Election symbols controversy: violation of democratic principles in Satara, M’tra Analysis of legal implications of ECI's Role in upholding fairness and transparency amidst allegations of voter confusion over similar symbol allocation.

13, Jun 2024 | Hasi Jain

Among the myriad discrepancies and malpractices alleged in the recently conducted polls, mirror or mixed symbols causing defeat and close victories in Maharashtra is one of them!

The debacle of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-Shiv Sena (Eknath Shinde)-Nationalist Congress Party (NCP-Ajit Pawar) combine (MahaYuti) in the western Indian state of Maharashtra was despite and in spite every effort to trick the voter into confusion.

Never has been the voter’s faith in the electoral process been at such an all-time low. The questionable conduct of the Election Commission of India (ECI) in a) failure to act against the brazen incitement and use of religion during the campaign by star campaigners like the Prime Minister and others from the ruling BJP; b) the ECI’s hostile and unaccountable behaviour in not releasing the figures of the Form-17C (that gives the total of votes polled from every constituency within 48 hours of the poll) and c) general hostile attitude towards the opposition and civil society increased scepticism and anger.

Before the onset of the poll process in March 2024, the obviously partisan behaviour of the ECI in awarding original party status to the breakway Shiv Sena and NCP rather than the original generated further resentment. Finally, during the recent electoral debacle in Maharashtra’s Lok Sabha constituency significant concerns regarding the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) allocation of election symbols have also come to light.

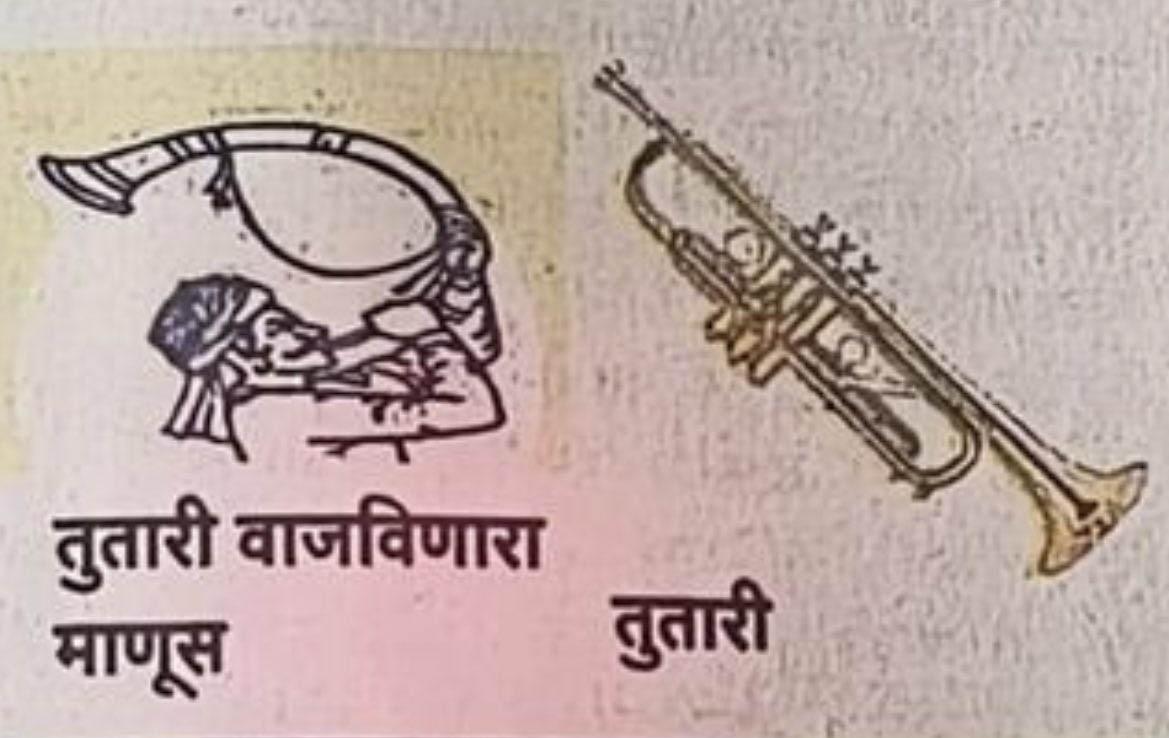

In the Maharashtra’s 2024 elections, splits within major political parties like the Shiv Sena and the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) created significant voter confusion due to changes in party symbols. While the SS (UBT) was tasked with conveying to its loyal voter base that the bow and arrow needed to be overlooked for the new symbol of torchlight (Mashaal), NCP (SP) had to ensure that their voter base did not go for the Clock (Ghadiyal) but pressed the EVM button on the Tutari (man with the trumpet. However, after polling day came and went and counting day ensured that NCP(SS) romped home with 8 of the 10 seats in the Maharashtra Vikas Aghadi Alliance (MVA), the near certain Satara seat was lost because of another smbol of just a trumpet was also awarded to a rival candidate.

