charged with the production, possession, and criminal conspiracy in a drug offence. By 2023, he had spent over seven years in prison with the trial barely at its halfway stage.

Section 37 of the NDPS Act restricts the grant of bail through twin conditions similar to the PMLA. It requires that the court records its satisfaction that the accused might not be guilty of the offence and that upon release, they are not likely to commit any offence. In Mohd. Muslim v. State (NCT of Delhi), the Court observed that the Section 37 requirement to be “satisfied” of the twin conditions can only mean a “prima facie determination,” since all evidence is not yet before the court. It reasoned that a literal or mechanical reading would leave judicial discretion “within a very narrow margin,” effectively excluding bail altogether and amounting to punitive detention. To remain within constitutional limits, the Court stressed that this prima facie assessment must be applied “reasonably” based on the materials available at the time of the bail hearing.

The judgment further clarified that undue delay in trial is an independent ground for bail in light of Section 436A CrPC (Section 479 BNSS), which is not fettered by Section 37. Holding that prolonged incarceration, particularly where the delay is not attributable to the accused, must weigh heavily in favour of release regardless of the gravity of the alleged offence, the Court granted bail.

Before parting, the Court reflected on special laws and their stringent bail conditions, warning that if trials are not concluded in time, then the “injustice wrecked on the individual is immeasurable.” Drawing from A Convict Prisoner v. State of Kerala (1993), it recognised imprisonment as a “radical transformation” whereby the prisoner completely loses his identity: known by a number, stripped of personal possessions and relationships, engulfed by psychological scars from a complete loss of freedom, status, and dignity. The impact is especially acute for those from the weakest economic strata, where detention means an immediate loss of livelihood, disintegration of family, and alienation from society. The judgment stressed that courts must remain sensitive to these irreparable harms and ensure that trials, particularly under special laws with stringent bail thresholds, are taken up and concluded with urgency.

The judgment delivered in Mohd. Muslim v. State (NCT of Delhi) (2023) can be read here.

The Long Wait for Justice

Across four decades of jurisprudence, Constitutional Courts from Naresh Kumar to Vernon Gonsalves to Manish Sisodia have articulated a consistent judicial trend: the Constitution does not carve out exceptions to liberty simply because a statute is labelled “special.” The more severe the bail restrictions, the greater the obligation on the State to ensure a swift and fair adjudication.

The key principles accepted by the judiciary to grant bail in special statutes are outlined below:

- Undue Delay as a Constitutional Trigger: Prolonged pre-trial detention is a direct violation of the right to liberty under Article 21. Even under special laws with stringent bail provisions, undue delay in trial, particularly when not attributable to the accused, in trial is per se a valid bail ground for securing bail.

- The ‘Prima Facie’ Contradiction”: A mechanical interpretation of the statutory condition that a court must be ‘prima facie’ satisfied of an accused’s innocence would make bail illusory. Courts must apply a reasonable interpretation of this condition, avoiding a pre-emptive determination of guilt and ensuring the presumption of innocence is not inverted.

- Scrutiny of Evidence: While avoiding a mini-trial, courts must exercise meaningful scrutiny of evidence at the bail stage. Special courts must demonstrate an independent application of mind, free from the influence of prosecuting and investigative agencies, to assess whether the material has some probative value. Guilt can only be established on admissible evidence.

- “Graver the offence, greater the scrutiny”: An order of preventive detention should be strictly construed. It is the duty of a constitutional court to ensure that such an order falls squarely within the four corners of the relevant statute.

- Length of Detention: The mandate to grant bail when an undertrial has served half the maximum possible sentence (BNSS Section 479) applies equally to special laws, unless expressly excluded. Under Article 21, prolonged incarceration can itself justify bail, even if the period served is less than half the maximum sentence.

- “Constitutional mandate is the higher law.” The judiciary’s ultimate deference is to the supremacy of the Constitution. The constitutional mandate of Liberty is the highest law of the land, and must unequivocally trump any and all statutory restrictions.

“In a democracy, there can never be an impression that it is a police State as both are conceptually opposite to each other” (Satender Kumar Antil).

Inside the courtrooms, judges may eloquently espouse democratic ideals as counsel spar over whether Article 21 is an administrative indulgence. But on the outside, the endless adjournments of the bail hearings for Surendra Gadling, Hany Babu, Sharjeel Imam and Gulfisha Fatima, among countless others incarcerated under ‘special laws’, betray a different reality. Alongside with the sweeping, often unchecked, powers of agencies like the NIA and ED, the ‘impression’ continues to tilt uncomfortably towards indefinite preventive detention masquerading as prosecution.

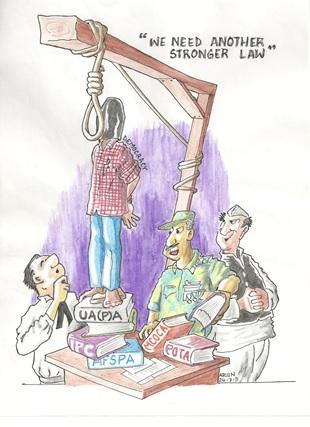

Cartoon by Arun Ferreira | Source: Colours of the Cage

The promise of a speedy trial has emerged as the judiciary’s primary safeguard against indefinite detention under draconian statutes. But a safeguard that is invoked only after years of confinement or ladders of appeals is no safeguard at all. The Constitutional imperative demands that it must be enforced with unflinching consistency, from the highest constitutional courts to the lowest trial courts, and the burden must be on the State to justify every continued moment of incarceration.

(The legal research team of CJP consists of lawyers and interns; this legal resource has been worked on by Raaz)

Footnotes

[1] Now, under Section 479, the provision of granting bail to under trial prisoners will now be limited to those undertrials who are first-time offenders if they have completed one-third of the maximum sentence. Since charge sheets often mention multiple offences, this may make many under trials ineligible for mandatory bail. Furthermore, through the said provision, the prohibition of getting bail under the said section had also been expanded to those offences that are punishable with life imprisonment. Therefore, the following under trials are barred from applying for statutory bail under the said section if: offences punishable by life imprisonment, and persons who have pending proceedings in more than one offence.

[2] Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee v Union of India (1994)

[3] Union of India v K.A. Najeeb (2021)

[4] ‘UAPA: Criminalising Dissent And State Terror’(People’s Union of Civil Liberties, September 2022)

[5] ‘When Najeeb meets Watali – On the statutory restrictions on grant of bail under UAPA’ (Hany Babu and Surendra Gadling, Issues in Constitutional Law and Philosophy, 2025)

[6] ‘Bail under UAPA: Does the new SC judgment offer a ray of hope?’ (Sanchita Kadam, Citizens for Justice and Peace, 2021)

[7] ‘How the Delhi riots case remains stagnant with close to a dozen student leaders incarcerated’ (SabrangIndia, 2025)

[8] ‘Recovering the Basics: The Supreme Court’s Bail Order in Vernon Gonsalves’ Case’ (Gautam Bhatia, Issues in Constitutional Law and Philosophy, 2023)

[9] Supra, 7

[10] Supra, 5

[11] ‘Challenges to the Prevention of Money Laundering Act | Judgement Summary’ (Sushovan Patnaik, Supreme Court Observer, 2024)

[12] ‘“A game of snake and ladder”: Tracing Manish Sisodia’s 17-month journey to bail’ (Sushovan Patnaik and Advay Vora, Supreme Court Observer, 2024)