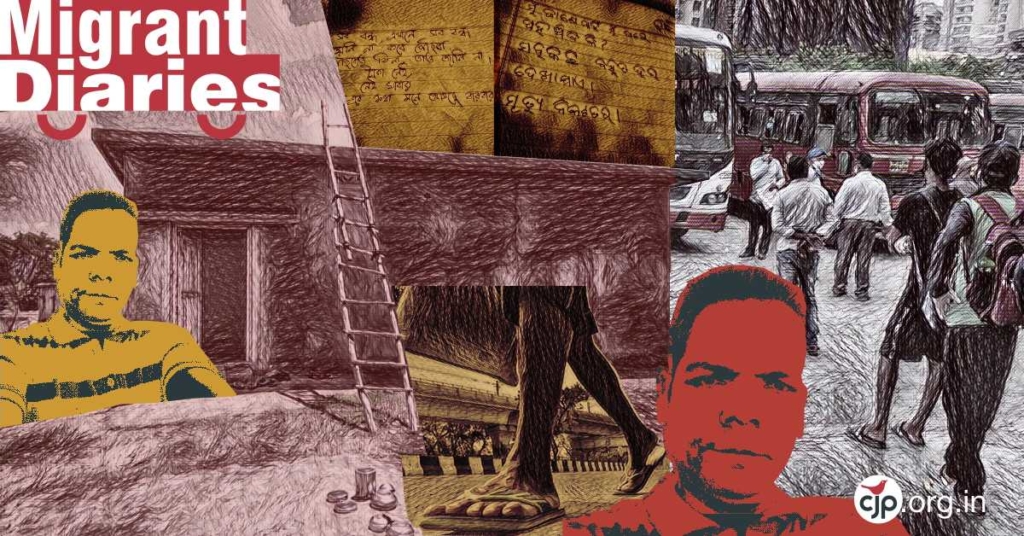

Migrant Diaries: Hrudanand Behera "I am haunted by the images of the thousands I saw walking home to escape the big city," says a migrant worker from Odisha still bleeding from the emotional scars of a forced exodus

10, Jun 2020 | CJP Team

“I used to work for four months in Mumbai and then go back home to my village Biripali, which is in Bolangir district of Odisha, for 15 days. I would take care of whatever needed to be done at home, attend to the needs of my parents, wife, and daughters, and then get back to Mumbai to resume work for the next four months,” Hrudanand Behera, a skilled repairman, had his calendar down pat. He has not really strayed from it in the 20 years that he has lived and worked in Mumbai. This routine has helped him earn reasonably well and he enjoys his work at Painteria so much that he has never thought of a job change.

Behera’s colleagues, many of whom hail from the same district, are his Mumbai family, and together they have worked hard for the painting and repairing company which has done well in the South Mumbai area. “I am in the repairing department, basically we do waterproofing, sealing and repairing. My monthly salary is Rs. 20,000,” he says he would send Rs. 15,000 back home and manage with the Rs. 5,000 that remained, he lived a simple life.

After the lockdown, many migrant labourers were forced to choose between two extremely difficult options; continue to stay in expensive cities where expenses kept mounting and income sources dried up, or go back home to their families in their villages, but face an uncertain economic future. While CJP has supplied rations and essentials to thousands of migrant labourers who both stayed on and some of those who left, our challenge is now, in a post lockdown solution, help find short and long term solutions, with them. Our series Migrant Diaries brings to you stories of the ordeals they were forced to face as they took an arduous journey back home, and some stories of those who stayed back. Please donate now to help our migrant brothers and sisters. CJP hopes to evolve collective solutions and programmes with them, in the coming weeks.

However, everything went awry as soon as the national lockdown was suddenly announced when Covid-19 cases began to rise. “Our work stopped completely, and we were soon struggling for food,” he recalls. The situation was spiraling towards doom at breakneck speed and Behera did not know what to do. “At one point during the lockdown, things were so bad that my wife had to send me Rs. 5,000,” he says full of anguish. This shook him up, as it was he, who had always sent money home, and now his wife had to dip into the savings and send him money, so he could survive. “The situation was really getting tough for us, and the police did not allow us to even step out. Staying locked in a small space was the worst feeling,” he remembers the discomfort even though many days have passed since he left the city.