This phenomenon was particularly evident in four critical constituencies: Satara, Dindori, Shirur, and Baramati, where voters struggled to identify their preferred candidates’ symbols. This confusion impacted voting outcomes and highlighted deeper issues within the state’s political landscape.

Was the ECI actions in awarding visually similar or interchangeable symbols right in the eyes of law and the Constitution or juridically questionable violating the basic principles of free and fair elections in a democracy?

What conspired in Satara?

In Satara the similar symbol confusion cost the NCP (SP) one Parliamentary seat. In the 2024 Lok Sabha elections for the Satara constituency, the NCP (Sharadchandra Pawar faction) fielded Shashikant Jayvantrao Shinde, whose symbol was a man blowing a tutari (trumpet). Meanwhile, an independent candidate, Gade Sanjay Kondiba, was allotted a tutari (trumpet) symbol. The similarity between the symbols allegedly caused confusion among voters, contributing to the defeat of Shinde by a margin of 32,771 votes to BJP’s Udayanraje Bhonsle. Patil claimed that the allocation of similar symbols was a deliberate attempt to split votes, which is a serious allegation that warrants a thorough legal examination. The confusion over similar symbols could well have cost the NCP (SP) one seat.

D confusing symbol in election plays spoilsport role. Sharad Pawar’s NCP (SP) nominee Shashikant Shinde lost LS polls due to this only. Shinde lost by 33,000 votes while proxy symbol having independent nominee got 37,000 vote. In other seats, proxy symbol reduced victory margin. pic.twitter.com/1t2Dd7FUHH

— Sudhir Suryawanshi (@ss_suryawanshi) June 7, 2024

What conspired in Dindori?

In Dindori, the confusion over symbols was also palpable. In the Dindori constituency, an independent candidate named Babu Sadu Bhagre, who had a similar name and symbol to Bhaskar Bhagre from the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), caused a significant stir. Bhaskar Bhagre was running against the sitting MP, Bharti Pawar from the BJP.

Babu Bhagre, although largely unknown and not a teacher (despite using “sir” in his name), started getting a lot of votes from the beginning. His symbol was a ‘Tutari’ (trumpet), which looked very similar to the NCP’s symbol, confusing voters.

After four rounds of vote counting, Bhaskar Bhagre was leading by 6,989 votes, but Babu Bhagre had already collected 12,389 votes. By the end of the counting, Babu Bhagre had over 103,632 votes. Despite this, Bhaskar Bhagre managed to win with 577,339 votes, beating Bharti Pawar by 113,119 votes.

Narhari Zirwal’s support for Bhaskar Bhagre, despite recently crossing over to Ajit Pawar’s faction, added another layer of complexity. Voters found it difficult to keep track of the political realignments and symbol changes, leading to potential mis-votes. This situation in Dindori exemplified the broader state-wide confusion, where voters’ long-standing associations with specific symbols were disrupted, necessitating intensive educational campaigns that were not always successful.

What conspired in Shirur?

In Shirur, the electoral confusion was similarly pronounced. Amol Kolhe from the NCP (Sharad Pawar) was pitted against Adhalrao Patil from Ajit Pawar’s NCP. Reports indicated that senior voters accidentally voted for the clock symbol, traditionally associated with Sharad Pawar, but now representing Ajit Pawar’s faction. This error stemmed from muscle memory and deeply ingrained voting habits.

Despite Sharad Pawar’s faction’s efforts to educate voters about the new tutari symbol, many still inadvertently supported the rival faction. Campaigns involved using placards and real tutaris to familiarize voters with the new symbol, but these measures were not entirely effective. The voters’ confusion in Shirur underscores the challenges of shifting symbol recognition and the significant impact on voter behavior and election outcomes. Fortunately the outcome was not affected, and Dr. Amol Ramsing Kolhe of the Nationalist Congress Party – Sharadchandra Pawar won with 6,98,692 votes, second came Adhalrao Shivaji Dattatrey of the Nationalist Congress Party with 5,57,741 votes and the independent candidate with the tutari symbol Manohar Mahadu Wadekar came third with 28,330 votes.

I voted. But observed a disturbing trend.

The problem is that the BJ Party has muddied the waters in MH by design. I belong to the Shirur constituency where Amol Kolhe (NCP-Sharadchandra Pawar, with INDIA bloc) was against Adhalrao Patil (NCP-Ajit Pawar, with NDA).

1/n— Kedar Anil Gadgil (@KedarAnilGadgil) May 13, 2024

What conspired in Baramati?

