Delhi Riots 2020: Stalled justice & the architecture of indefinite detention, FIR 59/2020 in perspective Five years without bail: FIR 59/2020 and the Delhi Riots cases expose a pattern of procedural lapses and prolonged incarceration of student activists and a politician

01, Jul 2025 | CJP Team

There are cases where delay feels procedural, and then there are cases where delay becomes the punishment itself. To use a cliché, the process is the punishment. FIR 59/2020 is no ordinary criminal proceeding. It is a study in how the machinery of justice, even when questions of personal liberty are involved, can end up incarcerating without trial, and accusing without resolution. Under the expansive shadow of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), the line between protest and conspiracy has been blurred, perhaps deliberately. And in the half-decade since its registration, this case has revealed how the legal process, when even the constitutional courts fail to adequately respond, can start to resemble indefinite detention by another name.

Protest, conspiracy, and the mechanics of delay

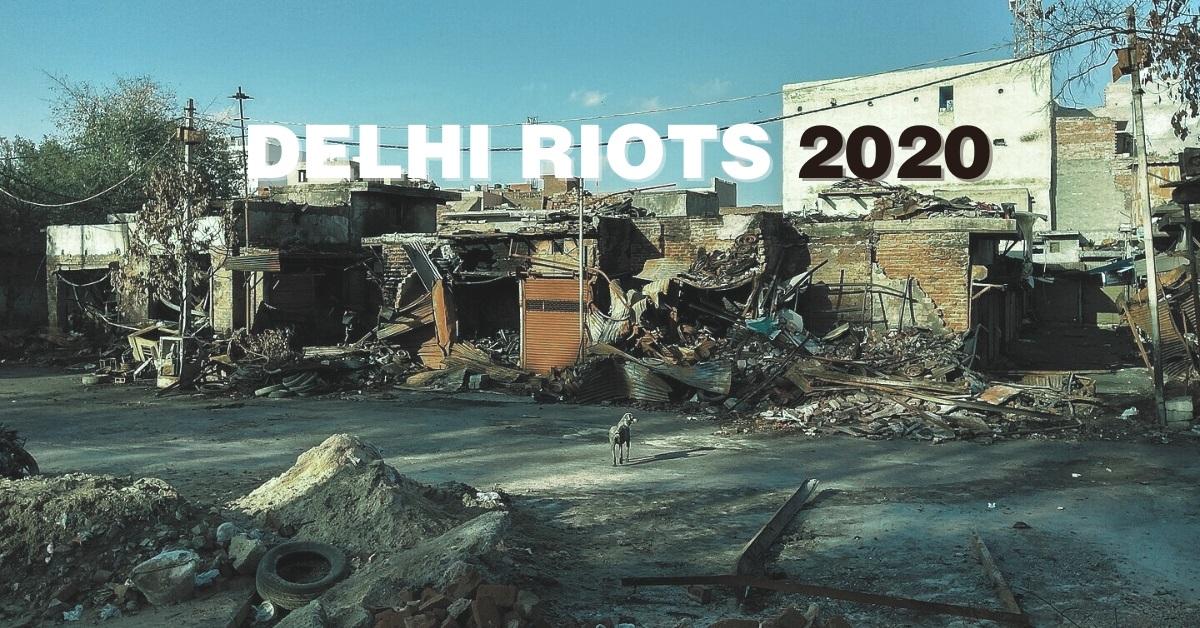

In February 2020, as nationwide protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) intensified (see detailed ground report by Sabrang India), Delhi found itself engulfed not merely in political dissent, but in targeted violent communal conflagration. What began as vibrant rights’ based protests to assert constitutional rights and freedoms through parallel sit-ins and road blockades soon deteriorated –with the active election-driven hate campaigns of the right-wing – into three days of bloodshed across North-East Delhi, leaving 53 people dead, hundreds injured, and entire neighbourhoods reduced to ashes. The human toll was staggering—but what followed, in parallel, in the courts, was, in many ways, just as consequential. Two and a half years after the violence, a Citizens Inquiry Committee Consisting of Retired Judges severely indicted right-wing driven hate speeches and their amplification by an uncritical electronic media for the escalation.[1]

On March 6, 2020, (18 days before the NDA regime declared a nationwide lockdown on March 24) the Delhi Police’s Special Cell registered FIR 59/2020, alleging a “larger conspiracy” behind the riots. The charge sheet, filed on September 16, 2020, stretched over 17,000 pages, and wove together disparate acts of protest, civil disobedience, WhatsApp conversations, speeches, and financial transactions as the basis of an expansive narrative of terror conspiracy. Key provisions invoked included Sections 120B (criminal conspiracy), 302 (murder), and 153A (promoting enmity) of the Indian Penal Code, as well as several sections of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967.

