Fate of human rights in India The Tribune

22, Jul 2022 | Shiv Visvanathan

Dormant for too long, civil society must learn to protect its exemplars

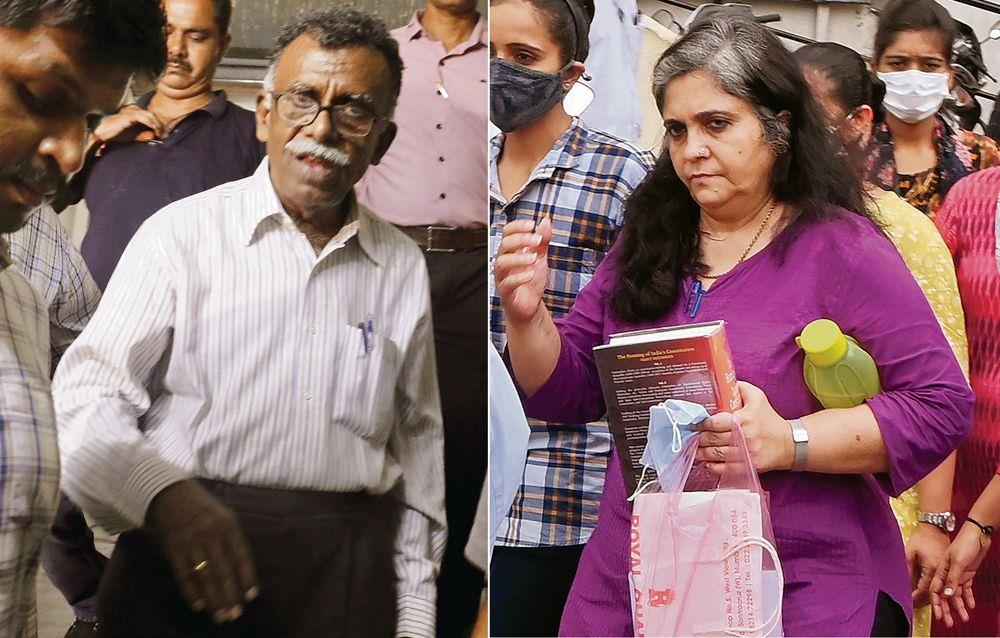

Demonisation: Like the ‘Urban Naxal’, Sreekumar and Teesta are seen as a threat to democracy and the law. PTI

Last fortnight was a sad one for me. My two friends, Teesta Setalvad and ex-DGP Sreekumar, were arrested. The sadness was deepened by the reactions that followed. Teesta and Sreekumar are not mere knee-jerk activists. They have a vision of the world. For Teesta, the Constitution is a playground of new freedoms. For Sreekumar, Sanskrit is a way of looking at the world, where an ethical reality comes alive with each sloka. They are both professional people with a deep sense of dignity in their concern for India.

What do the ordinary citizen and the argumentative Indian do when dissent, instead of being a part of the fabric of culture, is defined as unpatriotic and anti-national?

The silence around the arrests, beyond the protest of the few standard groups, was worrying. They are citizens acting as concerned individuals, struggling for 20 years to find and state the truth of a society. There is little sense of an ego trip as they struggle with the bureaucracy. Like Stan Swamy, Teesta and Sreekumar are activists who have fought for life-giving rights. Yet, the court and State read them as amateur busy-bodies, seeking to forge events and fostering conspiracies. I was wondering why ordinary citizens did not react to the obscenity of the situation. Was it fear, indifference, tiredness?

Is it a sign of things to come? What do the ordinary citizen and the argumentative Indian do when dissent, instead of being a part of the fabric of culture, is defined as unpatriotic and anti-national? Like the ‘Urban Naxal’, Teesta and Sreekumar are seen as a threat to democracy and the law.

She made the above point as an anthropologist. She said the court and the CBI acted as custodians of the textual domain, playing guardian of minutes of the meeting, procedures, records. It displayed a clinical correctness which is not truth. Sanitising documents does not lead to the truth. It is not an assembly line of certifications. One has to battle hard to tell the truth. It is time human rights reclaim the storyteller and recite these stories from Stan Swamy to Sreekumar. Memory, the cultural memory of rights battles, has to become a significant part of such efforts. Memory has a different flavour, even authenticity from record when the State becomes a custodian of the latter. I remember schools would have moral science classes where such anecdotes would be told. We have to return to that pedagogy of rights. One has to capture rights as a pilgrimage, a search for truth beyond State certainties. The nature of the quest is different. In telling the story this way, one is honouring all the Teestas and Sreekumars of the world.

India is moving from majoritarianism to authoritarianism. Its indifference to margins, informal economics, minorities is increasing. Authoritarian socialities and other forms of communication, especially as media, add to the obscenity of the regime. An informal economy of truth was kept alive as memory by the civil society. Our civil society has been dormant for too long, allowing parties to take over, or worse, letting them be the simulacrum of our civil society. I remember Sreekumar would be invited by literary groups in Kerala to tell his story. They would cross-examine afterwards. It is that sense of openness and debate we need to recreate. A civil society must learn to protect its exemplars as living testimonies to a visionary right, not just the details of the case. The human rights records of the Setalvad family from Independence to now are worth looking at as a testimony in its own right. It tells you about the traditions across generations of treating human rights with a different texture of respect.

The second phase he called discourse, the framework of culture, through the concept around which law as thought is built. This needs metaphysics, a study of the ‘tacit Constitutions’, the unstated unconscious around ideas. One has to look at violence, justice and ways of being. Rights have to be located between property and commons. An exegesis of rights as a metaphysic becomes critical.

Finally, there is the paradigm of law, the case as is unfolding. One has to ask what the role of law and lawyers is. How do they react, read the text? Do national law schools greet such a verdict in silence, or is the argumentative India a part of the law? One has to read the Teesta episodes through all three gradients. From a particular case it becomes a lens, a kaleidoscope for reading the fate of rights in India. One hopes between pedagogy and the new civil rights politics, a different stand is taken, and the Stan Swamys, the Sreekumars feel that their vision of life is not lost on the new generation.

The original piece may be read here