Baramati saw the peak of symbol confusion, with Supriya Sule from Sharad Pawar’s NCP competing against her sister-in-law Sunetra Pawar from Ajit Pawar’s faction. The outcome was however not affected. Supriya Sule of the Nationalist Congress Party – Sharadchandra Pawar won with 7,32,312 votes, second came Sunetra Ajit Pawar of the Nationalist Congress Party with 5,73,979 votes and third came the independent candidate with the tutari symbol Mahesh Sitaram Bhagwat who gathered 15,663 votes.

The situation was further complicated by the presence of an independent candidate who was allotted a symbol similar to the tutari, leading to additional voter confusion.

Despite extensive campaigning by Supriya Sule’s team to make voters aware of the new tutari symbol, traditional voters who had long associated the clock symbol with the NCP accidentally voted for Ajit Pawar’s faction. This confusion split the vote and demonstrated the deep-rooted challenges of re-establishing party identity amidst changing political symbols. The voter misalignment in Baramati highlighted the broader issue of symbol recognition in the face of political realignments.

Legal Violations and procedural failures in the allocation of election symbols by the ECI

The Election Commission of India’s (ECI) allocation of a man blowing a tutari to the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) candidate and a tutari to an independent candidate in the Satara constituency, changing the symbol from the clock to the tutari and allotting the clock to other candidates in Baramati and Shirur constitutes a violation of Paragraph 4 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968.

This provision requires the allocation of “distinct symbols to different candidates in the same constituency to prevent voter confusion,” which clearly occurred in Satara and Dindori as voters likely mistook the independent candidate’s tutari symbol for the NCP candidate’s symbol, leading to a misallocation of votes.

Moreover, paragraph 4 requires that symbols allotted to a recognized party should be frozen and preserved during a split until the Election Commission or a court resolves the matter. In Shirur and Baramati, the emergence of a new symbol without clear guidance on symbol preservation for the different factions within the NCP may have contributed to voter confusion. This confusion was exacerbated in Baramati by the presence of an independent candidate using a symbol similar to the tutari, further complicating the electoral landscape and potentially violating the spirit of symbol reservation and allotment rules.

Furthermore, this allocation reflects a misclassification under Paragraphs 5 and 6, which distinguish between “reserved” and “free” symbols. Reserved symbols are meant to preserve the unique identity of recognized political parties in the electoral process. By permitting an independent candidate to use a symbol so similar to that of a recognized party, the ECI blurred this critical distinction, diluting the party’s identity and confusing the electorate, thereby undermining the intended purpose of these provisions.

Article 324 of the Indian Constitution vests the ECI with the responsibility to ensure free and fair elections. The alleged deliberate allocation of similar symbols to cause voter confusion stands in stark contrast to the mandate of Article 324. The ECI’s primary role is to maintain the integrity of the electoral process, and actions that compromise this integrity violate the spirit of this constitutional provision.

Section 123(2) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 defines corrupt practices, including undue influence. The allocation of similar symbols can be perceived as a tactic to confuse voters, constituting undue influence. The significant number of votes that went to the independent candidate with the similar symbol in various constituencies, as cited by NCP leader Jayant Patil, suggests that voters were misled. This misdirection of votes not only affects the fairness of the election but also undermines the democratic process.

This act also contravenes the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961, specifically Rules 5 and 10, which empower the ECI to specify, reserve, and allot election symbols. These rules are intended to ensure clarity and fairness in the symbol allocation process, preventing voter confusion and guaranteeing that each candidate is distinctly represented by their symbol. By disregarding these rules and allowing symbols that are strikingly similar, the ECI undermined the fundamental purpose of these provisions, leading to a compromised electoral process where voters were misled, thus failing to uphold the principles of fair and transparent elections.

The election symbols, did the exact opposite of what they were supposed to do: they created more confusion, which led to people voting for the opposite party.

Free and Fair Elections: The cornerstone of democracy

Free and fair elections are the bedrock of any democratic system. They ensure that the will of the people is accurately reflected in the composition of the government. The sanctity of elections is protected by laws and regulations that seek to prevent any undue influence or manipulation. The Supreme Court of India, in the case of People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) vs. Union of India, reinforced this principle by holding that democracy is a part of the basic structure of our Constitution and that free and fair elections are integral to this structure. The court emphasized that any action undermining the fairness of elections would be detrimental to the democratic framework of the country.

The Model Code of Conduct (MCC) is a set of guidelines issued by the ECI to regulate political parties and candidates prior to elections. It aims to ensure that elections are conducted in a free and fair manner and that no party or candidate gains an unfair advantage. However, the conduct of ECI in the Maharastra constituencies suggest a blatant violation of the MCC by the commission itself. By allowing similar symbols and confusing symbols to be allocated, the ECI has failed to uphold the principles of the MCC, which it is mandated to enforce.

