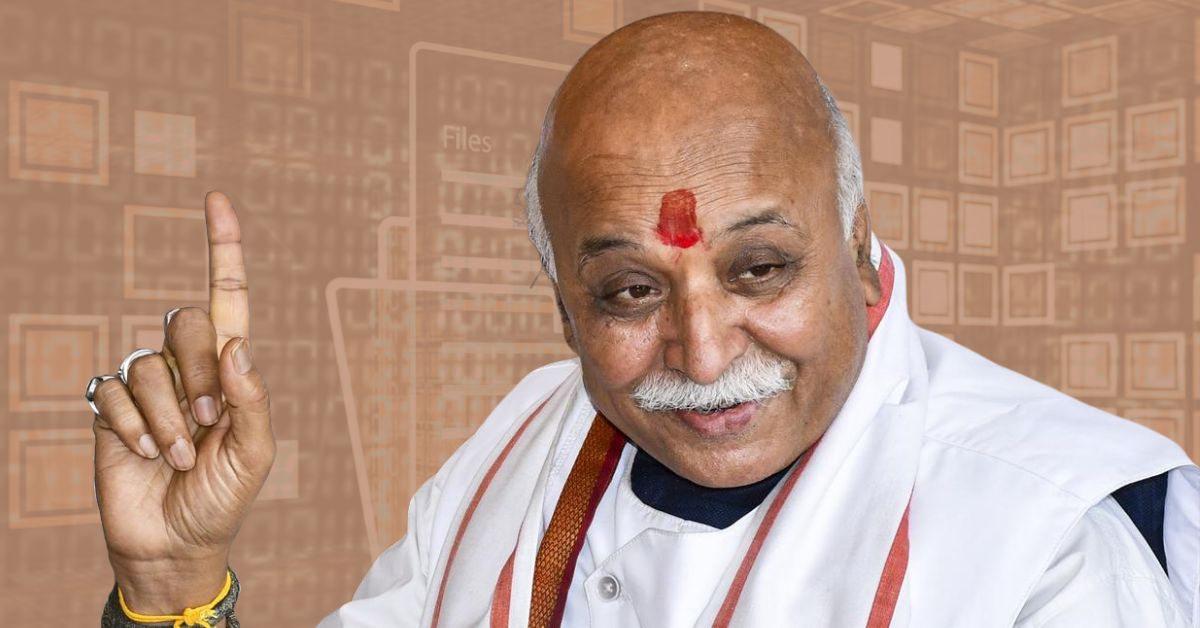

Over the past six months, across small-town maidans, temple courtyards, community halls, industrial clusters, and makeshift stages stretching from Uttar Pradesh to Gujarat, Assam to Maharashtra, a parallel political vocabulary has been unfolding—one that does not merely confront India’s constitutional imagination but seeks to overwrite it. At hundreds of events organised by the Praveen Togadia–led Antarrashtriya Hindu Parishad (AHP) and its youth wing, the Rashtriya Bajrang Dal (RBD), an alternative moral order was being scripted in real time: a world in which demographic suspicion becomes civic virtue, weapons become sacralised instruments of community defence, masculinity becomes the measure of citizenship, and minorities—especially Muslims and Christians—are recast as civilisational threats rather than equal members of the Republic. What emerges from this dataset is not a scattered chronicle of hate speech. It is a window into the systematic construction of a networked, organised architecture of majoritarian power—an apparatus that operates in the shadow of the state, thrives on institutional abdication, and gradually normalises a vigilante sovereignty that rivals the authority of the Constitution itself. The mysterious and rather inexplicable shift of Pravin Togadia from his decades’ long association with the original Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and Bajrang Dal (BD) also bears investigation!

While India has long witnessed episodic flashes of communal hostility or sporadic acts of vigilantism, the six-month period under study stands apart for its density, coordination, and geographic spread. Under Togadia’s polarising leadership, AHP and RBD conducted dozens of public rallies, Shastra Puja ceremonies, trishul and weapon distribution events, ideological training camps, anti-conversion protests, disruptions of minority religious gatherings, and direct interventions into interfaith and community life. The patterns revealed in these events are not incidental expressions of bigotry but components of a carefully structured ideological project that merges theology, masculinity, ritual, and violence into a coherent organisational strategy.

CJP is dedicated to finding and bringing to light instances of Hate Speech, so that the bigots propagating these venomous ideas can be unmasked and brought to justice. To learn more about our campaign against hate speech, please become a member. To support our initiatives, please donate now!

The socio-legal significance of this mobilisation lies not only in the content of the speeches or the frequency of the gatherings but in the formation of a parallel normative order—a majoritarian apparatus that increasingly shapes public life, community relations, and the distribution of violence. AHP–RBD’s activities represent the consolidation of what may be termed an infrastructural form of vigilante sovereignty. In this system, communal identity becomes the organising principle of public order; violence is reimagined as moral duty; masculinity becomes a civic ideal; and the state’s authority is supplemented—or overridden—by militant religiosity. This is not a spontaneous phenomenon. It is patterned, scripted, routinised, and embedded in organisational structures that grant it continuity, reproducibility, and diffusion.

This article examines the six-month mobilisation through a socio-legal lens, drawing from an extensive dataset of AHP–RBD events across multiple states (see attached document for a comprehensive list). By tracing thematic narratives, analysing rhetorical patterns, studying ritual practices, and observing the organisation’s interactions with state institutions—particularly the police—we demonstrate how AHP–RBD’s activities signal a dangerous reconfiguration of India’s democratic order. The mobilisation reveals the emergence of a dual authority structure: the formal, constitutional state that guarantees equality, liberty, and religious freedom, a constitutional order that is being hollowed out; and a parallel, extra-legal majoritarian sovereignty that polices interfaith intimacy, adjudicates religious legitimacy, regulates gender and sexuality, and authorises violence in the name of community protection.

The implications for constitutional democracy are profound. AHP–RBD’s activities challenge the secular and egalitarian commitments of the Constitution. More critically, they expose how these commitments are weakened not only through state action but through state inaction—through selective policing, tacit endorsement, rhetorical alignment, or the silent normalisation of extremist discourse. As hate becomes publicly permissible, minority communities experience shrinking civic space, and majoritarian aggression becomes an accepted instrument of social control.

From a social movement perspective, AHP–RBD functions as a radical flank within the wider Hindutva ecosystem. By expanding the boundaries of extreme speech and acceptable violence, it shifts the Overton window rightward and allows mainstream political actors to appear moderate while benefiting from the emotional climate generated by extremist mobilisation. From a legal standpoint, the group’s actions—ranging from hate speech and incitement to weapons handling and vigilantism—constitute repeated violations of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, the Arms Act, and fundamental constitutional rights.

