“… In the little world in which children have their existence whosoever brings them up, here is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injustice. It may be only small injustice that the child can be exposed to; but the child is small, and its world is small…”

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

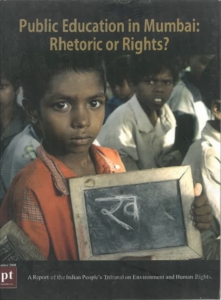

Much of a child’s socialization process revolves around schooling. This report asks the reader to “see with a child’s eyes, hear with a child’s ears, and feel with a child’s heart”. In this report, the IPT presents its findings and recommendations regarding public education in Mumbai to government officials and the public. The report documents children’s parents’ and teachers’ experience vis-a-vis municipal schools in Mumbai. It also presents data and facts that are useful for policy makers and activists in order to debate and discuss the future of municipal schools and public education in Mumbai. It urges the government to take strong measure to address the issues highlighted in the following pages.

This report is the outcome of a public hearing on schooling in Mumbai, which took place on 1 and 2 July 2006. This enquiry into the public education system is different from enquiries into catastrophic events violating human rights. However, the revelations here represent one of the greatest tragedies silently unfolding in modern India. In fact the horror is hidden in the silence. The findings of the Tribunal are distressing, to put it mildly. Denial of quality education to such large numbers of children in Mumbai has not only seriously reduced their right to equal opportunity; it has also damaged their prospects for a better future.

This state of affairs is not a sudden development. It is deeply rooted in India’s social and political history. A brief overview of these developments is presented in order to give perspective to the challenges facing public education in Mumbai today.

Access to knowledge is equal to access to power. For centuries in almost all parts of the world, this power has been controlled by a minority of people and denied to the majority- India is no exception. Ancient Indian mythology has several examples, such as Eklavya and Shambuka, that attempt to justify unequal access to knowledge. The varna system institutionalised this notion of ascribed status through religion, where access to knowledge and skills was pre-ordained for some, with others, such as women and the lower castes, excluded. For more than three thousand years, this condition remained largely unchallenged, with the exception of the work of the Buddha and, later the work of the poet saints in the thirteenth century.

The advent of British rule brought about some fundamental changes- at least initially. During this period, political and economic upheavals in Europe were challenging the power and authority of the feudal lords and the Church. Two such examples were that of French revolution in 1789 and the Industrial revolution in. Echoes of the changes brought by these two revolutions slowly reached the colonized Indian sub- continent. Consequently, in 1813 the East India Company began its official support of formal education in the sub- continent- almost a century after its arrival in India. For the first time, access to formal education was nationally open to all regardless of caste and gender. The wealthy upper-

caste men had initially been the only ones to have the benefit of ‘Western’ education, however the scenario gradually began to change.