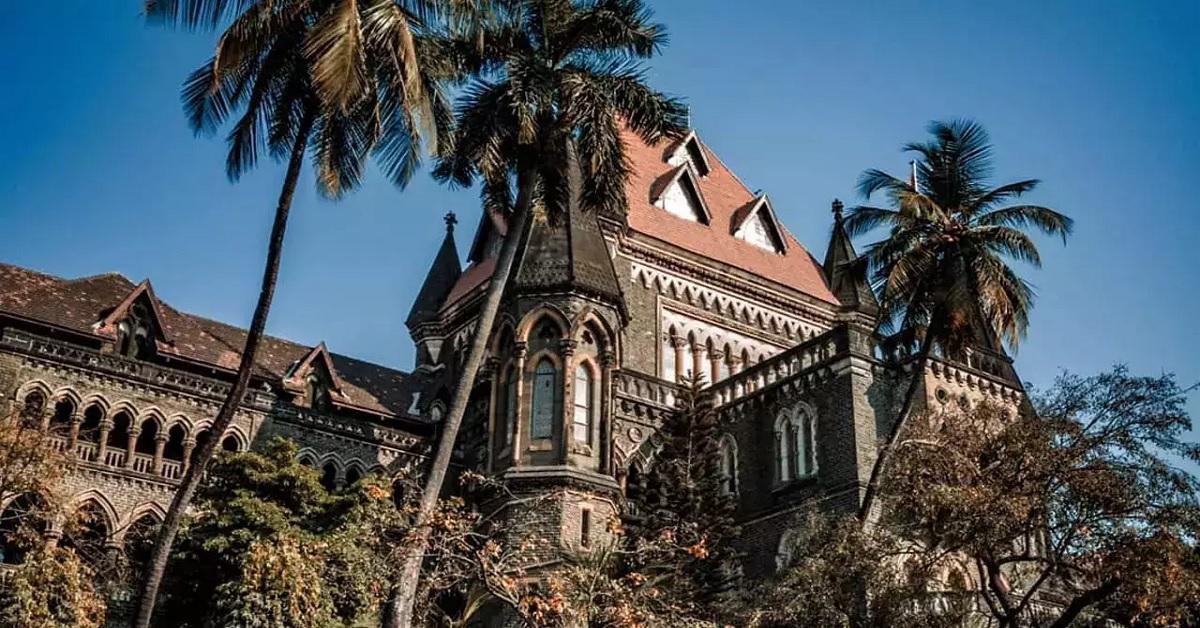

On September 26, 2024 in a pivotal decision, the Division Bench of Bombay High Court struck down the Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rule of 2021 (amended in 2023) as violative of the provisions of Articles 14, 19(1)(a), 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution and fundamental principles of natural justice. The court held that the controversial amended rule is also ultra-vires of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (Act of 2000) itself as the provisions do not meet the conditions provisioned under Section 79 of the Act. The ruling also criticised the Central government’s attempt to establish Fact Check Units (FCUs) to identify “fake or false or misleading” information about its business on social media and other digital platforms while acting as a sole arbitrator in the process of censoring information through the amended Rule.

A Division Bench of Justices A.S. Gadkari and Dr. Neela Gokhale had first heard the matter. After contrary findings, the opinion rendered by the 3rd “tie-breaker judge” Justice A.S. Chandurkar, now forming the majority opinion, settled the matter. The amendment dated April 6, 2023 to Rule 3(1) (b)(v) of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 have therefore been declared unconstitutional and have been struck down.

The Bombay High Court’s landmark decision has signaled a significant victory for freedom of speech and expression in India. Justice Chandurkar’s opinion struck down Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the IT Rules, 2021, amended in 2023, citing violations of Articles 14, 19(1)(a), and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. This ruling is also a resounding affirmation that citizens have the right to free speech, and it is neither the state’s business nor burden to ensure the authenticity of information, or to filter information in public domain –especially with relation to government policies and programmes—on social media platforms and intermediaries.