The UAPA designation was not incidental. It allowed the prosecution to sidestep conventional bail safeguards and extend pre-trial detention far beyond the thresholds permissible under the ordinary Criminal Law and Procedure. Over time, the 18 accused (mostly student leaders and activists), including Dr Umar Khalid, Devangana Kalita, Natasha Narwal, Asif Iqbal Tanha, Safoora Zargar, and Sharjeel Imam were arrested under the FIR. While some were already in custody in related cases, FIR 59/2020 became the prosecution’s keystone, binding together the politics of protest with the law’s harshest instruments. Khalid had been granted bail by ASJ Yadav on April 15, 2021, the order noting that he cannot be incarcerated on the basis of sketchy material. However, he remains in jail –after being arrested on September 14, 2020 under stringent UAPA charges for ‘being part of a larger conspiracy in the north east Delhi violence case of 2020.’

For rights activists, advocates and academics too, it is crucial to note that that the initial FIR (which speaks of the conspiracy by Umar Khalid and his ‘speeches’) did not even contain non-bailable offences let alone offences under the draconian UAPA. It is only after the initial set of arrested accused were released by the Magistrate on bail –were a set of non bailable offences were added. At that point of time there already existed 750 FIRs for the different instances of violence and destruction of property and this FIR 59 was in addition to the same. Safoora Zargar was arrested in one of the 751 FIRs and was granted bail within a day of two in the earlier offences. Before she could actually be even released from jail –the Delhi Police –in what a clear case of over reach and malice—arrested Safoora (who as mentioned above did not even find mention in FIR 59) by adding offences under the stringent UAPA. This demonstrates that the purpose of the executive (prosecution) was to simply keep the student activists in jail, no matter what. Given that these were initial developments that had been called out by the defence in Court, the judiciary itself ought to have called this substantive and procedural injustice out.

As of mid-2025, not a single charge has been framed. The trial has remained frozen in its pre-charge phase for nearly five years. This extended inertia cannot be explained solely by the complexity of evidence. A significant part of the delay stems from what can only be described as judicial instability. The case has passed through multiple benches, with judges being reassigned, transferred, or rotated mid-way through critical proceedings. This institutional churn, as much as the statute books themselves, has shaped the case’s glacial pace and rendered a timely trial ever more elusive.

The calumny of calling out ‘delays’ by the defence

While at every bail hearing, virtually, accused rights defenders and their counsel have called out how the prosecution has (in a bid to bias the court and public opinion) sought to blame the defence for “delay”, even this tactic has been called out in court. Student activist, Khalid Safi has presented a detailed analysis of the delay in which he has demonstrated to the court that the delay is and has been only on account of a) the Prosecution; b)Judicial officers being unable to devote time and, c) the prosecution itself having sought and obtained a stay on the proceedings in order to contend that they would not make available the physical copy of the Final Reports / Charge sheets to the incarcerated accused, a contention which flies in the face of basic principles of natural justice. How are incarcerated accused supposed to read 17000 pages in a charge sheet, without reasonable time to study these once they are provided, is the question asked? Even if some time (and adjournments) by defence counsel are sought in the course of five long years, how can the plea for bail be ever resisted on that ground? Especially when the incarcerated accused have not in any manner gained from such delay. The delay has only prolonged their jail custody!