This article argues that AHP–RBD’s mobilisation is not merely evidence of rising majoritarian aggression but an indication of a new mode of communal politics—one that fuses ritual, masculinity, religious symbolism, historical revisionism, and legal ambiguity into a potent political formation. It is both ideological and infrastructural, capable of generating continuity, producing cadres, shaping emotional climates, and influencing electoral behaviour. To understand its legal implications, we must move beyond individual violations and analyse the broader socio-legal transformation it represents: the gradual emergence of a parallel polity that threatens to displace constitutional democracy from within.

From VHP margins to radical extremist formation

Praveen Togadia, a trained cancer surgeon, entered the arena of Hindu nationalism through the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and subsequently rose to –or was ordained to–become the International Working President of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP). This period was his political crucible. He distinguished himself through militant cultural mobilisation, most notably the organisation of ‘Trishul Deeksha’ (trident distribution) ceremonies for Bajrang Dal activists, a direct act of communal provocation and arms dissemination that often-violated state bans.

The Bajrang Dal, the original youth wing of VHP, provided the blueprint for AHP-RBD’s operational tactics. Its foundational ideology—Hindutva, Islamophobia, and a far-right position—was perfected during the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the subsequent Gujarat pogrom of 2002, where Togadia’s influence was significant. For a previous and thorough analysis of Togadia’s antecedents and actions, see the May 2003 issue of Communalism Combat, Against the Law.[1] The Bajrang Dal legacy of violence and communal targeting, from anti-Christian attacks to ‘moral policing,’ is the exact ideological inheritance upon which the AHP-RBD is built.

The AHP-RBD is Togadia’s vehicle to claim his position as the authentic voice of uncompromising, hardline Hindutva. This background explains several features of AHP–RBD’s mobilisation:

- its rhetorical extremism, which goes beyond even the most polarising elements within mainstream Hindutva;

- its obsession with demographic fear and gender policing;

- its reliance on ritual militarisation as a means of identity formation;

- its disregard for legality and due process;

- and its strategic positioning as a radical flank to the BJP, indirectly reinforcing the latter’s political dominance.

AHP–RBD is a product of ideological intensification, organisational displacement, and the opportunities created by a political climate increasingly tolerant of majoritarian aggression. It thrives in the gaps between state authority and nationalist discourse—in the ambiguities of legal enforcement, the ambivalence of political leadership, and the anxieties of a society grappling with polarisation, insecurity, and historical grievance.

Hate as a structure- analysis of the pattern

The events analysed in this article consists of detailed descriptions of AHP–RBD events across India between April and November 2025. These events include rallies, speeches, religious ceremonies, festivals, weapons training camps, “awareness” drives, protests against minority institutions, processions, and interventions in local disputes. Each event contains descriptive information about the location, the nature of the activity, the content of speeches, the symbols deployed, the performative elements (such as tridents, swords, firearms), and the presence or absence of police.

Through this article, the events of the past six months are seen not as a collection of isolated incidents but as an aggregated structure—a corpus of political performance through which a particular vision of the nation, society, and citizenship is constructed and enacted.

Based on the data, a clear pattern emerges in the language and symbolic repertoire deployed across AHP events. Hate speech, in this context, must be understood not simply as verbal hostility but as a technique of discursive engineering—an organised method of drawing communal boundaries, allocating moral worth, identifying enemies, and legitimising forms of aggression. Across states and settings, the same tropes reappear with remarkable consistency: demographic panic, the spectre of “love jihad,” historical grievance, territorial loss, and civilisational threat. These are not spontaneous utterances but components of a deliberate ideological script crafted to evoke fear, shame, pride, and defensive anger in the audience.

Equally revealing is the ritualised dimension of the mobilisation. Ceremonies such as Shastra Puja, Trishul Deeksha, communal sword-blessing, or the devotional display of firearms function as much more than cultural performances. They represent attempts to sacralise violence by embedding it directly into religious and moral practice. When weapons are blessed, displayed, and circulated as objects of collective reverence, the boundary between devotion and aggression collapses. Drawing from anthropological work on ritual and theories of political religion, this analysis reads such events as performative acts that create a moral obligation toward vigilantism. They invite participants to imagine themselves not merely as believers but as defenders, making violence appear righteous and necessary.

The data also reveals how AHP–RBD positions itself as a source of extra-legal authority. In numerous instances, cadres assume functions associated with policing: intervening in interfaith relationships, raiding churches or prayer meetings, detaining individuals accused of “suspicious” behaviour, or monitoring localities under the guise of protection. Viewed through socio-legal theory, these actions are not isolated encroachments but indicators of a parallel governance structure. AHP effectively performs sovereign functions—identifying threats, enforcing discipline, and adjudicating moral transgressions—thus competing with the state’s monopoly over lawful coercion. Vigilantism here becomes a mode of rule, not an aberration.

Placed against constitutional and statutory frameworks, the significance of this pattern becomes sharper. The organisation’s rhetoric raises questions under hate-speech jurisprudence; its weaponised rituals potentially violate the Arms Act; its interventions into religious practice implicate Articles 25 and 26; and its targeting of Muslim and Christian communities challenges the equality guarantees of Articles 14 and 15. The concern is not the presence of individual violations but the cumulative erosion of constitutional norms they represent. As such practices become normalised, the protective architecture of fundamental rights weakens, and the boundaries between state authority and majoritarian desire blur.

Seen through the lens of social movement theory, this mobilisation aligns with what many term a radical flank: an extremist wing of a broader ideological ecosystem that shifts public norms by expanding the limits of permissible discourse. AHP’s open hostility, explicit calls for social segregation, and sacralised vigilantism create a climate in which mainstream political actors appear moderate even as they move closer to majoritarian positions. The dataset illustrates how such fringe rhetoric does not remain at the edges but gradually migrates toward the centre of political common sense, fuelling polarisation and recalibrating the moral thresholds of democratic life.

The analysis therefore treats hate not as a series of discrete incidents but as a structure—an enduring architecture embedded in speech, ritual, space, and authority. Mobilisation is read as a continuous process of meaning-making, one that is inseparable from legality, identity, and the distribution of state power. Recurrent performances of communal hostility gradually establish new baselines for what counts as acceptable public behaviour, shifting social norms long before laws change. At the same time, the analysis foregrounds how extra-legal actors strategically exploit legal ambiguities and enforcement gaps to assert control over public space, intimate life, religious practice, and everyday social relations. In this view, hate operates both as discourse and governance, reshaping the moral and constitutional landscape from below.