Background

On April 6, 2023, the union government –then in its second term — notified the controversial amendment to the The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021. Through this amendment of 2023, Rule 3(1)(b)(v) was inserted by the union government enabling the central government to setting-up Fact Check Unit (FCU) to identify “fake or false or misleading” information in respect of any business of the government.

The amendment rule that was notified on April 6, 2023, stipulated that the intermediary (a service provider who receives, stores or transmits any electronic record and provides any service relating to such record on the behalf of another person) shall make reasonable efforts by itself and cause the users of its computer resource to not host, display, upload, modify, publish, transmit, store, update or share information that related to the union government’s activities/businesses.

When legislated, this amended rule was widely criticised as being part of government overreach over the citizen’s right to sharing and expressing of information and also sparked concern about the government’s pre-planned censorship move over the intermediaries and online discourse.

Feeling aggrieved by the new regulations, political satirist and comedian Kunal Kamra moved the Bombay High Court on April 10, 2023. The Association of Indian Magazines and the Editors Guild of India, also filed writ petitions before the Bombay High Court challenging the constitutionality of this provision. Through his petition, Kamra, particularly, argued that these rules not only strangle freedom of expression and speech but also defy natural justice while infringing upon Article 14, 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(g), going beyond the boundaries set by Section 79 of the IT Act, 2000.

The petition laid down how the broad and vague terms used in the rules, such as “fake,” “false,” or “misleading,” had a serious potential for misuse. They could lead to self-censorship among social media users, causing an undue suppression of free speech resulting from the mere possibility of unconstitutional government overreach on the freedom of speech and expressions, protected under Article 19 of the Indian Constitution. His petition argued that the IT Rules 2023 violate his right to carry out his profession as a political satirist under Article 19(1) (g). In his petition Kamra apprehended that his content was likely to be hand-picked by the FCU for “action”, potentially making him the object of arbitrary censorship and suspension from social media.

Kamra relied upon the decision of the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal, in which Section 66A of the IT Act was struck down because it suffered from the ‘vice of vagueness’. He demanded a similar directive from the court against the Amended Rule of 2021, highlighting that the phrase “business of the Central Government” is both “overbroad and vague.” Kamra’s petition argues that the IT Rules 2023 impose excessive restrictions on free speech, going beyond the reasonable limits set by Article 19(2) of the Indian Constitution.

Facts of the case:

The validity of Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 as amended on April 6, 2023 was challenged before the Bombay High Court through batch of writ petitions concerning the censorship and government surveillance over the intermediaries and chilling effect on the aspect of freedom of expression as there was no fundamental right restricted to true and correct information so as to enable the FCU to determine information that was fake or false or misleading with regard to business of the Central Government.

The preliminary contentions of the petitioners before the bench were that the said rule is arbitrary and ultra virus to the Articles 14, 19(1) (a) and 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution and against the principle of natural justice. Submissions of the petitioners ranged on a wide range of issues.

The first proceeding against the challenge was decided on January 31, 2024, in which the Division Bench of Bombay High Court consisting Justices G.S. Patel (now retired) and Dr. Neela Gokhale delivered their split verdict over the survival of the impugned rule.

Justice Patel’s upheld the challenge raised on behalf of the petitioners and declared that the impugned Rule was ultra vires the provisions of Article 19(1) (a) read with Article 19(2), Article 19(1)(g) read with 19(6) and Article 14 of the Constitution. He further held that it was also violative of the principles of natural justice as well as ultra vires Section 79 of the Act of 2000 and failed to satisfy the test set out in the decision in Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal vs. Union of India, 2015 INSC 257, especially on the aspects of overbreadth and vagueness.