High cost of exercising fundamental freedoms

Of the total accused in the case, one, Tahir Hussain, is a politician and a former corporator. The rest, student activists and leaders protesting the anti-constitutional CAA 2019-NRC: Dr. Umar Khalid, Khalid Saifi, Ishrat Jahan, Meeran Haider, Gulfisha Fatima, Shifa-Ur-Rehman, Asif Iqbal Tanha, Shadab Ahmed, Tasleem Ahmed, Saleem Malik, Mohd. Saleem Khan, Athar Khan, Safoora Zargar, Sharjeel Imam, Faizan Khan, and Natasha Narwal. Of the 18 named in the FIR, only six have been released on bail. Those are: Ishrat Jahan, Mohammad Faizan Khan, Safoora Zargar, Natasha Narwal, Devangana Kalita, and Asif Iqbal Tanha. Even qua their (alleged) role in protests, a study of the charges reveals that there is no distinction that can be made between the roles of those human rights defenders (accused) who are in custody and those (already) granted bail. What is more important is, that not a single act of violence, recovery of weapons, speech resulting in incitement, or call for violence can be attributed to them. This obvious lacunae is sought to be inserted or peppered in by belated third party statements which do not lead to recoveries (of such weapons) or connection to the rest of the 751 FIRS. Significantly, by the time the violence erupted in Delhi, Sharjeel Imam was in custody already (having been arrested on January 28, 2020 and Umar Khalid was not even present in Delhi when the violence took place.

Hence, ten Muslim student activists/human rights defenders—one woman and eight men, many of them bright youth leaders–are facing “charges of terrorism” in the 2020 Delhi riots conspiracy case are enduring serious and questionable systemic failures in their judicial quest for bail. Judgements have been reserved while and after Judges have been transferred and hearings inexplicably delayed. Several of the petitions have been pending for several months in the Delhi high court.

One woman, Gulfisha Fatima and nine men– Dr Umar Khalid, Saleem, Sharjeel Imam, Abdul Khali Saifi, Meeran Haider, Salim Malik, Shifa Ur Rehman, Shadab Ahmed and Athar Khan – are those so unjustly incarcerated. Although a special bench consisting of Justice Siddharth Mridul and Justice Rajnish Bhatnagar listed the nine bail petitions for hearing between 34 and 60 times since April 2022 and even concluded hearings and reserved judgements in six between January and March 2023 – petitions of Saifi, Fatima, Haider, Malik, Rehman, and Saleem – it failed to deliver a final judgement.

Gulfisha Fatima who was arrested in April 2020 – two months after the Delhi riots has had an excruciatingly gruelling challenge to get bail. The bench comprising Justices Mridul and Bhatnagar had reserved its order on her bail application on February 13, 2023—a good nine months after she filed an appeal against a Delhi court’s refusal to grant her bail in March 2022! As if this were not enough, then came the double whammy when, on July 5, 2023, the Supreme Court collegium recommended Justice Mridul’s transfer to the Manipur high court as its chief justice – which the Union government cleared three months later on October 16 – and a little more than a month later, Justice Bhatnagar’s transfer to the Rajasthan high court. A new bench of Justice Suresh Kumar Kait and Justice Shalinder Kaur was then scheduled to hear the nine cases afresh, further prolonging incarceration. On November 1, 2023, Justices Kait and Kaur fixed dates for re-hearings thereafter in January and February the next year, 2024. Barely had this happened was the announcement of the judicial elevation of one of the judges, Justice Suresh Kumar Kait as Chief Justice of the High Court of Madhya Pradesh with effect from September 2024!! Now, the matters lie before the bench of Justice Navin Chawla and Shailender Kaur.