- Majoritarianism, vigilante sovereignty, and the production of fear

To understand AHP–RBD’s mobilisation based on the data, the organisation must be placed within three key theoretical perspectives: majoritarian nationalism, vigilante sovereignty, and the politics of fear. Majoritarian nationalism describes systems where one religious or ethnic community is treated as the true owner of the nation, while minorities are viewed as conditional members or potential threats. This framework aligns closely with AHP–RBD’s speeches, which repeatedly frame India as a Hindu nation and portray Muslims and Christians as outsiders who must be monitored or restrained.

The idea of vigilante sovereignty helps explain how non-state groups act like extensions of the state. Such groups enforce moral rules, police communities, intervene in personal relationships, and sometimes use or threaten violence. AHP–RBD’s raids, detentions, and street-level interventions fit this pattern, challenging the state’s exclusive right to use force and maintain public order.

The politics of fear shows how movements rely on fear not only as an emotion but as a tool of mobilisation. By invoking demographic threats, “love jihad,” religious conversion conspiracies, and historic betrayals, AHP–RBD creates an atmosphere of danger that makes aggressive action seem justified. Fear becomes the glue that binds supporters together and the justification for exceptional attitudes and behaviours.

In a one-sided political vacuum where the Opposition is yet to come up with a convincing, consistent and effective response to all the hyper claims made in hate speeches unleashed –be it on “demographic fear”, the “communal regulation of intimacy”, “ritual militarisation” and strong, street-level enforcement(s) of the rule of law, this vigilantism goes unchecked.

2. The politics of demographic fear

Demographic fear sits at the heart of AHP–RBD’s mobilisation strategy. Across the six-month dataset, leaders repeatedly promote the idea that Hindus are on the verge of becoming a minority and that Muslims are growing in number with deliberate, strategic intent. This narrative is presented as unquestionable fact. It relies less on evidence and more on repetition, emotion, and imagery: Muslims are described as multiplying rapidly, expanding territorially, organising politically, and threatening the very survival of the nation.

Although demographic anxiety has long existed within Hindu nationalist thought, AHP–RBD deploys it with unusual intensity and uniformity. Whether speaking in Ahmedabad, rural Maharashtra, small towns in Uttar Pradesh, or border districts in Assam, leaders use almost the same script: Hindus are shrinking; Muslims are taking over land; demographic imbalance will end Hindu civilisation; Muslim “vote banks” control politics; and Hindu women face imminent danger. The consistency of this message across regions reveals a coordinated ideological project rather than scattered local sentiment.

Viewed through a socio-legal lens, demographic fear acts as a political tool. It creates a sense of permanent emergency, shaping the present through imagined threats from the future. In this atmosphere, constitutional norms appear inadequate. Hate speech is reframed as a “warning,” weapons training becomes “protection,” and vigilantism is cast as “preventive action.” Even constitutional equality is portrayed as a risk Hindus can no longer afford.

Demographic fear also becomes a way of mapping territory. Several speeches describe Muslim-majority areas as “occupied zones,” “mini-Pakistans,” or “Bangladeshi territories.” This transforms ordinary patterns of residence or work into symbols of invasion. A Muslim neighbourhood becomes hostile territory; daily life becomes evidence of encroachment.

Socially, demographic fear collapses individuals into a threatening collective. A Muslim child becomes a sign of “population jihad,” a Muslim family becomes a plan of conquest, and a Muslim locality becomes a base of expansion. This removes any possibility of seeing Muslims as citizens or neighbours. They are recast as demographic threats, not people. Such dehumanisation makes discriminatory acts or violence appear justified.

At the same time, demographic fear reshapes Hindu identity. It portrays Hindus as vulnerable and under siege, encourages men to adopt a protector role, and frames women as symbols of community honour. This narrative helps unify diverse Hindu groups around a shared sense of danger and duty. In speech after speech, AHP leaders ask Hindus to “wake up,” “stay alert,” and “prepare for struggle.” Fear becomes a tool for building collective identity.

Legally, demographic fear is not just misleading—it is harmful. It fuels discrimination, normalises exclusion, and creates justification for violence. Indian constitutional law, especially in hate speech cases such as Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan (2014) and Amish Devgan (2020), makes clear that speech portraying an entire community as dangerous violates equality, dignity, and public order. Yet at many AHP–RBD events, police and local authorities stand by, signalling that such rhetoric is tolerated. This gap between constitutional protection and on-ground practice allows demographic fear to circulate freely and take root in public life.

In the end, demographic fear is the foundation on which AHP–RBD’s entire mobilisation rests. It casts Muslims as permanent adversaries, turns reproduction into a battleground, and provides justification for weapons rituals, gender policing, vigilantism, and calls for segregation or violence. Without demographic fear, much of AHP’s narrative loses force. With it, almost any action becomes thinkable.

3. Gender, sexuality, and the communal regulation of intimacy

Gender and sexuality lie at the centre of AHP–RBD’s ideological project. Although the organisation claims to defend “Hindu dharma” and “protect Hindu women,” its speeches reveal a deeply patriarchal, hyper-masculine, and communal vision in which women’s bodies and choices are controlled in the name of community honour. The conspiracy theory of “love jihad”—the claim that Muslim men intentionally form relationships with Hindu women to convert them and weaken Hindu society—functions as the main tool for this control.

Nearly half the events in the data refer directly to “love jihad.” This is not accidental. It reflects a worldview in which gender becomes the most important site of communal conflict. Hindu women are portrayed as innocent, gullible, and easily manipulated. Muslim men are cast as predatory, cunning, and hypersexual. This binary has no factual basis, but it is designed to justify constant vigilance, suspicion, and hostility.

Within AHP–RBD’s discourse, the Hindu woman is not treated as an autonomous individual with constitutional rights. Instead, she is imagined as the carrier of Hindu lineage and the symbol of community purity. Her body becomes communal property; her relationships are judged through the lens of demographic threat. Any interfaith relationship is interpreted as coercive by default. By denying Hindu women agency, the organisation turns them into objects of protection rather than subjects of choice.

This framework produces three major socio-legal consequences.

- First, it legitimises the surveillance of women. AHP–RBD members monitor public spaces—markets, colleges, workplaces—to watch interactions between Hindu women and Muslim men. Their presence creates an environment of constant scrutiny. Hindu women become boundary markers rather than free citizens, their mobility and friendships policed in the name of protection.

- Second, it encourages violence against Muslim men. In many speeches, Muslim men are presented as inherent threats, and audiences are urged to confront, punish, or even kill them. Such rhetoric directly violates the BNS and constitutional guarantees of equality and personal liberty. Yet these statements are made openly, often with police present, signalling that communal violence in the name of gender protection is tolerated.