(Para 207 of the 31.01.2024 Judgement)

Justice Patel accepted the submissions that the classification inserted under the said impugned Rule is against Article 14 of the Constitution. Justice Patel through his judgement also expressed disagreement, with the issues listed for identification by the Union Government for possible action under the FCU. While questioning the government on this point, Justice Patel remarked that there is no particular reason why information relating to the business of the Central Government should receive ‘high value’ speech recognition, more deserving of protection with a dedicated cell to identify that what is fake, false or misleading, as opposed to precisely such information about any individual or news agency. He added that separating out the business of the Central Government for preferential treatment is class legislation, not a rational or permissible classification.

(Para 209 of the 31.01.2024 Judgement)

He pointed out that the information relating to the business of the Central Government, there is no material at all of any particular “Public Interest” or “National Interest” peril – and these are not even within the permissible parameters of Articles 19(2).

(Para 209 of the 31.01.2024 Judgement)

Justice Patel held that without any working protocol, guidelines or yardstick, there was every possibility that government action could result in overreach to handpicked content and without any requirement of the processes to be followed.

(Para 210 of the 31.01.2024 Judgement)

On the other hand, in her differing judgement, Justice Dr Neela Gokhale came to the conclusion that the said Rule not violative of Articles 14 and 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India. She held that the said Rule was not ultra vires the provisions of the Act of 2000 nor was it contrary to the judgment of the Shreya Singhal (Supra). The Judge also held that the exemption under Section 79 of the Act of 2000 would cease to operate only if the offensive information as provided in the said Rule affected any restriction under Article 19(2) of the Constitution of India. Justice Gokhale further added that the amended Rule did not violate principles of natural justice even though the ground that the FCU compromised of only government officials!

Justice Gokhale affirmed the setting-up of FCU by Central Government for identification of “fake or false or misleading” information related to Central Government’s business on (the petitioner’s) ground that there was potential for abuse by the FCU– on the basis of apprehension– was not maintainable and to that extent the challenge was premature. Against the contentions of the petitioners that the word “fake” or “false” or “misleading” suffering from vice of vagueness, Justice Gokhale held that the words “fake” or “false” or “misleading” as found in the amended Rule were to be understood in the ordinary sense of their meaning and that the said Rule did not suffer from the vice of vagueness. It also met the test of proportionality and the measures adopted by the Government were consistent with the object of the law.

Notably during the hearing of the challenge before the Division Bench, on 27 April, 2023, a statement was made before the Division Bench by the additional Solicitor General Anil Singh appearing on behalf of the Union that the FCU contemplated by the Rule in question will not be notified until July 5, 2023. The Division Bench accepted the statement of the ASG, noting that “without a Fact Check Unit being notified (FCU), the Rule cannot operate” and even if the case were to be heard for ad interim relief, it would “require a full hearing covering all the grounds that are likely to be covered in a final disposal”. The statement which was made on behalf of the Union of India was extended from time to time on 11 occasions.

Later, on September 29, 2023, the statement was extended by the Solicitor General Tushar Mehta until the final judgement is delivered.

A detailed analysis of the previous judgement dated January 31, may be read on Sabrang India Importantly, Justice Patel in his judgement observed that the third judge would decide the interim application seeking direction to the Union not to notify the FCU as the Division Bench was in disagreement on this aspect as well.

However, Chief justice DK Upadhyaya of Bombay High Court, assigned the matter to a third “tie-breaker-judge” Justice A.S. Chandurkar after the after the Division Bench of Justice Gautam Patel and Justice Neela Gokhale delivered a split verdict on January 31, 2024.

The Judgement dated January 31, .2024 may be read here:

Bombay High court refused to stay the FCU Notification

On February 6, 2024, apprehending the Union Government’s intention to form FCU, a bunch of applications filed before Justice A.S. Chandurkar, seeking directions to the government for a stay on the notification of the FCU pending till the final disposal of their pleas against the IT Rules. At this hearing, the court declined the stay on March 11, 2024.

