We are on a public stage at a high profile lit fest in the pristine and exclusive Delhi Gymkhana, home to the country’s ruling elite when an elderly gent gets up and harangues me: ‘I have been listening to you talk for the last half hour, you talk like an anti-national, we should throw you out from here!’ I have just been speaking on the need to revive the dialogue in Kashmir with all stakeholders and voiced my concern over stone-throwing and the growing distancing of the ‘aam aadmi’ in the valley from the political leadership. The organisers manage to control the situation before it gets ugly. My critic turns out to a retired senior army officer, a proud and honourable Indian citizen but one whose worldview has no time or mindspace to listen to any talk of human rights violations in the Valley.

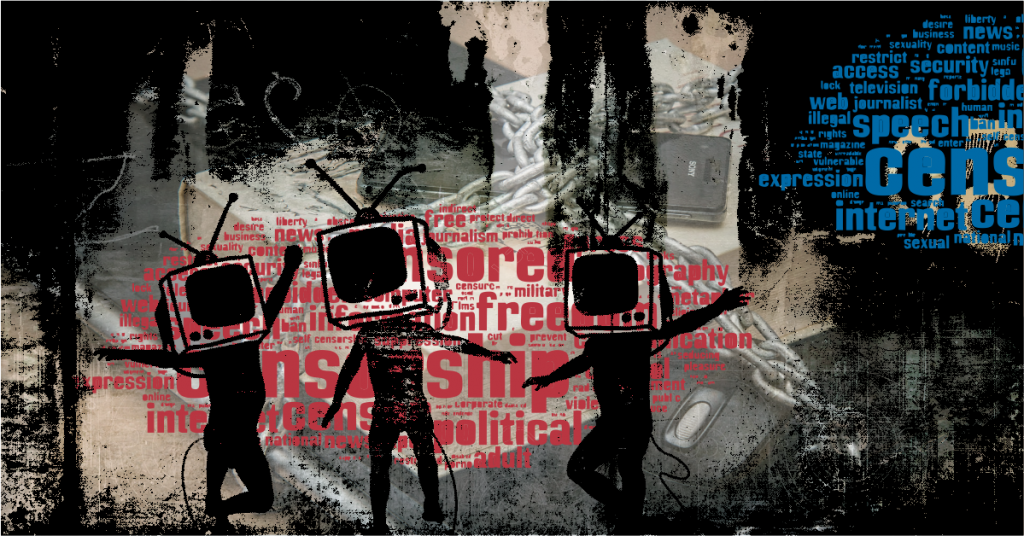

Those who advocate for human rights in conflict zones have always been targeted as ‘bleeding heart jholawallahs’. Now, a new word has been added to the divisive lexicon: ‘anti-national’. In an increasingly politically polarized climate, the narrative over human rights is now shaped in a toxic and frenzied manner that allows little space for a reasonable dialogue. When voicing concern over children who are being blinded by pellet guns is seen as treasonous, then it makes it very difficult to have any kind of engagement. The loud ‘nationalistic’ argument seeks to drown out all other voices, often shooting from the shoulders of anonymous men in uniform. Which is why when a Kashmiri is tied to a jeep and paraded in the street, no one is expected to question the army major who has taken the contentious call that is a blatant violation of human rights.

It is precisely this veil of silence that must be lifted: a strong nation must have the resilience and the capacity to confront inconvenient truths. These truths do not remain confined to just the Kashmir valley which, in a sense, remains the most visible symbol of the failure of the Indian state to find a human and just resolution to the anguish of its citizenry. But the 70 years of Indian independence are littered with instances where our republican

constitution has failed its people, where the rights and freedoms enshrined in our ‘holy book’ have been violated with impunity. In how many instances of riots and massacres in this country have we provided justice or any sense of closure to the victims of targeted violence? Then, be it atrocities against women, Dalits, tribals, minorities, farmers, the poor and the landless, how often has the Indian state stood firmly with the victim?

We in the media, especially TV media, have been just as culpable. In the whirl of TRPs, how much air-time do we give to issues like farmer suicides or labour unrest? Does a farmer who is being exploited by a ruthless money-lender have no rights as an Indian citizen? In the glamorous world of a TV studio, large parts of this country have literally become areas of darkness. We report from vast states like Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, for example, only when there is a Naxal attack and a dozen policemen are killed in an ambush. And even then, we will reduce a serious and complex issue to a shrill studio black and white false binary debate: either you are with the Indian state or else you must be targeted as an ‘anti-national’ leftist who is hand in glove with Maoists/terrorists.

Rajdeep Sardesai is a senior journalist and author.