The Amitabh Rawat phase: bail, paperwork, but no charge hearings

In the initial years of the case, Additional Sessions Judge (ASJ) Amitabh Rawat became closely associated with the 2020 riot-related UAPA matters. Sitting at the Karkardooma District Court, ASJ Rawat presided over several procedural applications and bail hearings, including the rejection of Umar Khalid’s bail under the Delhi Riots Conspiracy FIR in March 2022, in an order running over 40 pages that leaned heavily and only on the prosecution’s narrative. Khalid had put up a rigorous and detailed defence through advocate Trideep Pais arguing that there were 750 FIRs registered before February 28, 2020 and the FIR 59/2020 (UAPA conspiracy case), that implicates Umar was registered on March 6, 2020. He argued that there was no occasion or event to register FIR 59/2020 and nobody should have been arrested under it. “The charge sheet filed before conclusively shows that there was no crime disclosed when the complaint was made”, he said. Secondly, Adv Pais had pointed out that the police relied on the speech from a YouTube clip used by news agencies (News 18 and Republic TV), and not the entire speech delivered by Khalid in Amravati, Maharashtra. He added that when the news channels were asked by the police to provide the source of the speech, they said that they relied on a tweet made by Amit Malaviya. More details of the previous hearings may be read in this SabrangIndia report. (Amit Malviya heads the Bharatiya Janata Party’s notorious IT cell and dubs himself National In-charge of BJP’s Information & technology division).

What is crucial to iterate –is how arguments on charge—i.e., whether there exists sufficient evidence to proceed with a trial in FIR 59/2020– had not even begun during the period that ASJ Rawat was hearing the case. Between 2020 and 2023, the case lingered in a kind of procedural purgatory. Defence counsel frequently complained of non-supply of documents, prosecution delays, and the overwhelming volume of evidence. In reality, much of the delay was structural.

In 2023, ASJ Rawat was transferred. That transfer, like many others in the Delhi judiciary, was part of an administrative reshuffle ordered by the Delhi High Court—routine, unremarkable, and yet, in this case, consequential.

The Bajpai phase: a brief flicker of momentum

Judge Rawat’s successor, ASJ Sameer Bajpai, took over and finally initiated arguments on charge in FIR 59/2020 in September 2023. It was the first real procedural movement in over three years. The prosecution, led by the Special Public Prosecutor, opened with oral arguments on the alleged chain of events, the documentary and electronic evidence, and the roles ascribed to each accused. These arguments spanned several months and were concluded by early 2024.

Between October 2023 and March 2024, five defence teams also completed their arguments on charge, contesting the admissibility, interpretation, and weight of the evidence. Some submissions focused on the unreliability of protected witness statements, while others attacked the temporal inconsistencies in the police narrative. At last, it seemed that the case was approaching the critical moment when the court would decide whether to frame charges and commit the accused to trial.In the period when the matter was before Bajpai, on May 28, 2024, he had declined bail to Dr Umar Khalid on the ground noting that “no ‘deep analysis’ of the facts of the case can be undertaken at this stage.[2] Then, just as the matter appeared to turn a procedural corner, it slipped back.

May 2025: Bajpai’s transfer

On May 30, 2025, the Delhi High Court issued a routine transfer order affecting 135 judicial officers, including ASJ Bajpai. He was posted out of Shahdara, where the UAPA-designated court was situated, and reassigned to a fast-track court in Saket. In his place came ASJ Lalit Kumar.

ASJ Kumar, upon assuming charge, directed on June 2 that arguments on charge must begin afresh. The logic, presumably, was that he had not heard the earlier submissions, and a judge cannot rely on oral arguments presented to another. That may be legally sound, but it placed defence lawyers, many of whose clients had already spent four to five years in pre-trial detention, back at square one. Their submissions, objections, and detailed rebuttals would now need to be repeated. While the prosecution, too, would have to reargue a 17,000-page brief.

This reset triggered public outrage. A few lawyers remarked, off the record, that the process resembled “litigating in a loop.” The wheel was being reinvented, they said, just as it had begun to move.

A rare act of introspection: The High Court reverses course

In an unusual gesture that revealed both institutional awareness and tacit acknowledgment of error, the Delhi High Court revoked Bajpai’s transfer on June 19, directing that he return to the UAPA-designated court from July 1. The order stated that in view of the advanced stage of arguments, and the complexity of the material involved, judicial continuity was paramount.

This reversal was not merely administrative, but a quiet admission that the justice system had come perilously close to collapsing under its own bureaucracy. While defence and prosecution lawyers alike welcomed ASJ Bajpai’s return, they also knew that the damage could not be entirely undone.