Senior advocate, Darius Khambata argued before the High Court that the statement which was made before the High Court on behalf of the Union of India to the effect that the FCU would not be notified “until final judgment is delivered” would, in the normal course of events, have to be treated as continuing in force until the judgment is pronounced by the third Judge, to whom the adjudication in pursuance of the difference of views between the two judges of the Division Bench is assigned. He further added that a final judgment would emerge only after the decision of the third Judge which would have a bearing on the final outcome.

Union Government notified FCU under IT Rules 2021 on March 20, 2024

Following the rejection of interim relief on March 11, 2024, the Union Government issued a notification on March 20, 2024 whereby the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) notified the Fact Check Unit (FCU) under the Press Information Bureau (PIB) of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB) as FCU of the Central Government under the Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021. The Notification which was published in the Gazette of India reads as follows:

“In exercise of the powers conferred by sub- clause (v) of clause (b) of sub-rule (1) of rule 3 of the Information Technology Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code Rules, 2021, the Central Government hereby notifies the Fact Check Unit under the Press Information Bureau of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting as the fact check unit of the Central Government for the purposes of the said sub-clause, in respect of any business of the Central Government.”

Supreme Court stays the Union’s Notification constituting the FCU on March 21, 2024

The Editors Guild of India and other appellants approached the Supreme Court against the Bombay High Court’s single judge bench order dated March 11, 2024, refusing to stay the implementation of the Rules and the impugned notification issued by the Union Government on dated March 20, 2024, notifying the FCU under the PIB. On March 21, 2024, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court consisting CJI D.Y. Chandrachud, Justices JB Pardiwala and Manoj Mishra set aside the Bombay High Court’s order dated March 11, 2024, rejecting the stay applications filed against the notification of FCU under the Rule challenged before the Court.

The three-judges bench led by CJI DY Chandrachud observed that the challenge which is pending before the Bombay High Court raises core values impinging on the freedom of speech which is protected by Article 19(1) (a) of the Constitution. Hence, since all the issues await adjudication of the High Court, the Supreme Court stated that “we are desisting from expressing an opinion on the merits which may ultimately have the impact of foreclosing a full and fair consideration by the third Judge of the High Court”.

(Para 24 of the Supreme Court order dated March 21, 2024)

The bench directed that “we accordingly set aside the opinion of the third Judge dated 11 March 2024 declining interim relief and direct that pending the disposal of the proceedings before the High Court, the notification of the Union Government in the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology dated 20 March 2024 shall remain stayed.”

(Para 25 of the Supreme Court order dated March 21, 2024)

The Supreme Court, without going into the merits of the pending challenge to the Rules before the Bombay High Court, held that the Notification issued on behalf of the Union Government through Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology dated March 20, 2024 would remain stayed pending disposal of the proceedings before the High Court.

The judgement of Supreme Court dated March 21, 2024 may be read here:

Reference against the Division Bench decision dated January 31, 2024

The matter was then referred to Justice A.S. Chandurkar by the Chief Justice of Bombay High Court, Justice Upadhyay. The reference was rendered for seeking an opinion on the points of difference recorded by the judges constituting the Division Bench and delivered the judgement on January 31, 2024, in which Justice Patel upheld the challenge to the Amended Rule of 2021, struck down the amendment. On the other hand, Justice Dr. Neela Gokhale through her differing judgement upheld and affirmed the validity of the Amended Rule and setting up of FCU.

The points of disagreement between both the judges were not discussed by Justice Chandurkar as the Division Bench in its decision dated February 2, 2024 while considering the Interim Applications observed in paragraphs 3 and 4 of the judgement that it was not necessary to note the points of disagreement or difference since the parties to the proceedings agreed that there was disagreement on every aspect of the matter.

Then the third “tie-breaker judge” Justice Chandurkar expressed his opinion on the question that;

Whether the impugned Rule was or was not ultra vires and unconstitutional?

