Media under Modi Challenges before free press in the world’s so called largest democracy

06, Mar 2018 | Gurpreet Singh

I am here to make a case that India, which is known as the world’s so-called largest democracy is currently going through an era of self-imposed media censorship under a right wing Hindu nationalist Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) government. This has not only made the working environment of journalists in India extremely challenging, but the problem has spilled over to places like Canada, impacting the South Asian media outlets even in Greater Vancouver.

The journalists working both, in India and for South Asian media outlets here, are finding it difficult to take a critical look at the policies of the Indian state and freely express opinions which are not favourable to the government. The stories that are not to the liking of people in power, often result in intimidation, threats, legal action and loss of employment.

According to the 2017 World Press Freedom Index by global media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, journalists in India are less free than 135 other countries due to threats, particularly from the “Hindu nationalists”, owing allegiance to the ruling BJP. India has been ranked at 136th place out of 180 countries. A year ago, it was ranked at 133rd position. The report claimed that the journalists in India were increasingly becoming the targets of online smear campaigns by the Hindu radicals.

Prosecutions are also used to gag journalists who are critical of the government, with some prosecutors invoking Section 124a of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), under which ‘sedition’ is punishable by life imprisonment. The IPC is a legacy of the British Empire. Section 124 a was often used by the British against freedom fighters. A campaign is already going on in India for abolition of this law. This section has encouraged self-censorship in the media sector.

The ‘India Freedom Report: Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression in 2017’ by The Hoot, presented a more horrific picture of the media landscape in India. According to the report, the year 2017 saw 11 journalists murdered. Among them was Gauri Lankesh, the editor of the weekly Lankesh Patrike, shot dead at her residence in Bengaluru in September. Lankesh was highly critical of the growing attacks on religious minorities in India under BJP rule. The BJP supporters justified her murder on social media. So far, no headway has been made in her case, even as investigators see a pattern behind her murder and the previous assassinations of critics of the Hindu Right.

This is not to suggest that the previous governments were more open and liberal. In fact, India has a history of press censorship. Back in 1975, then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the leader of the centrist Congress party had imposed a state of emergency all over the country. Until the emergency was revoked in 1977, censorship was imposed on the press and the government cracked down heavily on the opposition parties, including the BJP and the civil rights activists. Thousands of people were jailed. Gandhi did that after the courts declared her election to the parliament null and void, and unseated her after finding her guilty of election fraud. Citing security reasons, the government declared the emergency.

Ironically, the current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is the leader of the BJP, went underground during that period to evade arrest. Modi disguised himself as a Sikh during this period. He is the same guy whose government is bashing the Sikhs in Canada accusing them of spreading extremism and violence. Though the Indian masses punished Gandhi in the next general election, after the emergency was lifted and fresh polls were held, a precedent for stifling press freedom was set.

The current situation in India is often described as “Undeclared Emergency” partly because the government doesn’t have to declare emergency officially, since self-censorship can be used as a potent weapon to silence any voice of dissent. Over the years, because of the free market and growing influence of the government and major political parties over the media industry, things have become easier. Earlier, the government had complete control over public broadcast services, besides which it was a major source of revenue for newspapers that relied on government advertisements and subsidised newsprint. With the growth of private channels, a remarkable change was noticed. Those in power found other means to wield influence over what people need to know. This was an era of corporate ownership of the media outlets. With the corporate world relying on the government for protection of business interests and their growing nexus with the policy makers belonging to major parties, the newsrooms lost their missionary zeal and contact with the people.

Modi came to power with a brute majority in 2014 under these circumstances. What separates him from his predecessors is the extreme right wing ideology of his party, which believes in totalitarianism and aspires to turn India into a monolithic Hindu theocracy which provides no room for dialogue and dissent. Modi has also centralized power, which has dried up sources of media outlets in the government, dissuading journalists from getting access to more critical voices within the state structure. Some recent examples are sufficient to prove this point.

Last year the Caravan magazine reported how a judge had died under mysterious circumstances after being offered a bribe to give a favourable verdict to save a BJP leader and close confidant of Modi, Amit Shah, who was instrumental behind an extra judicial murder of a Muslim man by the Gujarat Police. The big media channels of India largely ignored the story. So much so, that many of the media outlets were used to counter the story with alternative theories floated to save the government.