At any rate, the institutional volatility on display in FIR 59/2020 has not been unique to this case, but its consequences here are particularly acute. The accused are not free on bail, as many remain in custody under a preventive detention regime that forecloses easy release. The charges involve allegations of terrorism, which, under Section 43D(5) of UAPA, make bail nearly impossible unless the court can prima facie reject the prosecution’s theory—a standard that demands more than mere reasonable doubt. In such a context, delays are not procedural inconveniences, but become carceral sentences in and of themselves. However, despite these stringent legal hurdles, it needs recall, that the same Delhi high court that has refused bail in ten cases (11 including Tahir Hussain) did grant bail to three student activists, Asif Tanha, Natasha Narwal and Devangana Kalita in June 2021, a year after their incarceration, looking at the same evidence under UAPA charges and making conclusive and creative interpretations on definitions of how legitimate protest cannot be interpreted, under a stringent anti-terror law as ‘act/acts of terrorism’.

Disruptions, duration, and separate interventions

Nearly 1,825 days have elapsed since FIR 59/2020 was lodged. The charge sheet was filed within six months (Sept 2020), but the trial court did not begin substantive charge‑arguments until September 2023, a gap of three years. Between then and the May 2024 transfer, roughly 40 sessions saw prosecution and defence arguments but those efforts were effectively nullified by judicial transfers and reshuffle.

Alongside trial delays, bail hearings have languished in similar fashion. A subset of eight accused — Sharjeel Imam, Meeran Haider, Khalid Saifi, Gulfisha Fatima, Shifa‑ur‑Rehman, Shadab Ahmed, Athar Khan, and Mohammad Saleem Khan have their bail pleas pending before the Delhi High Court since mid‑2022. Analysis and reporting by Scroll and CourtPractice shows:

| Accused | Bail Plea Filed | Hearings Listed | Benches Involved | Orders Reserved But Not Delivered |

| Sharjeel Imam | April 2022 | 64 | 7 | − |

| Meeran Haider | May 2022 | 72 | 7 | Yes |

| Khalid Saifi | May 2022 | 61 | 6 | Yes |

| Gulfisha Fatima | May 2022 | 67 | 6 | Yes |

| Shifa‑ur‑Rehman | June 2022 | 70 | 7 | Yes |

| Shadab Ahmed | Nov 2022 | 52 | 6 | – |

| Athar Khan | Dec 2022 | 45 | 6 | – |

| Mohammad Saleem Khan | May 2022 | 70 | 8 | Yes |

These pleas have been listed, on average, 60–70 times each. Despite multiple benches finishing oral arguments, no orders have been delivered in most cases. Many listings were cancelled because:

- The special benches failed to assemble (44 occasions for Imam alone).

- Judges were unavailable due to workload or roster conflicts.

- Local administrative notes commonly record “bench did not assemble”.

Haider’s plea was listed 60 times, but heard only 9 times; similar lags affected others.

Justice Mridul & Bhatnagar bench’s involvement in several cases (Haider, Fatima, Saifi, Meeran, Ahmed, Athar) with orders reserved only to be derailed when Justice Mridul was transferred (Nov 2023); the pleas were withdrawn and re‑heard from scratch by a new bench.

The net effect: accused who had been in custody for over four years found themselves awaiting bail hearings under the same substantive arguments reargued all over again.

Several accused have sought higher‑court recourse. For instance:

- Sharjeel Imam filed a writ plea under Article 32 in the Supreme Court (Oct 2024), asking for expedited hearing of his Delhi High Court bail petition pending since April 2022. The SC directed the HC to act expeditiously. Clearly however, the matters have still stagnated.

- Gulfisha Fatima similarly approached the Supreme Court under Article 32 in Nov 2024 to expedite her HC bail plea; the SC politely declined interim relief but instructed the HC to decide swiftly. Here again, the matter languishes while Gulsfisha remains in jail.

- In May 2023, the SC dismissed the state’s appeal against bail granted to Kalita, Narwal, and Tanha, declaring that other accused could seek bail on parity grounds.

Several petitions request speedy trial direction or time-bound adherence to statutory limits. Yet to date, no constitutional court has set firm timelines, and the trial remains in procedural deep freeze.