And the difference of opinion on the principal question arising in the writ petitions that;

Whether the provisions of Rule 3(1) (b) (v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 are unconstitutional or not?

Submissions on behalf of the petitioners

Senior advocate Navroj Seervai, argued the case on behalf of the Kunal Kamra in W.P. (L) No. 9792 of 2023 before the single judge bench of Justice A.S. Chandurkar. The arguments of the Seervai encompass the following areas:

Violates Article 14 of the Indian Constitution

The petitioner’s challenge is based and was argued on the violation of the provisions of Article 14 of the Constitution. The said rule was in the nature of class legislation and was thus liable to be struck down on the aspect of discriminatory classification. He also added that on this issue, no opinion was expressed by Dr. Gokhale J and thus it would not be necessary for the Reference Court to go into this aspect.

Against the principles of natural justice

The petitioner also challenged the impugned Rule on ground of violating the principles of natural justice. The impugned rule did not satisfy the test of natural justice especially on the ground of failure to issue any notice to an intermediary before taking any steps under the Rules of 2021 or in providing any opportunity to an intermediary to respond as well as absence of any requirement on the part of the FCU to issue a reasoned speaking order.

Seervai pointed out that the said challenge is based on breach of principles of natural justice. Dr. Gokhale J considered only the aspect of bias and held against the petitioners. Hence, on the facet of breach of principles of natural justice, other than the issue of bias, there was no differing opinion expressed by Dr. Gokhale J.

(Para 10 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Sr. Adv. Seervai mentioned that while Patel J upheld the challenge raised to the invalidity of Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023, the said provision was found to be valid by Dr. Gokhale J subject to the rider recorded in paragraph 61(i) of her judgement.

(Para 11 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

The expression “knowingly and intentionally” not qualified in the Amended Rule

Seervai further submitted that the requirement of “knowledge and intent” was read in the said Rule in a manner that was against the first principles of interpretation of statutes. He added that the expression “knowingly and intentionally” did not qualify the amended Rule and hence it was not permissible to read the said expression in the impugned Rule. It was urged by the petitioner that the word “information” having been defined by Section 2(1)(v) of the Act of 2000 as an inclusive expression, it could not be given a restrictive meaning so as to encompass facts alone.

(Para 11 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

It was argued that reading in the possibility of a “disclaimer” in Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended was not permissible in the light of settled principles of statutory interpretation.

(Para 11 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

The term “business of the Central Government”, vague and unconstitutional

In relation to the expression “business of the Central Government”, it was underscored by the petitioner that despite finding the term, “business of the Central Government” to be vague, the validity of the impugned Rule was upheld by Dr. Gokhale J. The expression “business of the Central Government” was a term of widest import as held by Patel J. In absence of any indication whatsoever as to what would constitute “business of the Central Government”, the same was vague thus rendering it constitutional. The petitioner pleaded that despite his contentions, its validity was upheld on untenable grounds.

The petitioner while highlighting the eight heads under Article 19(2), submitted that the impugned Rule did not make any attempt to limit the restrictions to the eight heads under Article 19(2) of the Constitution of India and sought to impose restrictions beyond what was permissible under Article 19(2). In fact, a ninth restriction was sought to be introduced by the impugned Rule. The Petitioner placed reliance on the decision of the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal (Supra), he added that the government was made a similar attempt while defending the validity of Section 66-A of the IT Act, 2000 which was declared unconstitutional by this court. It was legally not permissible to expand the nature of restrictions prescribed under Article 19(2) through an interpretative process.

