3 out of 4 Bohra girls forced to undergo FGM New study makes shocking revelations on the International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM

06, Feb 2018 | Mansi Mehta

A newly published study, titled ‘The Clitoral Hood: A Contested Site’ has found that female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is widely prevalent among India’s Bohra community. The qualitative study, which involved interviews with 94 people–83 women and 11 men–has revealed that 75% of daughters (aged 7 and above) of all respondents had undergone FGM/C, or ‘khafd’, which is typically carried out on girls when they are around the age of seven. 81 of the women interviewed had also undergone ‘khafd’.

The FGM Study can be read here. It was conducted by three independent researchers, in collaboration with WeSpeakOut, a survivor-led movement to end Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting amongst Bohras, and Nari Samata March, a women’s rights group. It included interviews with both supporters and opponents of the practice, with respondents hailing from five Indian states: Gujarat, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. Traditional circumcisers, healthcare professionals and teachers were also interviewed.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is a grim reality for millions of women around the world, with the procedure being carried out despite it lacking any health-related benefits, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). According to UNICEF, at least 200 million women and girls in 30 countries across the world have been subjected to FGM. Every year, more than three million girls worldwide are at risk of being subjected to the procedure. A spokeswoman for the Dawoodi Bohra Women’s Association for Religious Freedom told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that ‘khafd’ and FGM are “entirely different,” and that Bohra culture had “no place for any kind of mutilation”.

However, according to WHO, FGM “comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”

WHO, in a factsheet, outlines four different types of FGM, and its definitions are detailed below:

- Clitoridectomy is the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

- Excision is the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without excision of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

- Infibulation is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy).

- Other procedures on female genitalia that are conducted for non-medical purposes, such as pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterising the genital area.

According to the study, a majority of Bohras practice Type 1 FGM/C, which involves the partial or complete removal of the clitoris and/or the clitoral hood/prepuce.

According to WHO, FGM poses multiple health risks, ranging from short-term risks such as severe pain, excessive bleeding, shock, swelling, and even death due to infections, to long-term risks such as chronic genital and reproductive tract infections, urinary tract infections, menstrual issues, and even HIV. Indeed, 97% of the female respondents in the above mentioned study said they recalled ‘khafd’ as being painful. According to the study, women said that they experienced painful urination, bleeding, and difficulty walking immediately after being subjected to ‘khafd’, and around 33% said they believed that ‘khafd’ had a negative effect on their sex life. Women reported experiencing low sex drive and the inability to feel sexual pleasure, and oversensitivity in the clitoral area. Many respondents also reported experiencing emotions such as anxiety, shame, and depression as a result of having undergone FGM/C.

WHO has said that FGM is practiced most commonly in eastern, northeastern, and western Africa, in some countries in Asia and the Middle East, as well as among communities of migrants from these countries. Recently, a Kenyan doctor, Dr. Tatu Kamau, faced criticism from activists after she filed a petition alleging that Kenya’s ban on FGM infringes on women’s rights to “perform their respective cultures,” according to Kenyan portal Citizen Digital. Kamau has said “female circumcision” is a part of Kenya’s “national heritage”. According to the Guardian, Kamau told a Kenyan television channel that “If women can decide to drink, to smoke, women can join the army, women can do all sorts of things that might bring them harm or injury … a woman can [also] make that decision,” referring to FGM. Kamau said once a woman has decided to undergo the practice, “she should be able to access the best medical care to have it done.”

It is true that FGM is performed because of a number of potential cultural factors. According to WHO, FGM is often deemed “a necessary part of raising a girl, and a way to prepare her for adulthood and marriage.” Another factor is its role in ensuring virginity prior to marriage and fidelity after marriage, especially because many believe it lowers women’s libidos and so helps them resist sexual activity outside of marriage. FGM is also linked to the ideals of femininity and modesty, “which include the notion that girls are clean and beautiful after removal of body parts that are considered unclean, unfeminine or male,” WHO says. In most cases where FGM is performed, “it is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation.” Even the study on the Bohra community found that the practicing FGM include the decision “to continue with an old traditional practice,” and “to control women’s sexual behavior and promiscuity,” among others.

FGM has been declared unequivocally as a human rights violation, and embodies the “deep-rooted inequality between the sexes and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women.” The Thomson Reuters Foundation reported that Sierra Leone has banned the practice during its elections, until March 31, to ensure that candidates don’t attempt to purchase votes by paying for the procedure. United Nations data indicates that nine of ten girls in the African country undergo the practice, making Sierra Leone home to one of the highest rates of FGM in the continent. The practice is part of being initiated into secret societies that are headed by women and possess considerable political power, according to the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Recently, Liberia also banned FGM for one year after outgoing president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf signed an executive order.

On this February 6, the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, it is vital to understand the reasons behind and ramifications of this disturbing practice. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of UN Women has called FGM “an act that cuts away equality” in her statement to mark the occasion. “FGM is a practice passed on from generation to generation, in some countries so commonplace that to be uncut is abnormal: For example in Somalia 98 per cent of women aged 15 to 49 have undergone FGM, in Guinea 97 per cent and in Djibouti 93 per cent,” Mlambo-Ngcuka has said, emphasising, however, that “It can also be stopped in one generation, with the decision as a parent, as a community, as a country, to leave a girl as whole and perfect as she was born.”

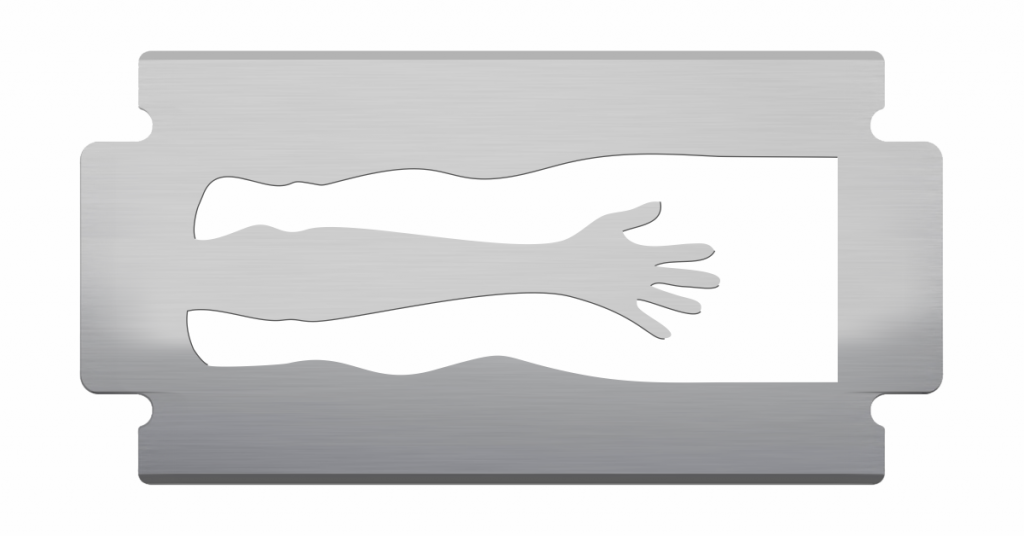

Feature Image illustration by Amir Rizvi

Related resources:

World Health Organization factsheet on Female Genital Mutilation

World Health Organization factsheet on health risks posed by FGM