- Third, this discourse undermines constitutional rights. The Supreme Court in Hadiya affirmed that adults are free to choose their partners. Judgments in Shafin Jahan, Navtej Johar, and Puttaswamy recognise autonomy, dignity, and privacy as core constitutional values. AHP–RBD’s mobilisation, however, replaces individual autonomy with communal control. Interfaith relationships are reframed as conspiracies, and constitutional protections are cast as threats to Hindu survival.

Sociologically, this gendered narrative binds Hindu men together through a shared sense of masculine duty. The call to protect Hindu women becomes a mechanism for creating solidarity among Hindu men. Masculinity is defined in militarised terms—strength, vigilance, and readiness for confrontation. Rituals such as weapon worship or trishul distribution reinforce this ideal. In effect, gender becomes a tool for producing a community of men primed for conflict.

“Love jihad” is therefore not only a myth or a political slogan. It is a central organising principle of AHP–RBD’s mobilisation. It regulates women’s autonomy, fuels hostility against Muslim men, strengthens group identity, and provides moral justification for vigilante action. It transforms everyday intimacy into a battleground and reimagines private relationships as matters of communal survival.

4. Ritual militarisation and the sacralisation of violence

One of the most notable features of AHP–RBD’s mobilisation is the central role of ritual in normalising violence. The dataset records numerous events involving Shastra Puja (weapon worship), Trishul Deeksha (the distribution of tridents), firearm training sessions, self-defence workshops, and public displays of swords, guns, and tridents. These are not decorative additions to political gatherings. They form the core of the organisation’s ideological strategy.

Shastra Puja, traditionally a religious ritual, is given a distinctly political meaning in AHP–RBD events. In Togadia’s speeches, weapons are celebrated not for their symbolism but for their function: the ability to defend the Hindu community through force. Swords stand for courage, tridents for purity, and guns for preparedness. When weapons are blessed, violence itself is blessed. The ritual frame offers moral cover for aggression, allowing political intent to hide behind religious practice.

Trishul Deeksha takes this further. Distributing tridents to young men is presented as a religious initiation, but it effectively creates a pool of recruits marked as “defenders of Dharma.” These tridents act as identity symbols—visible signs of readiness for confrontation. Such initiation rituals resemble practices used by militant groups in other contexts, where symbolic objects bind participants emotionally to the idea of collective struggle.

The presence of firearm training raises serious legal concerns. Under the Arms Act, handling or training with weapons requires strict permissions. Yet AHP–RBD frequently holds such sessions in public, often without police objection. Firearm training serves two purposes: it teaches practical skills and signals that the organisation sees itself as a force parallel to the state. It implies that AHP–RBD does not accept the state’s monopoly over violence.

From a sociological perspective, these rituals work to create a sense of community built around aggression. They produce male-dominated spaces where violence is sanctified, celebrated, and practiced. Religious devotion merges with militant nationalism, creating what scholars call a “sacralised polity”—a political identity shaped through ritualised displays of strength and readiness for conflict.

The socio-legal implications are far-reaching. Ritual militarisation dissolves boundaries between religion and politics, symbolism and force, legality and illegality. It creates a community that believes it has a moral right—perhaps even an obligation—to act outside the law. Weapons become sacred objects, violence becomes a communal act, and vigilantism becomes a perceived duty. In doing so, these rituals undermine the fundamental principle that only the state may use legitimate force, eroding a key pillar of constitutional democracy.

5. Territorial mythology, historical revisionism, and the spatialisation of hate

A key feature of AHP–RBD’s mobilisation is the way it reimagines geography and history through a communal lens. The organisation does not limit itself to present-day political disputes; it draws from a broad mix of mythologised history, civilisational claims, and territorial grievance. This revisionism is not merely cultural. It is a strategic attempt to redefine who belongs to the nation, who owns its land, and who has moral authority over its public and sacred spaces. Claims that global religious sites—Mecca, Medina, the Vatican—were once Hindu temples are historically baseless, but they serve an ideological purpose. They create a narrative in which Hindu civilisation is the original owner of sacred geography, and Islam and Christianity are portrayed as late, intrusive forces that took what was not theirs.

This worldview forms the core of AHP’s political theology. Hinduism is framed as the world’s first civilisation and the rightful custodian of global sacred space. Muslims and Christians are described as foreign arrivals, civilisational disturbers, and historical invaders. This racialised framing attempts to detach Indian Muslims and Christians from national belonging itself. If even Mecca is described as stolen Hindu territory, the implication is clear: if global Islamic spaces are illegitimate, then Indian Muslims’ connection to India is even more fragile.

These ideas have concrete socio-legal effects. Outlandish territorial claims become the basis for communal mobilisation. The demand to “reclaim” Kashi or Mathura is not an isolated argument about specific temples; it rests on a broader theory that all Muslim religious structures were built on destroyed Hindu sites. Mosques are reframed as symbols of past defeat. Muslim presence becomes a reminder of humiliation. Violence, in this worldview, becomes not aggression but restitution—an attempt to “correct history.”

This spatial politics is reinforced by emotionally charged language. Muslims are frequently described as “occupiers,” “encroachers,” “land-grabbers,” “Bangladeshis,” or “jihadi settlers.” These labels turn ordinary residential areas into imagined battlegrounds. Citizenship becomes a form of occupancy, always at risk of being revoked. In cities like Ahmedabad and Vadodara, leaders claim that Muslim-majority areas function as “no-go zones,” suggesting that the state has lost control over its own territory. Even though such claims lack factual basis, they generate territorial fear—a sense that Hindus are losing physical ground within their own homeland.

AHP’s territorial imagination therefore operates as a project of remaking India’s social geography. It asserts Hindu ownership over land, temples, cultural memory, and even urban space. It calls for active “reclaiming,” often framed as a religious duty. Ayodhya is invoked repeatedly as proof that reclamation is both possible and necessary; from this starting point, Kashi, Mathura, and numerous other sites are presented as the next steps in a never-ending civilisational project. The logic then extends beyond religious sites to entire regions. Districts in Assam, border areas in West Bengal, and parts of Uttar Pradesh or Karnataka are portrayed as “Hindu land under occupation.”

This mythologised re-territorialisation creates an atmosphere where violence becomes spatially authorised. Areas labelled as “occupied” become legitimate targets. Local Muslim communities are cast as heirs of historical invaders. Calls for “ghar wapsi” (re-conversion) sit alongside calls for the physical return of land and shrines. Space itself becomes a tool for asserting dominance.

Constitutionally, this spatialised rhetoric cuts at the heart of India’s secular framework. It undermines equal citizenship, freedom of religion, and the principle that every person belongs to the nation regardless of ancestry or historical claims. The Constitution does not recognise civilisational ownership as a basis for citizenship or territorial rights. Yet AHP’s vision creates precisely this hierarchy, reducing minorities to conditional members whose belonging is always in question.