(Para 12 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

In support, the petitioner relied upon the decision of the Supreme Court in Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India and others vs. Cricket Association of Bengal and others, (1995) 2 SCC 161, in which the court held that no restriction could be placed on the right to freedom of speech and expression on grounds of other than those specified under Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

Notably, the petitioner urged that “the amended Rule was also violative of Article 14 of the Constitution inasmuch as it resulted in class legislation. It sought to counter a perceived ill of only one entity, namely the Central Government. There was no reason or rationale behind limiting its operation only to the “business of the Central Government” while excluding the State Governments. There was absence of any intelligible differentiation”

(Para 13 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Central Government was also to be judge in its own cause: violates natural justice

It was submitted by the petitioner that amended Rule was also violative of the principles of natural justice inasmuch as the Central Government itself was to constitute the FCU and was also to be a judge in its own cause for determining the content of information to be fake or false or misleading. This was contrary to the law laid down in A.K. Kraipak and others vs. Union of India 1969 INSC 129.

He further emphasised that absence of an opportunity of hearing to the person likely to be affected, absence of knowing the basis on which the FCU was to determine the content of information to be fake or false or misleading as well as absence of a speaking order rendered the Rule vulnerable to a challenge based on violation of principles of natural justice.

However, the Petitioner submitted before the bench that the impugned Rule suffered from manifest arbitrariness and for all these reasons “it was urged that the view expressed by Patel J that Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 was invalid be accepted.”

(Para 13 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Submission made by the other petitioners

Advocate Shadan Farasat, appeared for Editors Guild of India in W.P.(L) No.14955 of 2023, submitted that Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 was in violation of the provisions of Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. There was no fundamental right restricted to true and correct information so as to enable the FCU to determine information that was fake or false or misleading with regard to business of the Central Government.

Adv Farasat pointed out that “there was no fundamental right restricted to true and correct information so as to enable the FCU to determine information that was fake or false or misleading with regard to business of the Central Government. Even if the operation of the impugned Rule was to be restricted in the manner suggested by the learned Solicitor General, the same would not save it from the vice of invalidity.”

(Para 14 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Farasat added that the contention urged on behalf of Union of India of a disclaimer being provided by an intermediary was not provided under the impugned Rule. In fact, providing a disclaimer would amount to modifying such information which was not permissible under the Rule. He stressed that it was thus clear that the impugned Rule could not be read down in any manner so as to save it from being struck down. Since the Rule was violative of the provisions of Articles 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, it was rightly struck down by Patel J.

(Para 14 of the Judgement dated September 20,2024)

Advocate Gautam Bhatia argued the case on behalf of the Association of India Magazines in W.P. No. 7953 of 2023. He also relied on the similar grounds that impugned Rule was liable to be quashed as being unconstitutional and violative of Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. He cited the observation made by Justice Patel in judgment dated January 31, 2024, while questioning the constitutionality of the setting up the FCU, he underscored that “The FCU appointed by the Central Government itself was made the arbiter of information which it found to be fake or false or misleading. The FCU, being the creature of the Government, it was made a judge in its own cause. There was a large area of information which could be dissected other than as being either true or false. Once the FCU determined a piece of information to be either fake or false or misleading, there was no option for the petitioners but to comply with its directions.”

(Para 15 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Senior advocate Arvind Datar, appeared for NBDA in Interim Application (L) No. 17704 of 2023, submitted that “the impugned Rule had far reaching effect and its implementation would result in a form of media censorship. Since the expression “fake or false or misleading” had not been defined in the Rules of 2021, the basis on which the FCU would undertake identification of fake or false or misleading information was not known. On the ground of vagueness, the said provision was liable to be struck down.”

(Para 16 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“Lack the test under doctrine of proportionality”

Advocate Datar, discussed the aspect of proportionality before the bench. It was submitted that the same had become a part of Indian jurisprudence. There were no safeguards whatsoever provided under the amended Rule so as to satisfy the doctrine of proportionality. He further added that the impugned Rule was violative of the provisions of Article 14 of the Constitution inasmuch as the aspect of restriction on any information being fake or false or misleading was not applicable to the print media but was made applicable to the digital media.