In Union of India vs. Association for Democratic Reforms, the Supreme Court reiterated that the rule of law and the right to free and fair elections are basic features of democracy. The court stressed that electoral malpractices and undue influence over voters must be prevented to preserve the integrity of the electoral process. The actions of the ECI in the Satara case seem to contradict this judicial mandate by creating a scenario where voter confusion was inevitable.

The Broader Implications

The integrity of the electoral process hinges on the trust of the electorate. When voters are presented with symbols that are similar or are confusing, their confidence in the system’s fairness is undermined.

The confusion caused by the allocation of a “man blowing a tutari” symbol to the NCP candidate and a “tutari” symbol to an independent candidate in Satara likely led to voters being unable to accurately distinguish between the candidates. This not only happened in Satara but four other constituencies. This misallocation of votes can result in feelings of disenfranchisement and suspicion towards the electoral authorities, thereby eroding trust. When voters perceive the electoral process as flawed or manipulated, their willingness to participate in future elections diminishes, which is detrimental to the functioning of a healthy democracy. Ensuring that every vote accurately reflects the voter’s intent is crucial for maintaining public trust and upholding the legitimacy of elected officials.

The implications of the ECI’s actions extend beyond this single instance. If the issue of (deliberately allocated) similar symbols is not addressed, and that too soon, it establishes a dangerous precedent that could be exploited in future elections.

Other political entities may adopt similar strategies, deliberately selecting symbols that closely resemble those of their opponents to confuse voters and split votes. This tactic could become a pervasive form of electoral manipulation, complicating the voting process and increasing the incidence of contested elections. Such practices not only disrupt the immediate electoral outcomes but also contribute to a longer-term degradation of electoral integrity. Over time, if such practices are not curbed, the overall credibility of the electoral system may be compromised, leading to widespread disillusionment and disengagement among voters.

The Maharashtra cases underscores a critical need for more precise regulations regarding the allocation of election symbols. The ECI must take proactive steps to ensure that symbols assigned to candidates are distinct and easily distinguishable to prevent any confusion among voters. This could involve revising the criteria for symbol allocation and implementing stricter guidelines to avoid any overlap or similarity between symbols. Furthermore, enhanced scrutiny during the symbol allocation process could help identify and rectify potential issues before they impact the election.

Clearer regulations would also empower candidates and political parties to raise objections more effectively when they believe that the assigned symbols are likely to cause confusion. By setting and enforcing stringent guidelines, the ECI can safeguard the electoral process, ensuring that voters can make informed decisions without ambiguity. This approach would help maintain the clarity and transparency essential for free and fair elections, reinforcing the democratic principles on which the electoral system is based.

Conclusion: Upholding democratic integrity

To uphold democratic integrity, it is imperative for the ECI to implement stricter regulations and more robust guidelines regarding the allocation of election symbols. Symbols must be distinct and easily distinguishable to prevent any possibility of voter confusion. Additionally, the ECI must engage in proactive voter education campaigns, especially when there are significant changes in party symbols due to political realignments. Voters need to be clearly informed about these changes to ensure that they can make informed decisions at the ballot box.

Ensuring the clarity and transparency of the electoral process is essential for maintaining public trust in democracy. The voters’ confidence that their votes will be correctly attributed to their chosen candidates is fundamental to the legitimacy of elected officials and the overall functioning of a democratic system. By addressing the issues highlighted in Maharashtra’s 2024 elections, the ECI can reinforce this trust and safeguard the democratic framework of the country.

In conclusion, the ECI needs to immediately take decisive action to rectify the symbol allocation process and prevent future electoral confusion. Upholding the principles of free and fair elections is not just a constitutional mandate but a moral imperative to preserve the integrity of India’s democracy. By ensuring that every vote is accurately counted and reflects the true intent of the voter, the ECI can uphold the sanctity of the electoral process and maintain the foundation of a robust democratic society.

[1] https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/similar-poll-symbols-led-to-skewed-results-ncp sp/article68260814.ece

[2] Maharashtra: Similar poll symbols led to defeat in Satara, says NCP(SP) (scroll.in)

[3] https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pune/maharashtra-dindori-unknown-candidate-garnered-99000-votes-9371782/

[4] https://scroll.in/article/1068006/bow-and-arrow-or-torch-in-maharashtra-confusion-over-new-election-symbols-may-help-bjp-allies

[5] https://scroll.in/article/1068006/bow-and-arrow-or-torch-in-maharashtra-confusion-over-new-election-symbols-may-help-bjp-allies

[6]https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_3_81_00001_195143_1517807327542&type=order&filename=Election%20Symbol%20Order,%201968.pdf

[7] https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2096/5/a1951-43.pdf

[8] https://old.eci.gov.in/files/file/15145-the-conduct-of-elections-rules-1961/

[9] People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) vs. Union of India, (2003) 2 S.C.R. 1136

[10] Union of India vs. Association for Democratic Reforms (2002) 5 SCC 294

Related :

Why Indian exit polls are often biased and favour the ruling party