Basic structure touchstone for anti-conversion laws hindustantimes.com

06, Nov 2025 | Insiyah Vahanvaty , Ashish Bharadwaj

Spread the word:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

The right to believe — or not believe — is not a gift from the State. It is foundational to human dignity

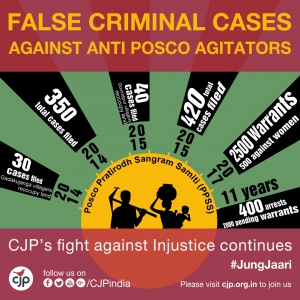

As of August 2024, four years after Uttar Pradesh enacted its anti-conversion law, 1,682 people have been arrested and 835 criminal cases filed under the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion Act, 2021. The number of convictions? Fewer than a dozen. Since then, nine other states have followed suit, including Uttarakhand and Rajasthan, where disproportionately severe amendments prescribe prison terms of up to life.

But India’s uneasy relationship with religious conversion runs deeper. The Constitution guarantees every Indian the right to “freely profess, practise and propagate” religion, yet the State often struggles to distinguish persuasion from coercion. In Stanislaus v. State of MP (1977), the Supreme Court ruled that “propagating” does not include “proselytising”. This narrow reading — although later viewed as a departure from the spirit of Article 25 — nevertheless gave legal cover to the first generation of so-called “Freedom of Religion” laws that claimed to protect choice but often ended up policing it.

Today’s laws go much further. They criminalise conversion through vague terms like force, allurement, or undue influence and reverse the burden of proof. In Uttar Pradesh, anyone intending to convert must inform the district magistrate two months in advance, after which the state will conduct an inquiry to verify if the conversion is “genuine”. Anyone can file a complaint, allowing neighbours, political groups, or vigilantes to trigger investigations.

While these laws claim to protect the vulnerable, their real-world impact is chilling. Vigilantes use them to harass interfaith couples, suppress minority rights, and instill fear in them. Many registered cases involve Muslim men and Hindu women in consensual relationships who now face both social hostility and legal vulnerability. “Love jihad” may have been debunked, but such laws give it legal legs. Claims of guarding against deceitful conversions ring hollow when couples marrying across faiths are arrested, or when volunteers handing out food are accused of enticement. Behind the rhetoric of forced conversions lies a deeper anxiety: Of religious majoritarianism in a nation constitutionally bound to pluralism.

The case now before the Supreme Court, Citizens for Justice and Peace v. State of UP (2020), challenges the constitutional validity of these laws across Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh. The Court must now decide whether these laws violate fundamental rights under Articles 21 (life and personal liberty), 25 (freedom of conscience) and 26 (freedom to manage religious affairs), whether they breach Article 14’s promise of equality, target marriage-linked conversions, or conflict with the Special Marriage Act. The Court has already hinted that these laws may not pass constitutional muster. On October 17, it quashed five FIRs from Fatehpur that alleged mass conversions of Hindus to Christianity, noting they were based on “incredulous material” with no victim complaints, amounting to harassment.

On October 23, in a sharp reminder of India’s secular foundation, it questioned several provisions of Uttar Pradesh’s anti-conversion law, observing that it imposes an “onerous” procedure on those wishing to change faith. Referring to the Preamble and the secular nature of the Constitution, the judges also raised a deeper constitutional concern: whether such laws erode the Constitution’s basic structure.

The concept of basic structure, introduced in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), comprises the set of fundamental principles (such as secularism, democracy, and fundamental rights) that form the core of the Constitution and cannot be altered or destroyed by any amendment or legislation. By reopening this debate, the Court has brought India back to a foundational question: Can a secular democracy dictate the terms of faith? This moment demands a clear-eyed reckoning of societal implications. The fury over Tanishq’s 2020 ad showed us how even a tender image of interfaith love can spark outrage in a climate of fear. By casting such doubts, these laws risk deepening mistrust between communities. Instead of building bridges, they build walls, turning neighbours into watchers and friends into suspects.

The right to believe — or not believe — is not a gift from the State. It is foundational to human dignity. The Supreme Court’s answer will decide whether India’s secularism still beats with its own heart — or survives only by permission of laws.

Insiyah Vahanvaty is a socio-political commentator and author of ‘The Fearless Judge’. Ashish Bharadwaj is professor & dean, BITS Pilani’s Law School in Mumbai. The views expressed are personal

The original piece may be read here

Spread the word:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

cjp in action

Free and Fair Elections: CJP’s 2025 fight against hate and voter intimidation Throughout 2025, CJP challenged electoral misconduct by approaching the Election Commission of India and State Commissions over violation of Model Code of Conduct (MCC), communal vilification, hate speeches and threats of welfare denial, by intervening in documented cases across the country, these complaints sought corrective directions, accountability from public officials, and immediate safeguards to ensure voters could participate without intimidation or inducement

असम में ‘संदिग्ध नागरिक’ से भारतीय नागरिक तक: अनोवारा खातून के लिए CJP की कानूनी जीत नागरिकता सत्यापन के नाम पर गरीब, बांग्ला-भाषी मुस्लिम महिलाओं को निशाना बनाने वाली एक क्रूर व्यवस्था के खिलाफ यह एक जीत है।