The recent one-on-one interviews given by Modi to Zee News and Times Now have also raised many questions. These interviews were framed in an “open-ended” way which allowed Modi to bring in information that the government wanted placed in the public domain. According to observers, both interviews followed a script and not surprisingly no hard hitting critical questions were asked.

The BJP has also raised an army of trolls who flood the social media with fake news stories. The matter does not end there. These trolls have been attacking credible journalists and using foul language to intimidate critics. Interestingly, some of them are being followed by Modi. These included an individual who created a controversy by rejoicing the murder of Gauri Lankesh on twitter. In fact, Lankesh in one of her final editorials had written about these trolls who have been spreading lies through fake news to create hatred against Muslims. She had well documented the cases of fake news stories in her editorial that might have triggered her murder.

The early signs of the impending assault on free expression started showing shortly after Modi was elected as Indian Prime Minister. In the South Indian state of Kerala, 13 students were arrested for mocking Modi in their college magazines. The students of one college were arrested for including him in the list of “negative faces”, such as Adolf Hitler, Osama Bin Laden, and George W. Bush. A comedy play named after the BJP’s election slogan “Ache Din Aane Wale Hain” (Happy days are coming) was banned in Chandigarh under pressure from BJP supporters. The play mocked the policies of the BJP government.

What does it mean for Canada?

There has been a feeling that this may spill over to Canada and the U.S., especially in areas with sizable South Asian communities.

As the pro-Modi lobby grew stronger, the muzzling of independent media voices within the South Asian diaspora began showing its signs. Modi was earlier denied entry by the U.S. because of his government’s complicity in the anti-Muslim pogrom in the state of Gujarat in 2002. Modi was chief minister of Gujarat when police allowed thousands of Muslims to be murdered by mobs led by Hindu fundamentalists. Following the change of guard in India after the last election, the U.S. welcomed Modi in September 2014.

That the Modi lobby may start exerting its pressure on the local South Asian media became evident on August 5, which was my last day as news broadcaster and talk-show host with Radio India. I was told by my former employer that we should start endorsing Modi’s proposed visit to the U.S. instead of giving voice to anyone who opposes it. The provocation was my live interview with the spokesman of Sikhs For Justice, which had launched a petition asking the U.S. government to cancel Modi’s visit. I was told that Sikhs For Justice supports a theocratic Sikh state and under no circumstances should such groups be given any kind of legitimacy.

I do not agree with the agenda of Sikhs For Justice, but being a journalist, I was only trying to give voice to a group that had launched an initiative on a very pressing issue. I had to explain that Modi’s proposed visit is not just being opposed by Sikhs For Justice but other non-Sikh activists too. But all my arguments fell on deaf ears. I was rather told that if I cannot do this, the nature of my duties can be changed. I therefore adamantly decided to quit rather than continue working there.

Although it was a difficult decision to leave an organization I served for the last 13 years, I have no regrets for saying ‘no’ to Modi. After giving much thought to what I have done, I decided to go public and make people aware of the threat of an undeclared censorship in India and its impact overseas. Because it’s not just my story, I decided that people should know. We all need to find what’s going on behind the curtains and how big powers continue to exert their pressure on media outlets even outside India, possibly through diplomatic and other non-official channels.

For me the bigger issue is a challenge coming from fascist forces that blatantly attack free expression under a right-wing government. All we need is a strong initiative against fascism and the sophisticated ways it uses to muzzle independent voices. With an idea of starting such an initiative, an emergency meeting was held in Surrey. Among those present was Tejinder Kaur, who was reportedly fired by Punjabi radio station Shere Punjab under similar circumstances. Sometime after this meeting we decided to hold a demonstration outside the Indian consulate in Vancouver. This was nearly blacked out by the South Asian media. A very prominent South Asian channel, Omni TV, sent its crew. They took the footage, but showed nothing on the bulletin.

In 2016, another journalist Shiv Inder Singh, who gave daily news updates from India to Red FM radio station in Surrey, was told that his services were being discontinued because of several complaints about his “negative” coverage of the Modi government. Though Red FM denied this, Singh went to the CRTC. While nothing came out of that, his complaint again exposed how strong pro Modi lobby in Canada is.