Bail under UAPA: the framework

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, by design, constructs a space where bail is not the rule but the exception. This inversion of the ‘bail, not jail’ standard presumption in criminal law is orchestrated through Section 43D(5). The provision stipulates that:

“…no person accused of an offence punishable under Chapters IV and VI of this Act shall be released on bail if the Court, on perusal of the case diary or the report made under Section 173 of the CrPC, is of the opinion that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accusation is prima facie true.”

In practice, this replaces judicial discretion with a form of prosecutorial veto. It empowers the State to, effectively, keep an accused in jail until the court is prepared to rule (not on their innocence, but) on whether the State’s accusations might be believable on their face.

This presumption becomes crucial in cases such as FIR 59/2020, where the “offence” is not an overt act but a constructed chain of intent, coordination, and alleged incitement, which is, in essence, an interpretive and inferential exercise. UAPA thus raises the evidentiary burden at the bail stage and lowers the threshold for incarceration.

Key Supreme Court decisions: The shifting ground

The Watali judgment remains the doctrinal cornerstone for bail under UAPA. The Court held that:

- At the bail stage, courts must not engage in a “detailed analysis of evidence.”

- If the materials prima facie support the allegations, bail should be refused.

This judgment placed extraordinary weight on the accusatory narrative of the police and practically barred trial courts from engaging in critical evaluation of the evidence. Bail became contingent not on the likelihood of conviction, but on the superficial cogency of the State’s documents.

In the years since Watali, multiple High Courts have invoked its ratio to deny bail in UAPA cases involving students, journalists, and civil society members. It became a script, prosecution affidavits were rarely interrogated; the court would peruse the material and affirm its prima facie acceptability.

This case marked a modest pushback. The Court granted bail despite the UAPA bar, on the grounds that the accused had spent five years in custody without trial commencing. The court held that the five and half years Najeeb spent as an undertrial prisoner became a crucial factor. The Court invoked Shaheen Welfare Association v Union of India to hold that ‘gross delay’ in trial violates the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21. A fundamental right violation could be used as a ground for granting bail. Even if the case is under stringent criminal legislation including anti-terror laws, prolonged delay in a trial necessitates granting of bail. Citizens for Justice and Peace has undertaken a comparative analysis of both judgements that may be read here

However, the judgement remains sparse and highly case-specific. In FIR 59/2020, for example, most High Court benches have not invoked Najeeb, despite similar facts.

- Anand Teltumbde v. National Investigation Agency: The Bombay High Court, on November 18, 2022, granted bail to Prof. Anand Teltumbde, accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, making it the first judgement, among 16 accused, to be granted on merits. The bench comprising Justices AS Gadkari and Milind Jadhav held that no prima facie case was made out against Teltumbde to establish that he was involved in any terrorist acts. Charges had been invoked against him under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The court held that offences under section 13 (unlawful activities), 16 (terrorist act) and 18 (conspiracy) of the UAPA are not made out against him. The 72-year-old scholar had been in custody since April 14, 2020 when he was arrested by the NIA. While the NIA challenged this in appeal, the Supreme Court of India upheld the bail given by the Bombay High Court.

4.Vernon Gonsalves & Arun Ferreira v. State of Maharashtra (2023)

In legal and academic circles, Vernon Gonsalves is seen as a vital course correction. The Supreme Court granted bail to two accused in the Bhima Koregaon case and subtly recalibrated the UAPA bail standard set in Watali. While not explicitly overruling Watali, the Court held that a “surface-level analysis of the probative value of evidence” is essential when assessing whether the case is prima facie true under Section 43D (5) of UAPA.

This marked a departure from the mechanical, deferential reading of Watali that discouraged scrutiny of prosecution material. By requiring courts to assess some believability in the evidence and not merely its existence, the Vernon ruling offered a doctrinal opening for more meaningful judicial engagement at the bail stage. Yet, because both rulings came from benches of equal strength, the ambiguity remains to persist, leaving lower courts and prosecutors free to selectively rely on either approach unless the Supreme Court resolves the interpretive conflict explicitly.

The Delhi High Court’s continued deferral of bail orders in FIR 59/2020, despite the arguments being complete and the accused having spent 4+ years in custody, suggests that the inertia from Watali remains dominant.

