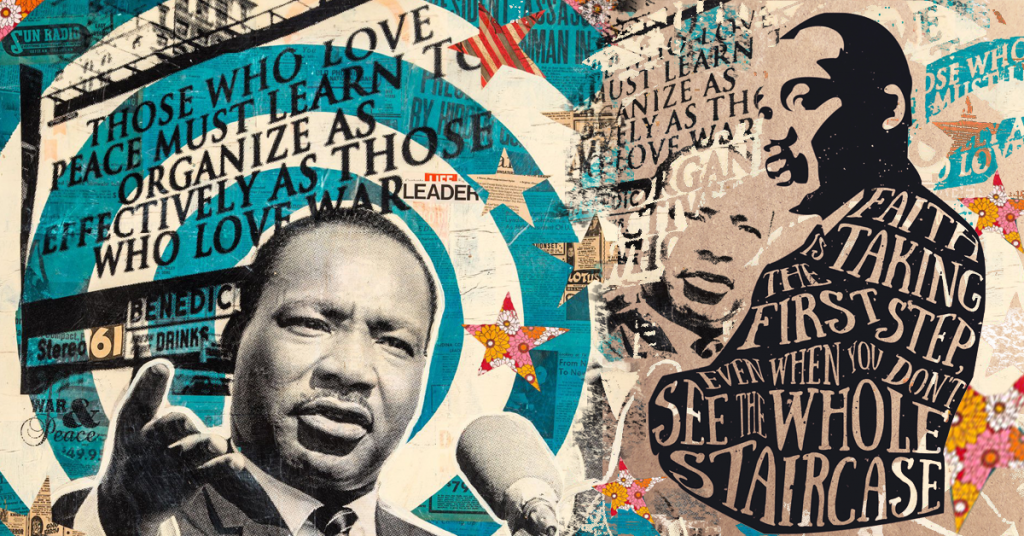

In the language of social justice today, when ‘allyship’ is and should be actively discussed, one can think of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a civil rights leader who not only campaigned because, as an African American, he was oppressed, but also campaigned for others not like him who were also oppressed, albeit in different ways. Here is a brief account of his extraordinary life and inspiring words that helped lift millions out of oppression.

Early Life

On January 15, 1929, Martin Luther King, Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia, to African American parents, Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King. Growing up, he attended a segregated high school, where he was known for oratory skills; at 15, he was admitted to Morehouse College, a prestigious historically black college. While at Morehouse, King decided to enter the ministry, with the opinion that the church was the best possible path to channel his “inner urge to serve humanity”. His “inner urge” would carry Dr. King for the rest of his too-short life.

Civil Rights Activism

On March 25, 1965, Dr. King, along with a 25,000-strong crowd, marched from Selma to Montgomery (both in Alabama) “in support of voting rights for African Americans.” In Montgomery, Dr. King delivered his ‘How Long, Not Long’ speech, famously suggesting that racial prejudice would not be long-lived, “because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” The question remains, then, at what juncture can we see this bend towards justice? Education strategist Deborah Bial, in her commencement speech at Mount Holyoke College in the United States in 2014, opined that “history is not linear. It doesn’t guarantee us progress or solutions and sometimes we move backwards,” noting King’s line about the arc and saying, “but I would add that it does so only under tremendous and constant pressure.”

Dr. King’s work was focused not only on combating racial prejudice, but also on protesting against economic injustice. He delivered his historic ‘I Have A Dream’ speech at 1963’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Rachel Goodman, staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), writes, “From the beginning, the civil rights movement sought economic justice, as well as racial justice,” noting that Dr King, in 1968 said, “What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t have enough money to buy a hamburger?” According to Nicole Kief of the ACLU, a poster for the March on Washington read, “Millions of citizens, black and white, are unemployed…As long as black workers are disenfranchised, ill-housed, denied education and economically depressed, the fight of white workers for a decent life will fail.” Kief notes that the organisers of the march knew “the floor had to be raised for all Americans. They also understood that people of color bore the brunt of economic hardship.” Years before the term “intersectionality” was coined to understand how different forms of oppression can interact, Dr. King and civil rights leaders seemed to be cognizant of this notion, knowing that people were not truly free unless they were free in all senses, and understanding that if one of us is not free, then all of us aren’t.

MLK and Non-violence

In 1959, King, an admirer of Mahatma Gandhi, travelled to India, which reaffirmed his stance on nonviolent protest; “Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity,” he said in a radio address on his last night in India. However, April Reign, founder of the #OscarSoWhite campaign, writes for History that by the time he died, Dr. King’s “language had become stronger and more assertive, urging direct action to bring about change. For King had never meant nonviolent protest to mean ‘wait and see.'” Reign notes that weeks before his assassination, Dr. King told “a packed high school gym” near Detroit that “…it is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society,” adding, “And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.” In his famous ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’, when he was arrested during the campaign against racial segregation in Birmingham, Alabama, Dr. King opined that “the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”.

Reign highlights Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign, launched in the year he was assassinated, “which appealed to impoverished people of all races, and sought to address the issues of unemployment, housing shortages and the impact of poverty on the lives of millions of Americans, white and black.” In the language of social justice today, when ‘allyship’ is and should be actively discussed, one can think of Dr. King as a civil rights leader who not only campaigned because, as an African American, he was oppressed, but also campaigned for others not like him who were also oppressed, albeit in different ways. Dr. King famously delivered his ‘Beyond Vietnam’ speech in New York City in 1967, fiercely criticising the US government for its actions during the ongoing Vietnam War.

And Justice for All

The truth remains, that if one of us isn’t free then none of us truly is. Or, as Dr. King said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” On this Martin Luther King Day, when many will volunteer in memory of one of the foremost human rights defenders in history, it is important to think about how one can be a steadfast ally. In her piece, Reign writes, ‘”Accomplice,’ not ‘ally,’ should be the goal. An ally is one who acknowledges there is a problem. An accomplice is one who acknowledges there is a problem and then commits to stand in the gap for those less fortunate than themselves, without hope or expectation of reward. An ally is passive; an accomplice is active.” Today, too many of us are satisfied with knowing that we believe the right things. That is not enough, nor is it acceptable to be like the white moderates Dr. King mentioned, supporting a cause but wanting to ‘keep the peace’. “It was King’s desire that we each examine our role in the fight for civil liberties, justice and equality,” Reign writes. The question that each of us must ask is, “What kind of pressure am I exerting to further bend the arc of the moral universe towards justice?”

MLK’s most famous speeches:

The ‘How long, not long’ speech

The ‘Where do we go from here’ speech

| Help CJP Act on the Ground: Citizens Tribunals, Public Hearings within Communities, Campaigns, Memoranda to Statutory Commissions, Petitions within the Courts. Help us to Act Now. Donate to CJP. |