In 2017, I along with some activist friends had invited Rana Ayyub, a famous journalist from India, to talk about her investigative work in Gujarat. She had done a sting operation on anti-Muslim violence under Modi government. Based on her work, she published a book titled; “Gujarat Files”. We had requested the Ross Street Sikh temple in Vancouver to let her come to the temple and speak to the congregation about her work. Since this temple is run by the oldest Sikh body, which has a history of resistance against racism and the British occupation of India, we wanted Ayyub to be given a chance to connect with its congregation. But the temple management refused to let her speak citing her “controversial background”. Notably, this is the same temple that welcomed Modi in 2015. There was an angry demonstration against Modi when he came to the temple. Notably, this was blacked out by the media persons from India who accompanied Modi during his Canada visit. Recently, we have noticed how most South Asian media outlets continue to ignore protests in Vancouver against Modi’s government, and there is a deafening silence about growing religious intolerance in India.

A PTC news channel known to owe allegiance to the BJP and its coalition partner Akali Dal in Punjab, recently covered our rally seeking justice for victims of the 1984 anti-Sikh massacre engineered by the then-Congress government. Interestingly, the PTC coverage blacked out everything said by the speakers against the BJP. Only the statements against the opposition Congress party were covered in the news bulletin.

All this is happening because media people are scared that Indian government might deny them visa if they cover such issues. In the past several Indo Canadian journalists were denied visas while some were forced to return from Delhi airport. It is time that Canada should wake up and see what is going on in India. The belief that India is a strong democracy is a myth.

Unfortunately, our Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who just concluded his visit to India, remained silent on these issues. This is despite the fact that Canada claims to be a human rights leader in the world and many groups of South Asian activists across Canada tried to apprise him of the situation before he headed out to India through his MPs.

On the contrary he received bad press in India, largely under the influence of the Modi government that tried to portray his government as soft on Sikh separatists active in this country. Most Sikh groups seek the right to self-determination through propaganda, but the Modi government left no stone unturned to project Trudeau as an apologist of Sikh extremism, with an intention to polarize Hindu majority against the Sikhs who make merely two percent of the Indian population.

(This paper was read out at a panel discussion held at Vancouver Public Library on February 26 to mark Freedom to Read Week)

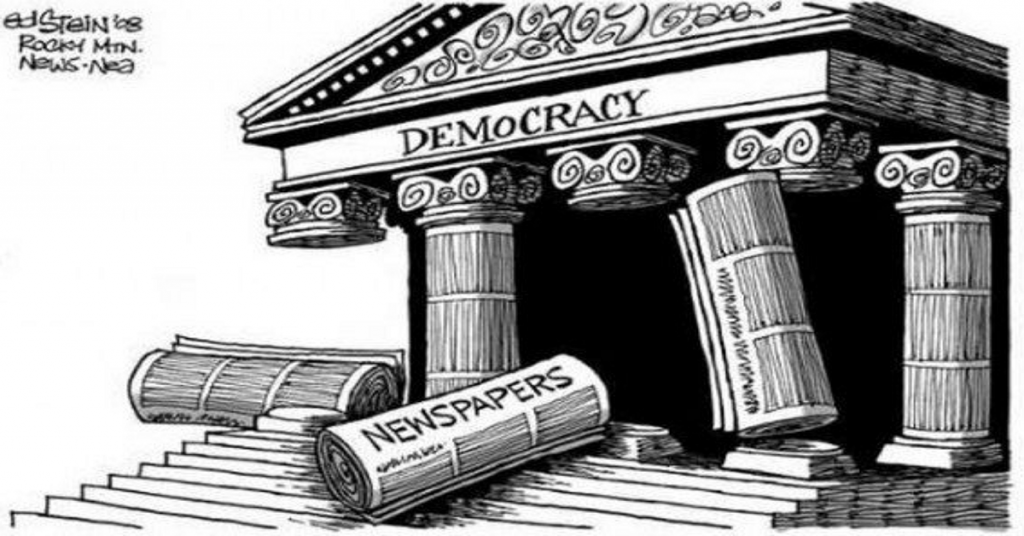

*** Feature Image by Ed Stein.