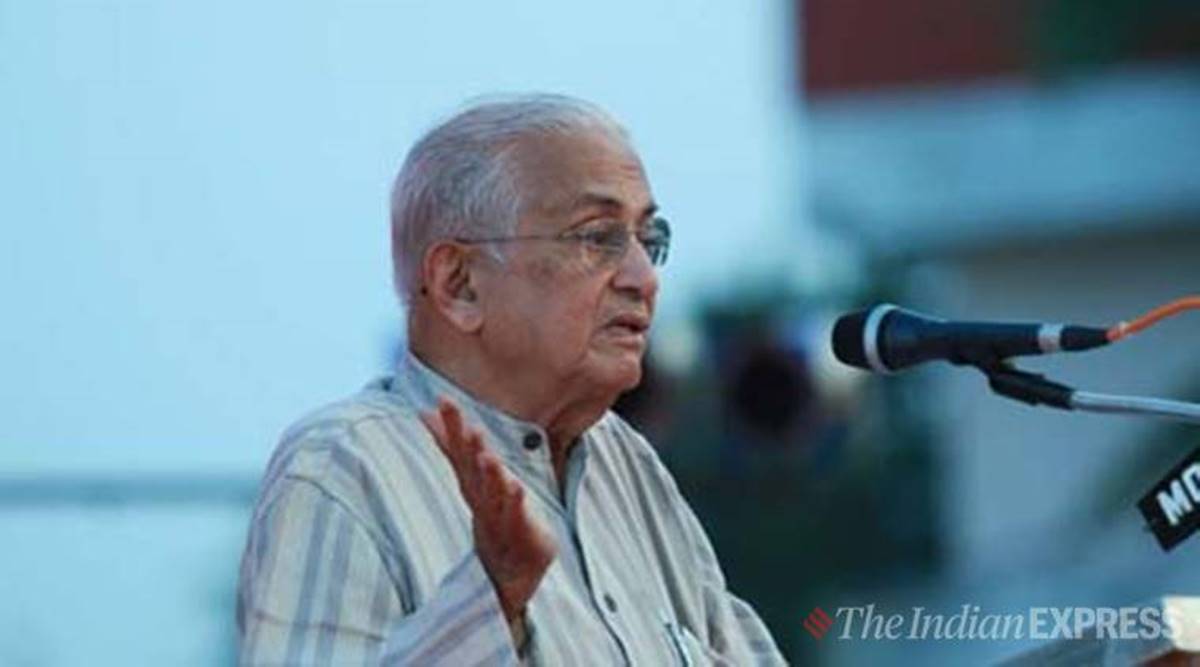

Justice Hosbet Suresh: His voice, his conscience Indian Express

19, Jun 2020 | Teesta Setalvad

All his life, Justice Suresh believed and practiced tenets of equity and fairness.

Will Justice Hosbet Suresh, who passed away on June 11, be remembered as one in whose mind the constitutional pledge to every Indian was uppermost? Will he be remembered for the trendsetting jurisprudence set in the Sharad Rao v/s Subhash Desai judgement — in an election petition that unseated an MLA for corrosive electioneering? Will he be remembered because with men (and women) like him on the bench, the lawyer and citizen felt “safe”? Because, whatever the outcome of a particular case, justice would be done and the constitutional mandate upheld?

Much has been written on the qualities of a judge: A sense of fairness, an unflinching commitment to delivery of justice, integrity, an astute grasp of not just the formal sections of the law, but its intent, compassion and courage.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Justice Suresh had the near-perfect judicial temperament. Or that the understanding Justice Suresh (and many before and after him) held, of what is the real function of the judiciary and the judge is more an exception than the rule today: To be the ultimate arbiter (and guarantor) of both — equality of life and equality before the law.

A significant judgement delivered by him was as a judge of the city civil and sessions court, Bombay. He interpreted (40 years ago) Hindu law to allow the son of a prominent family born out of marriage to be recognised as a legal entity, and thereby, be entitled to some share in the ancestral property. As a High Court judge, in 1994, he courageously interpreted section 123 (a) and 123(b) of the Representation of People’s Act and struck down the election of an MLA, Subash Desai. He looked hate politics in the eye, and, along with several of his upright and courageous colleagues at the time (Justice VR Krishna Iyer, PB Sawant, KG Kannabiran, Aruna Roy, Ghanshyam Shah, Tanika Sarkar), spoke unflinchingly of the human rights violations in Gujarat in 2002 (Concerned Citizens Tribunal, Crimes Against Humanity, Gujarat 2002).

When the system starts faltering, even failing, and shows deep cracks and schisms, alternatives start to emerge: Justice Suresh not only recognised it, but was deeply affected by this failure. This led him to pioneer, with mentor Justice Krishna Iyer as guide, the people’s inquest, the people’s tribunal. It took him to the farthest reaches of India — villages and conflict zones — where, for him, real and substantive compassionate justice could come only after listening to the voices of the victims of denial and violations, and of the inaccessibility to justice. Which ones should I name here, even as we begin the task of collecting and annotating this vast library of alternate jurisprudence?

The inquiry he headed into the riots following the Cauvery Water Dispute, Bangalore (1991), the “people’s verdict” he delivered with Justice S Daud in the post-Babri Masjid demolition violence in Bombay in 1992-1993, the forced evictions of slum dwellers by the authorities in Bombay in 1994, the inquiry into the harmful effects of prawn farming on the eastern coast that led the Supreme Court of India to thereafter ban prawn farming (1995), the commission he was part of that investigated the merciless drowning of Dalits by the Tamil Nadu police (1999), the brutal shooting down of tribals in Devas, Madhya Pradesh or the commission he headed that looked into police and paramilitary excesses and torture in Manipur in 2000 — this led the Supreme Court, close to two decades later, to order investigations, as a consequence of which, now, such brutality is substantially reduced.

“My voice is my conscience”, he would say to us, clear and firm that a justice sitting on the bench owed it to litigants and citizens alike, to audibly deliver his verdict. For the vast community of human rights defenders and lawyers mentored by him, he was both a passionate shining star that oozed optimism, and a gentle guide and friend. His humility, sense of humour and rigour were unique. He was also the ultimate feminist, believing in equal and joyous spaces for women.

When he began to practice in Bombay, he would devote eight to ten hours a week teaching at the city’s night schools. A commitment to the less privileged that led him to continue to support the school that his family had established in Surathkal, Karnataka. To Rama, his late wife (who the family lost in 1993), to his son, and most of all to Rajini, Malini and Shalini, his three surviving daughters and their families, we can only say, “you shared with us a man who was so special and rare, they just don’t make enough of them like him anymore.” His voice is the conscience of all Indians. Ameen.

The author is secretary, Citizens for Justice and Peace and co-editor Sabrang India

This article originally appeared in the Indian Express and may be read here.