High Court jurisprudence: Delhi’s reluctance and reticence

The Delhi High Court has had multiple opportunities to apply Vernon Gonsalves and Najeeb, especially in the context of FIR 59/2020. But the pattern reveals caution verging on abstention.

In Devangana Kalita v. State (NCT of Delhi) and related cases involving Natasha Narwal and Asif Iqbal Tanha, the court (bench of Justice Anup Jairam Bhambhani and Justice Mridul) in 2021 granted bail on the ground that protest cannot be conflated with terrorism. The judgment examined the contours of what amounts to a “terrorist act” under Section 15 of UAPA and found that the State had overstretched the charge. They also in almost a prophetic manner stated that though at that point of time, the accused had spent a year in custody, the principle of a constitutional court taking into consideration the right to speedy trial as an aspect of the right to life should apply. This was irrespective of the stringent and restrictive bail provisions following the Judgment of the Supreme Court of India in K.A Najeeb. The court held so because, there was no movement whatsoever (in the trial) for a year. Given the volumes of witnesses and documents, further delay was inevitable, making the accused’s right to life through speedy trial otiose (obsolete) if bail was not granted. This prophecy –and the principles enunciated in those judgements—have come true because five years later, the case has not moved forward at all!

These judgments were subsequently challenged by the State in the Supreme Court, which stayed their precedential value, though not the actual bail orders. As a result, other UAPA accused, despite similar charges and material, could not invoke those bail precedents as binding except for seeking to invite the Courts’ attention to factual parity. It is however quite clear after the Judgments in Ranjitsing Brahmajeet Sing Sharma, Vernon Gonsalves, Shoma Kanti Sen and Sudesh Kedia, that the prosecution’s ipse dixit in the chargesheet is just not sufficient to hold that there is a prima facie case be it simpliciter reading of statements, documents produced along with or the report itself for the courts are (i) required to go through all material and (ii) do a surface analysis of the material to see if the charge of terror is even made out. The Judgment in Watali had been read and interpreted by the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi and Supreme Court of India to mean that the allegations in the Final Report and the statements had to be read as they are. That interpretation is completely flawed for the reason that if that were so, where is the need for the Judiciary? In fact Watali itself says, the material should ‘good and sufficient on the face of it’ such a finding would require some analysis of the material on record. Despite these Judgments in Ranjitsing, Shoma, Vernon and Kedia, Umar Khalid’s bail at every stage has simply been rejected only on the basis of the prosecution’s say so with absolutely no application of mind. It is interesting that Justice Mridul has granted bail to Devangana, Natasha and Asif and in the same chargesheet with lesser allegations and lack of even presence has denied bail to Umar Khalid

In the case of Sharjeel Imam, Gulfisha Fatima, and Meeran Haider, the Delhi High Court has heard arguments multiple times since mid-2022 but has withheld orders. The reasoning is neither public nor transparent. At times, it has appeared that judicial reassignment, rather than doctrinal difficulty, is to blame.

Even when Justice Siddharth Mridul’s bench heard and reserved judgment on some of these bail applications, his transfer derailed the outcome. Despite re-hearings, no decisions have been delivered. Judges who completed hearings have either been reassigned or replaced, returning the pleas to procedural limbo.

UAPA, delay and the punishment of process

Perhaps the most profound tension between bail jurisprudence and the structure of UAPA is the conceptual separation between trial delay and the statutory bar on bail. The prosecution consistently argues that the material is complex, the conspiracy vast, and the trial long. Yet, they simultaneously resist bail even when the accused have been in custody for four to five years.

In Siddique Kappan v. State (2022 Supreme Court), the courts reiterated that prolonged incarceration without trial may violate Article 21, and bail cannot be refused merely on the ground that the UAPA bar exists. Still, the use of these cases remains sporadic.

In theory, Section 436A CrPC allows bail for undertrial prisoners who have undergone half of the maximum sentence (in non-capital offences). But UAPA offences often carry life imprisonment as the maximum penalty, making the threshold meaningless in practice.

The absence of time-bound charge framing, combined with the absence of mandatory periodic bail reviews, transforms UAPA into a tool of preventive detention without having to declare it as such.