By turning geography into ideology and history into grievance, AHP reshapes the everyday landscape of citizenship. Places where Muslims live, work, study, or pray are reframed as contested space. The symbolic “reclaiming” of Ayodhya, Kashi, and Mathura becomes a template for local domination. In this way, territorial mythology becomes a form of mobilisation, transforming public space into a site of communal assertion and fear.

6. Vigilante sovereignty and the emergence of extra-legal authority

A striking pattern across the six-month dataset is AHP–RBD’s routine assumption of policing powers in public life. The organisation intervenes in interfaith relationships, raids Christian prayer meetings, stops or disrupts mosque construction, questions Muslim men in public spaces, conducts anti-conversion patrols, and targets activities it labels as threats to “Hindu interests.” These are not isolated excesses. Together, they form a consistent system of vigilante sovereignty—where a non-state group exercises coercive authority normally held by the state. The singular impunity enjoyed by them is reflected in the wilful inaction of the police and administration wherever such rallies are/may be held.

Vigilante sovereignty describes situations in which the state’s exclusive control over violence weakens, and ideological groups step in to enforce their own moral and communal rules. AHP–RBD does not simply break the law; it creates an alternative legal order grounded in majoritarian claims rather than constitutional principles. Under this order, minorities are treated as security risks, women’s choices are subject to policing, and dissent becomes dangerous.

This vigilante order is maintained through three connected practices: surveillance, intervention, and punishment.

- Surveillance involves monitoring interfaith couples, tracking alleged conversions, observing the building or renovation of mosques, keeping watch on Muslim-owned businesses, and noting “suspicious” gatherings. This is not state surveillance—it is community surveillance. AHP cadres patrol local areas, monitor social media, gather information through informal networks, and maintain lists of individuals labelled as threats. Public safety is redefined to mean Hindu security; the presence of Muslims is framed as danger.

- Intervention is the next step. AHP–RBD members frequently enter private or semi-private spaces—homes, shops, churches, prayer halls, schools—to stop activities they see as harmful. These interventions often occur in the presence of police. In many events, police officers accompany AHP cadres when confronting interfaith couples or disrupting prayer meetings. The police rarely intervene to protect constitutional rights. This signals a breakdown of state neutrality and a sharing of authority between state and vigilante actors.

- Punishment is the final mechanism. Punishment may take the form of threats, public shaming, calls for economic boycotts, harassment, or physical assault. In several speeches, AHP leaders openly call for killing Muslim men accused of forming relationships with Hindu women. Such statements amount to direct criminal incitement, yet legal action is rare or non-existent. This impunity reinforces the belief that AHP is entitled to enforce its own version of justice.

The growth of vigilante sovereignty signals a larger transformation in India’s political culture: the emergence of a dual legal order. One order is constitutional, grounded in equality, dignity, personal liberty, and religious freedom. The other is majoritarian, grounded in identity, hierarchy, and demographic fear. AHP–RBD’s activities show that in many contexts, the majoritarian order is beginning to overshadow the constitutional one.

This shift carries serious jurisprudential consequences. The Constitution assumes that the state alone protects rights and wields legitimate force. When non-state actors take on state functions—raiding, interrogating, disciplining—without consequence, the constitutional promise collapses. What emerges is a patchwork of informal jurisdictions where constitutional rights are selectively enforced or suspended. These are not declared emergencies; they are silent, everyday suspensions made possible by police complicity, public fear, and the normalisation of hate.

This pattern is not unique to India. Similar dynamics have appeared in other democracies under strain: paramilitary groups in Colombia, extremist Buddhist groups in Myanmar, anti-Muslim vigilantes in Sri Lanka, and evangelical militias in Brazil. In each case, vigilante sovereignty grew when governments aligned themselves with majoritarian ideologies, allowing the line between state and militia to blur.

AHP–RBD’s actions place India on a comparable path. By intervening in relationships, the organisation claims control over personal freedom. By stopping prayer meetings, it claims control over religious expression. By patrolling public spaces, it claims control over visibility and movement. Through weapons training and youth mobilisation, it claims control over violence itself.

The consequences are profound. Vigilante sovereignty normalises discrimination, encourages extremism, weakens formal policing, and turns public space into a site of communal conflict. It reduces minority communities to conditional citizens whose rights depend on majoritarian approval. And it undermines constitutional remedies, because the harm is inflicted not directly by the state but by private actors operating with state tolerance.

The rise of this parallel authority may be one of the most serious threats facing India’s constitutional democracy today. It is not a temporary disruption. It is a developing system of governance—one that allocates coercive power along communal lines and embeds majoritarian dominance into everyday life.

7. The expansion of hostility toward Christians

Although Muslims remain the primary focus of AHP–RBD’s mobilisation, the dataset shows a clear and growing hostility toward Christians. This appears in speeches, protests against churches, disruptions of prayer meetings, accusations of forced conversion, and repeated rhetorical attacks on Christian institutions. The widening of the “enemy” category—from Muslims alone to Muslims and Christians together—signals a broader ideological ambition: the construction of a multi-target hate regime capable of policing all religious minorities under a single civilisational narrative.

The language used against Christians differs in content but mirrors the structure of anti-Muslim rhetoric. Muslims are portrayed as demographic threats; Christians as conversion threats. Muslims are framed as territorial and violent; Christians as deceptive and manipulative. Muslims are labelled infiltrators; Christians are labelled converters. Both sets of stereotypes reduce entire communities to singular, hostile identities serving a supposed anti-Hindu agenda.

This hostility toward Christians draws from a long-standing theme in Hindu nationalist thought. Since the colonial period, Christian missionaries have been depicted as foreign agents seeking to weaken Hindu culture through conversion. AHP–RBD revives this suspicion and blends it with contemporary anxieties about globalisation. Small prayer gatherings are described as “conversion factories,” and Christian charities are accused of hiding evangelism behind social service. Christian organisations are framed as part of a global conspiracy to destabilise India.

In multiple documented incidents, AHP members raided modest prayer meetings—often held in private homes or rented halls. These gatherings involved small groups reading scripture or singing hymns. Yet AHP cadres portrayed them as illegal conversion activities, despite any evidence. In some cases, police stood by silently or cooperated with the vigilantes. This produces a chilling effect: ordinary Christians fear harassment simply for assembling to pray.

Such acts strike at the heart of Article 25 of the Constitution, which protects the freedom to practise and profess religion. While propagation may be regulated, peaceful prayer cannot be criminalised. AHP’s interventions amount to an informal ban on Christian worship, undermining both religious freedom and equal citizenship.