Behera and his group of 22 others were under great stress when the volunteers of Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) met them. The team had helped over 6,000 migrant workers after the lockdown, and each one had a story to share. The CJP volunteers coordinated the relief work with the District Collector of Mumbai city and arranged for ration supplies to be provided to Behera’s group.

The men had also expressed a wish to return home and asked the CJP team to assist them in filing the emergency travel forms that were needed to get enlisted for the Shramik Special trains departing from Mumbai. He and his friends have reached their village Biripali and are now under home quarantine.

When the CJP volunteers called him to ask how he was feeling, Behera had plenty to share. Things were not easy even though he was back home with his family now. While earning enough money has always been a struggle this is perhaps the worst phase for the family. Behera says he has never dealt with such a situation in his life. “The loss of two months of salary will be difficult to cover up, and now no one knows when will this get over,” he said over the phone.

At home, he remembers that it was the civil society members who came to help us, “You know the CJP ration kit lasted for a month.” After that he and his group also had to request more ration, “Even though our families sent money it was impossible to go out to buy ration. Somehow we survived the two months but slowly started losing our patience. Then we heard of the news that trains were going to start and it gave us so much relief. My group and I filled the emergency travel form and submitted it at the Prabhadevi police station,” he remembers feeling frustrated as there was no response from the administration, “We didn’t receive any call for 10 days, and were hearing that the trains were also getting cancelled every day.”

So, they had no option but to wait till they came to know that one Sarika Jain, an IAS officer who hailed from Odisha could help. “We heard the officer and an NGO volunteer Pankaj Aggarwal were arranging buses for migrants from Odisha to go back to their villages. We were told these buses had all the government permissions needed. Finally, we got a call from some officials that the buses were ready and they asked us to pack our bags,” he recalls. The group elected a leader who was added to a WhatsApp group and everything was coordinated with them.

“Then on the evening of May 15, we boarded a bus from Mumbai Central. There were 30 people in the bus, and while boarding we were given masks, snacks, fruits, water bottles, and our journey started. I was so happy to finally go back home,” he says that he was pleasantly surprised that the entire process was smooth and hassle free.

But he soon realised he was among the lucky ones. En route he saw something that still haunts him. “I sat near the window, and soon could see many migrants walking, and struggling to reach their home, I was feeling bad for them,” he remembers. He was reassured that there were volunteers offering food, fruit, snacks, water, juices to the migrants but did not accept anything himself. “My group and I didn’t take anything. We were scared of Coronavirus. We had lunch and dinner at dhabas along the route and paid for it ourselves,” he says.

On May 17 afternoon at about 1 PM, the bus reached Karia Road which is on the Chhattisgarh and Odisha border. “There we had a health screening and they recorded details like our Aadhaar Number, Mobile Number, and village’s name. Then, we all were taken to our respective villages by Orissa government buses,” he added that he and some others got off at Biripali, and were sent to quarantine for the next fortnight. “On June 1 ,we were told to go home and be under home quarantine. We were told not to go out unless there was an emergency. We requested the doctors to test for Covid-19 but were told we had no symptoms, they were only testing people who showed some symptoms,” he recalls.

Behera says he is happy that he has reached home safely but is aware that the financial struggle will begin afresh. “We are going to face a lot of difficulty due to unemployment and ultimately we will have financial issues. But I am with my family now which is most important to me. I am thankful to all the people who helped us during this crisis. I hope that things get back on track, and the state government provides us with some opportunity for work, so that we can at least earn for our daily living,” says Behera.

His optimism, backed by his will to work hard, will help him brave this storm too. Hopefully, the government of Odisha is looking out for the workers who have always sent money, money that was also added by their families’ spending, right into the state’s coffers.

Related:

CJP comes to the rescue of migrant workers facing starvation amidst the lockdown!

COVID-19 Crisis: CJP’s commitment to Mumbai’s migrant workers