Some other judgements in which the Supreme Court has, under UAPA, granted bail, may be read here. On April 6, 2024, the court reversed an order of the Bombay High Court refusing to grant academic Shoma Sen bail. Sen had argued that her prolonged detention since 2018 (six years) lacked prima facie evidence under UAPA and had also highlighted her advanced age and health issues. Though the bail conditions were stringent, the apex court, emphasised the necessity of prima facie evidence under Section 43D (5) of UAPA and underscored the importance of constitutional safeguards against prolonged pre-trial detention. Several judgements have been cited by the Supreme Court in support of its reasoning.

The path forward

What emerges from this study is a judiciary that is simultaneously constrained by precedent and unwilling to revise it. Despite Supreme Court signals in Vernon Gonsalves, Najeeb, and Kalita, many courts persist with the Watali-era conservatism.

To break the impasse:

- Trial courts must critically evaluate “prima facie truth.” If the material is tenuous or contradictory, Watali must not apply. A “surface-level assessment” should become a routine part of bail hearings.

- High Courts should expedite decisions in long-pending bail pleas. That some pleas are heard for 70 sessions without an order erodes public confidence in judicial efficacy.

- Legislative reform may be necessary. A statutory amendment mandating bail review after two years in UAPA cases (much like TADA’s sunset clause) should be considered.

- Judicial continuity should be prioritised. If a bench hears a bail application in full, it should be obligated to deliver an order, or the matter must be reassigned immediately with transcripts provided.

The evolution of UAPA bail jurisprudence is not merely a matter of law, it is a record of how fear, caution, and institutional deference have increasingly replaced scrutiny and principle. When a court does not rule for two years on a bail plea already argued in full, it is not the law that is failing, but the infrastructure around it.

In cases like FIR 59/2020, the punishment is the process. With trials yet to start, charges unframed, and pleas unheard, the UAPA becomes a penal sentence administered without conviction.

The law may say prima facie, but the effect is indefinite detention dressed in the robes of legality. A system that is so allergic to finality may well ask whether it is in the business of justice, or of deferral.

Image Courtesy: Burned shops in North East Delhi. Photo: Banswalhemant / Wikimedia Commons

[1] The Citizens Commission of Inquiry commented upon the unbalanced (read biased) non-application of provisions of the Indian penal Code (IPC) against powerful hate offenders on the one hand (these include the notorious Kapil Mishra, Ragini Tiwari and Yati Narsinghanand among others) and failure to prosecute was matched by the unfair and selective application of the dreaded UA(P)A against young protesters, concludes the report. The absence of setting up of an independent Commission of Inquiry has also been commented upon. The report that may be read here was authored by Justice Madan B. Lokur, former Judge of the Supreme Court (chairperson); Justice A.P. Shah, former Chief Justice of the Madras and Delhi High Courts and former Chairman, Law Commission; Justice R.S. Sodhi, former Judge of the Delhi High Court; Justice Anjana Prakash, former Judge of the Patna High Court; and G.K. Pillai, IAS (Retd.), former Home Secretary, Government of India.

[2] The judge had also observed that Khalid’s bail plea had been earlier rejected by the Sessions Court and his appeal against the order was further dismissed by the Delhi High Court as the latter found the case against the accused prima facie true. Notably, Umar Khalid had filed second bail plea with the Sessions Court after he withdrew his bail application from the Supreme Court citing “change in circumstances” to try his “luck” in trial court. Pertinent, before Khalid withdrew his bail petition from the SC, the case had already witnessed 14 adjournments. Earlier, the Session Court had rejected his first bail application on March 24, 2022, following which he moved to the Delhi High Court, which again rejected his appeal on October 18, 2022. As the Sessions Court rejects his latest bail petition on 28 May, Khalid continues to remain in jail for more than three and half years (this period is now close to five years!) even as some of the co-accused in the case have secured bail, including Natasha Narwal, Devangana Kalita, and Asif Iqbal. Khalid’s counsel pointed out this fact and argued that his client should be granted bail on parity, but the court rejected his arguments.

Related:

UAPA: Delhi HC denies bail, Umar Khalid’s Incarceration to Continue

4 years onward, activist Gulfisha Fatima remains behind bars