(Para 18 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“Section 147(1)(d) of BNS resulting in a chilling effect on free speech”

With regards to the consequences of the FCU finding information to be “fake or false or misleading”, Adv Datar referred to the provisions of section 147 (1)(d) of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2024. He submitted that on the FCU identifying any information to be violative of the said impugned Rule, would, besides “taking down such content/information”, enjoy the powers to lodge a First Information Report under section 147(1)(d) resulting in a chilling effect on free speech. Since the Press and Information Bureau (PIB) was already established by the Central Government there was no need whatsoever to establish the FCU for undertaking a similar task of identifying fake or false or misleading information.

(Para 20 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Submissions on behalf of Union of India

Tushar Mehta, Solicitor General for the Union of India supported the view taken by Dr. Gokhale J and opposed the submissions made on behalf of the petitioners. He submitted written submission before the court in which he mentioned that Rule 3(1)(b)(v) as amended was valid. He referred to the statutory scheme of the Act of 2000 and especially various definitions in Section 2(1) along with Sections 69-A, 79 and 87 of the Act of 2000. SG also referred to the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023.

“Intention behind the Amending Rule 3(1)(b)(v)”

SG Mehta contended that intention behind amending Rule 3(1)(b)(v) was to prevent the spread and circulation of “fake or false facts in relation to the business of the Central Government.” He further added that the minimum intrusive test had been applied while framing the Rules of 2021 and amending them in 2023. The aspect of proportionality had been kept in mind while doing so and the least restrictive method available had been adopted.

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

It was also submitted by the Union that on any information that was found to be “fake or false or misleading” as regards the business of the Central Government, the option of putting up a disclaimer was available to enable intermediaries to continue to enjoy safe harbour. The tests of proportionality referred to in Gujarat Mazdoor Sabha (supra) were fully satisfied.

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“The right to have correct and filtered information”

SG Mehta while signifying the importance of citizen’s right to information on one step further, urged that “the right to have correct and filtered information was an integral part of the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. If speech or expression was untrue, there was no protection of the constitutional right as held in Dr. D.C. Saxena vs. Hon’ble The Chief Justice of India, 1996 INSC 753.”

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“FCU’s desired application: Print and Digital Media”

In relation to the argument raised by the petitioner that restriction on any information being fake or false or misleading was not applicable to the print media but was made applicable to the digital media, ASG stated that the tests as applied with regard to the print media in Sakal Papers Pvt. Ltd and others vs. Union of India, 1961 INSC 277 and Bennett Coleman and Co and others vs Union of India and others, 1972 INSC 268, could not be applied in the present case.

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“FCU not final arbitrator”

On the submission of the petitioner that Central Government was the final arbiter or determining what information was fake or false or misleading, SG added that it was only the court of law that was the final adjudicator. The remedy of approaching a court of law had not been taken away and hence that remedy could always be invoked in case of any grievance as to a direction issued by the FCU.

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“Chilling effect flowing from Rule 3(1) (b)(v) a mere apprehension”

SG Mehta submitted before the court over the arguments of the petitioners that impugned Rule is a threat of losing safe harbour and the chilling effect on Free Speech, there was no evidence or material before the Court to indicate that after the amendment to Rule 3(1) (b) (v) of the Rules of 2021, a chilling effect had set in. SG referred the observations of the Supreme Court in Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India and others, 2020 INSC 31 and opposed that the contention based on the chilling effect of the aforesaid provision was farfetched and based on mere apprehension. Since the amended Rule was not yet notified. SG Mehta therefore relied on the observation made by Justice Dr. Gokhale and urged before the court that the view taken by Dr. Gokhale J ought to be upheld since all relevant aspects had been duly considered while holding the provisions of Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 to be valid.