At a strategic level, anti-Christian rhetoric helps AHP broaden its reach. By depicting Christians as agents of foreign powers, the organisation taps into nationalist anxieties about global influence and cultural loss. This narrative complements anti-Muslim fear: one enemy threatens demographics; the other threatens culture. Together, they create a sense of constant siege and justify continuous mobilisation. Unlike anti-Muslim mobilisation, which is often localised, anti-Christian mobilisation can be deployed even where Christians are few, giving AHP a tool for organising in diverse regions.

This has political effects as well. Christian communities often support opposition parties in states like Kerala, Goa, and parts of the Northeast. Intimidating these communities weakens their political engagement, reduces turnout, and disrupts civil society networks. Fear becomes a quiet form of electoral influence.

The hostility toward Christians is therefore not a minor extension of communal rhetoric. It reflects an attempt to define Indian identity through exclusion—to construct Hindu majoritarianism as the only legitimate form of belonging. In such a framework, constitutional rights become conditional, minority presence becomes suspect, and religious freedom exists more on paper than in daily life.

By targeting both Muslims and Christians, AHP–RBD is building a broader authoritarian cultural order. This multi-target hate regime claims the power to decide which religions are acceptable, whose practices are legitimate, and whose presence is a threat. It marks a deepening of communal authoritarianism in contemporary India—one that endangers minority rights and undermines the secular, democratic foundations of the Constitution.

The Regional Geography of Mobilisation: Spatial clusters, localised idioms, and the federal life of hate

The six-month dataset shows that AHP–RBD’s mobilisation is not uniform across India. It is spatially strategic. Events cluster in states where demographic anxieties, political incentives, and weak institutional checks come together. Each state reveals a distinct pattern of hate mobilisation, shaped by its own history, politics, and social structure.

Uttar Pradesh is the epicentre. The volume and aggression of AHP–RBD events are highest here. UP’s large Muslim population, history of communal violence, and increasingly majoritarian state machinery create a permissive environment. Leaders use UP platforms to deliver the most direct threats—calling for violence, monitoring interfaith couples, and enforcing social boycotts. Police often stand alongside AHP speakers, giving hate speech an aura of official sanction. In UP, the line between state power and vigilante action is blurred.

Gujarat functions as the ideological centre. Many of Togadia’s longest, most doctrinal speeches—on demographic war, civilisational supremacy, and global conspiracies—are delivered here. Gujarat’s political ecosystem, shaped by 2002 and deep institutional alignment with Hindutva, enables a more elaborate and ritualised form of mobilisation. The tone is less about street-level confrontation and more about sweeping historical claims and grand narratives of Hindu civilisation.

Maharashtra shows a dual pattern. In cities like Mumbai, Thane, and Pune, AHP focuses on rhetoric of “security,” appealing to middle-class anxieties. In semi-urban and rural belts—Jalgaon, Nashik, Dhule, Vidarbha—mobilisation becomes more militant, involving trishul distribution, Shastra Puja, and weapons demonstrations. Shivaji iconography and Maratha pride blend easily with AHP’s narrative of Hindu power and historical grievance.

Assam presents a different dynamic. Here, AHP taps into long-standing regional fears around migration and citizenship. The rhetoric of “Bangladeshi infiltration” dominates. Muslims of Bengali origin are framed as illegal occupiers rather than religious minorities. AHP simply amplifies anxieties already sharpened by the NRC, Foreigners Tribunals, and decades of political debate. The result is a powerful fusion of local ethnic fears and national Hindutva narratives.

Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Rajasthan serve as logistical hubs. These states host training camps, weapons rituals, and “awareness” programmes. The geography—forests, small towns, dispersed settlements—allows AHP to conduct paramilitary-style activities away from media scrutiny. The events may be less dramatic, but they are organisationally vital, producing cadres, distributing weapons, and building networks.

In Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, and Jammu, the mobilisation takes on distinct urban and border-specific tones. Delhi and NCR adopt a language of “national security,” framing hate as patriotism. Punjab’s smaller mobilisation focuses on anti-conversion rhetoric targeting Christian communities. In Jammu, AHP flattens the region’s complex social fabric into a simple Hindu–Muslim divide, feeding nationalistic grievance.

Taken together, these regional patterns show that AHP–RBD does not operate through a single model of mobilisation. It adapts to local fears, political opportunities, and cultural idioms. It can present itself as a militant outfit in one state, a cultural organisation in another, a devotional group elsewhere, or a community policing force where it faces little resistance. This spatial flexibility gives the organisation resilience and reach. It allows hate politics to be localised, normalised, and embedded in everyday life.

Understanding this spatial architecture is essential. It reveals that AHP–RBD is not just an ideological movement but a multi-scalar ecosystem—national in message, regional in form, and local in execution. This adaptability is what makes it both potent and difficult to regulate through conventional legal and administrative frameworks.

Electoral effects and the radical flank mechanism

AHP–RBD’s six-month mobilisation cannot be understood in isolation from India’s electoral landscape. Although the organisation is not seen formally part of the BJP–RSS structure, its activities consistently reinforce the BJP’s broader political strategy. Real and organisational connections also probably exist though these have not been publicly flaunted. The relationship is best explained through the “radical flank effect”—a social movement theory concept that describes how extremist groups shift public norms, allowing more “moderate” groups to appear reasonable while advancing a shared ideological agenda.

In practice, AHP–RBD performs the role of the radical flank. Its open calls for violence, its vigilante actions, and its demonisation of minorities create a political climate saturated with fear. Once such fear becomes ambient, the BJP’s own rhetoric—often couched in coded terms—appears centrist in comparison. When AHP demands expulsion of Muslims from certain areas, the BJP’s policies of strict policing or exclusionary welfare seem moderate. When AHP–RBD cadres raid prayer gatherings or harass interfaith couples, the BJP’s strong law-and-order posturing appears lawful rather than coercive. This triangulation enables the BJP to benefit from the emotional climate created by extremism without openly endorsing it.

Electoral data and field patterns show that regions with intense AHP–RBD activity often see heightened Hindu electoral consolidation. This shift does not require explicit coordination. It arises organically from the affective environment created by sustained hate mobilisation. When public discourse is filled with messages of demographic threat, “love jihad,” conversions, or “jihadist infiltration,” voters gravitate toward the party they perceive as the defender of Hindu security. Fear becomes the emotional engine of communal voting.

AHP–RBD’s activities also directly affect minority political participation. The intimidation of Muslim and Christian communities suppresses voter turnout, discourages public meetings, and deters grassroots organising. In regions with politically active Christian electorates—such as Goa, Kerala, Mizoram, and parts of the Northeast—the targeting of prayer gatherings and church-related activities has measurable political consequences. Fear reduces both visibility and voice.

The organisation also shapes elections by dominating local discourse. Its rallies receive disproportionate coverage in local media, creating a sense of tension even where none existed. Communal narratives crowd out issues like unemployment, inflation, agrarian distress, and welfare delivery. Once the baseline of public conversation shifts, secular concerns struggle to regain ground. Elections become referendums on identity rather than governance.

Finally, AHP–RBD acts as an ideological incubator. Themes it promotes aggressively—population control laws, campaigns against conversions, temple “reclamation,” policing of interfaith relationships—often migrate into mainstream party agendas or media debates. The journey from fringe to centre is gradual but unmistakable. Over time, these ideas stop appearing extreme and begin to seem like common sense.

The cumulative effect is a rightward shift of the entire political spectrum. Opposition parties find themselves forced to respond to issues defined by extremist actors. Centrist figures adopt majoritarian language to avoid appearing “anti-Hindu.” The space for dissent contracts. Minority political participation shrinks. Hate normalises itself within democratic life.

In this way, AHP–RBD’s impact is not limited to specific constituencies or elections. It reshapes the broader architecture of electoral politics. It alters what counts as legitimate speech, permissible demands, and acceptable public sentiment. It reconfigures the emotional and ideological terrain on which elections are fought. It changes the grammar of Indian democracy.

Legal Analysis: Hate speech, vigilantism, arms violations, and constitutional breaches

The six-month dataset reveals a consistent pattern of conduct that amounts to repeated, systemic, and often explicit violations of Indian criminal law and constitutional guarantees. These are not accidental excesses or spontaneous eruptions; they are central to AHP–RBD’s mode of mobilisation. Understanding their legal significance requires situating them within four frameworks: (1) hate speech and criminal incitement under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), (2) vigilantism and due process violations, (3) illegal weapons display and training under the Arms Act, and (4) breaches of fundamental rights under the Constitution.

Hate speech and incitement: Indian hate speech jurisprudence—through Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan, Amish Devgan, S. Rangarajan, and the Delhi High Court’s rulings on inflammatory rhetoric—draws a clear distinction between offensive speech and speech that actively threatens public order or incites enmity. AHP–RBD’s rhetoric consistently falls in the latter category.

Statements urging violence against Muslim men, portraying Muslims as territorial invaders, or suggesting that Hindu women are targets of organised conspiracies constitute direct criminal incitement. Allegations that Muslims intend to “capture territory,” “eradicate Hindu civilisation,” or “control Hindu women” invoke the exact categories of prohibited speech under BNS provisions relating to public tranquillity and enmity between groups.

The dataset reveals a striking enforcement vacuum. Police presence at events where this rhetoric is openly delivered suggests not neutrality but deliberate non-enforcement. This institutional reluctance enables the normalisation of hate—from legal violation to public common sense—and marks a failure of the state’s constitutional obligation to ensure equal protection of the law.

Vigilantism and violations of due process: AHP–RBD repeatedly assumes policing functions: detaining individuals, interrogating alleged offenders, conducting raids on prayer gatherings, and enforcing communal boundaries. These actions strike at the core of Articles 21 and 22, which guarantee personal liberty and protection from arbitrary detention.

The Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in Tehseen Poonawalla (2018) imposes a positive duty on the state to prevent vigilante violence and prosecute perpetrators. Yet the dataset shows the opposite pattern—police inaction, presence without intervention, and in some cases, tacit collaboration. This creates a regime of dual policing:

- one legal, constitutional, and equal (in principle);

- the other informal, communal, and majoritarian (in practice).

Such a regime violates the constitutional commitment to secularism and the rule of law—principles recognised as part of the Basic Structure Doctrine. Vigilantism thus becomes not merely unlawful conduct but a challenge to constitutional sovereignty itself.

Illegal weapons display and training: AHP–RBD’s mobilisation features widespread use of weapons—swords, tridents, and firearms—through Shastra Puja, Trishul Deeksha, public marches, and explicit weapons training camps. Under the Arms Act, the display of many of these weapons in public or the provision of combat training requires stringent licensing.

The documented events violate these norms on multiple fronts. Weapons are not incidental accessories—they are ritual objects, identity markers, and instruments of political signalling. The religious consecration of weapons grants moral cover to acts that would otherwise attract immediate criminal sanction.

The legal concern is compounded by state inaction. When police stand by as weapons are worshipped, circulated, or used in training sessions, the constitutional principle that the state holds the exclusive right to deploy legitimate force becomes diluted. India’s long-standing policy of keeping arms out of civilian political mobilisation begins to erode, replaced by a permissive environment for private militias.

Violations of fundamental rights: The cumulative effect of AHP–RBD’s actions is a sustained infringement of the constitutional rights of religious minorities.

- Article 14 is violated through targeted discrimination and differential protection.

- Article 15 is breached when segregation, exclusion, or targeted hostility is encouraged.

- Article 19(1)(b) is compromised when minorities face intimidation from peaceful assembly or public expression.

- Article 21 is infringed through threats, coercion, and erosion of dignity.

- Article 25 and 26 are directly violated when prayer meetings are raided, religious practices disrupted, or Christian and Muslim institutions are targeted.

These violations operate not as isolated incidents but as a pattern of parallel sovereignty, where a non-state actor informally asserts the authority to regulate religion, intimacy, public space, and personal liberty. The most profound injury is to the principle of secularism, a core element of India’s basic structure. When the state tolerates a majoritarian organisation exercising coercive power, secularism becomes formal rather than substantive—its guarantees present in doctrine but eroded in lived reality.

Democratic risks and the normalisation of anti-minority governance

AHP–RBD’s six-month mobilisation points to a deeper institutional and cultural shift in India’s democratic landscape: the movement from a pluralist constitutional democracy to a majoritarian quasi-democracy, where minority rights exist formally but are systematically hollowed out in practice. This degradation does not occur through the formal suspension of rights or emergency powers. It occurs gradually, through the normalisation of communal hostility, which reshapes public behaviour, institutional norms, and the emotional structure of citizenship.

The first democratic risk arises from the de-legitimisation of constitutional norms. When communal mobilisation saturates public life, principles such as equality, religious freedom, and secular governance come to be seen not as foundational commitments but as obstacles to majoritarian will. Hate speech, demographic alarmism, and ritual militarisation generate an affective climate in which constitutional protections appear indulgent or even dangerous. In such a climate, minorities internalise fear, withdraw from public spaces, limit political participation, and experience democratic life on unequal terms. Electoral politics, too, becomes distorted: communal consolidation strengthens the majority vote, while minority voting becomes fraught with risk and reduced in impact.

A second democratic risk lies in the erosion of institutional neutrality. The dataset records repeated instances of police presence at events where inflammatory or openly violent rhetoric is delivered. The appearance of state authorities alongside vigilante actors produces a symbolic convergence between law and majoritarian sentiment. Law enforcement shifts from being an impartial guarantor of rights to an instrument of communal policing. When institutions fail to enforce constitutional norms, they lose legitimacy, and alternative power centres—majoritarian groups acting as de facto police—step into the vacuum.

The third democratic risk concerns the cultural redefinition of citizenship. AHP–RBD’s discourse fuses Hindu identity with national identity, constructing Muslims and Christians as conditional citizens whose loyalty must be proven and whose rights may be restricted. Citizenship becomes implicitly ethnoreligious, not civic. Such a transformation strikes at the core of the Indian constitutional order, which deliberately rejects indigeneity, religious majoritarianism, and racialised belonging as bases for citizenship. When minorities are framed as perpetual suspects, their participation in democratic life becomes precarious, and the republic shifts toward graded membership.

The final democratic risk is long-term polarisation. Hate mobilisation produces enduring harms: intergenerational fear, mutual distrust, and hardened communal identities. This polarisation is not limited to politics—it reshapes everyday life. Markets segregate, schools become communally divided, workplaces grow tense, and neighbourhoods fracture into hostile enclaves. Over time, these micro-segregations accumulate into structural separation, weakening the social cohesion that democracy requires. A society fragmented by fear cannot sustain collective governance, universal rights, or shared public institutions.

Together, these dynamics illustrate how AHP–RBD’s activities create not just immediate threats but a systemic democratic recession—a gradual hollowing of constitutional citizenship, institutional neutrality, and pluralist democracy.

Conclusion- The architecture of hate as parallel sovereignty

AHP–RBD’s events and the collated data reveals a sophisticated, multi-layered architecture of hate—one that operates not as episodic violence but as an emergent political order. This order is parallel to the constitutional state, majoritarian in ethos, and vigilante in practice. Through demographic panic, gendered control, ritual militarisation, territorial revisionism, anti-minority surveillance, and the normalisation of extra-legal punishment, AHP constructs a rival normative universe—a universe in which communal identity determines legitimacy, violence becomes moral obligation, and constitutional authority is displaced by militant religiosity.

This phenomenon is not merely a danger to India’s minorities. It is a profound challenge to the foundations of democratic life. When an organisation can redefine belonging, police intimacy, weaponise devotion, rewrite history, and regulate public space—often with the tacit tolerance or visible presence of state authorities—the very idea of citizenship becomes contingent. The rule of law fades into selective enforcement. The secular, civic character of the Republic becomes fragile, overshadowed by ethnoreligious belonging.

India is witnessing a deeper cultural shift:

—from pluralism to purity,

—from rights to obedience,

—from law to spectacle,

—from coexistence to conquest.

No democracy can survive the institutionalisation of hate as common sense. No constitutional order can endure when non-state actors are permitted to wield coercive power with impunity. No society can remain cohesive when its people are divided into protectors and threats, insiders and intruders, pure and polluted.

The challenge before India is therefore greater than the task of curbing a single extremist organisation. It is the task of reclaiming the constitutional imagination. This requires the restoration of institutional neutrality, the impartial enforcement of criminal law, renewed political commitment to equality and dignity, and a cultural repudiation of the politics of fear. It requires civil society vigilance and political courage that refuses to normalise hate.

AHP–RBD’s mobilisation is not the story of a fringe group. It is the story of a parallel polity—one that is emerging, expanding, and asserting influence. Whether this parallel polity becomes embedded in India’s future depends on how institutions, courts, political parties, and citizens respond to the early warning signs documented in this dataset.

The Constitution’s text remains intact. Its lived reality, however, is under deep strain. Even reduced to a hollow shell, some would argue.

The trajectory revealed here is not inevitable—but it is unmistakable. To confront it is not merely an analytical task for scholarship. It is a democratic imperative, central to safeguarding India’s identity as a plural, secular, constitutional republic.

Reference:

The Radical Flank Effect in Social Movements: Evidence from India

Hindutva Radicalisation of the Indian Youth and Its Impact on Freedom of Religion

The Hindu Far-Right and the Indian State: A Study of Vigilante Justice

Ideology and Organizational Strategy of Hindu Nationalism

Inequality, elections, and communal riots in India

The Political Economy of Religious Conflict in India

A Critical Study of Religious Polarization and Its Impact on the Secular Fabric of Indian Society

Profile: Pravin Togadia and the Rise of the Hardline

The Unimportance of Being Pravin Togadia: An Organizational Analysis

CJP moves NCM over Pravin Togadia’s communal oath at ‘Trishul Diksha’ event

Sheath the swords, while there is still time! (Report on AHP’s ‘Trishul Diksha’)

Hate Watch: Pravin Togadia administers communal and anti-minority oath in Haryana

RSS, Togadia decide to work together to ‘unite’ Hindus

India’s ‘love jihad’ conspiracy theory turns lethal

VHP releases over 400 alleged ‘Love Jihad’ cases; to launch awareness against religious conversion

How a ‘love jihad’ case was manufactured in India’s Uttar Pradesh

Hundreds In Mumbai March Against ‘Love Jihad’, Demand Anti-Conversion Laws

Nanded police book Pravin Togadia for hate speech

India Hindu leader in ‘hate speech’ row (2014 report on property eviction call)

Election Commission directs FIR against Pravin Togadia for ‘hate speech’

Togadia’s ‘hate speech’ video under EC scanner

Maharashtra Police registers case against VHP leader Praveen Togadia for hate speech

Pravin Togadia’s claim of being targeted by Modi govt not new

https://www.csohate.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Hate-Speech-Events-in-India_Report_2024.pdf

https://www.pudr.org/publicatiosn-files/2023-04-17-Jahangirpur-%20communal-incident.pdf

[1] A look at the analyses of hate speeches here (https://sabrang.com/cc/archive/2003/may03/index.html), Togadia, then squarely with the Viswa Hindu Parishad (VHP) declares his/and organizational hate and harm-filled intent: to generate anarchy and anti-minority violence (civil war) in every village of the country. Neither logistics not resources have stymied this cancer surgeon who’s Dhanwantri Hospital in Ahmedabad was also noted for its refusal to treat patients belonging to the mass-harmed Muslim minority in February-March 2002. (https://sabrang.com/cc/archive/2002/marapril/hospital.htm, https://sabrang.com/tribunal/vol2/pubspace.html)