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

“Words “fake or false or misleading” were not hit by the vice of vagueness”

While opposing the submissions and the ground of challenge by the petitioners, SG Mehta submitted that a mere allegation of vagueness was no ground for declaring a provision unconstitutional. It was submitted that though in Shreya Singhal (supra) Section 66-A of the Act of 2000 had been set aside on the ground of vagueness, the same was a penal provision. He further urged that the same test could not be applied in the present case as no aspect of personal liberty was involved. It was thus urged that the view taken by Dr. Gokhale J was the correct view and that Rule 3(1) (b) (v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 was not liable to be struck down.

(Para 21 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Justice A.S. Chandurkar’s final judgement of September 20, 2024

On August 8, 2024, the petitioners and respondent union of India concluded their submissions before the single, tie-breaker judge, Justice Chandurkar. On September 20, 2024, Justice Chandurkar delivered his final, rather detailed judgement and held that Rule 3(1) (b) (v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 is violative of the provisions of Article 14, Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution.

Justice Chandurkar through this verdict showed agreement with findings of former HC Judge, Justice Patel. The amended Rule was declared as amended and ultra virus the Act of 2000.

(Para 24 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024))

The final judgement was delivered on the nine points of difference between Justice Patel and Justice Gokhale’s opinion, which are as follows:

Article 19(1) (a) and Article 19(2) of the Indian Constitution

Justice Patel had struck down the impugned Rule as ultra-vires to the Article 19(1) (a) and Article 19(2) of the Constitution and Justice Chandurkar shown his agreement with justice Patel’s findings. He pointed out that in context of Article 19(1)(a) and 19(2), there is no further “right to the truth” nor is it the responsibility of the State to ensure that the citizens are entitled only to “information” that was not fake or false or misleading as identified by the FCU.

He further observed that “I would agree with the view of Patel, J that under the right to freedom of speech and expression, there is no further “right to the truth” nor is it the responsibility of the State to ensure that the citizens are entitled only to “information” that was not fake or false or misleading as identified by the FCU. Rule 3(1)(b)(v) seeks to restrict the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) by seeking to place restrictions that are not in consonance with Article 19(2) of the Constitution.” He further ruled that “I agree that the impugned amendment of 2023 to Rule 3(1) (b) (v) is ultra-vires Article 19(1) (a) and Article 19(2) of the Constitution.”

(Para 36 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Violation of Article 19(1)(g) read with Article 19(6)

Over the challenge, raised by the petitioners based on the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1) (g) of the Constitution has been considered by Patel J in paragraphs 167 to 177 of his earlier judgment and held that a piece of information relating to the business of the Central Government that could find place in print media was not subjected to the same level of scrutiny as is expected under the impugned Rule when that very information is shared on digital platforms. Justice Chandurkar observed that there is no such “censorship” when such material is in print while it is liable to be suppressed as fake or false or misleading in its digital form. “It has thus been held that the impugned Rule resulted in direct infringement of Article 19(1) (g) of the Constitution.”

(Para 37 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Justice Chandurkar while showing his agreement with what has been observed in paragraph 167 to 177 by Justice Patel, wherein the challenge based on violation of the right guaranteed under Article 19(1) (g) of the Constitution has been upheld. Justice Chandurkar held that “There is no basis or rationale for undertaking the exercise of determining whether any information in relation to the business of the Central Government is either fake or false or misleading when in the digital form and not undertaking a similar exercise when that very information is in the print form. The Editors Guild of India is justified in its grievance that it is concerned with both, the print media as well as digital platforms. There is thus an infringement of the right guaranteed under Article 19(1) (g) of the Constitution of India.”

(Para 38 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Violation of Article 14, Govt itself final arbiter in its own cause: Justice Chandurkar

Justice Chandurkar while dealing with a related issue held that that by constituting the FCU, the Government itself became the final arbiter in its own cause inasmuch as the government itself has given itself the power to decide which information was fake or false or misleading. On this issue, Justice Gokhale had held in favour of the government. Justice Chandurkar upheld Justice Patel’s findings that that the Central Government could not be a judge in its own cause and relied upon the decision in A. K. Kraipak & others and in paragraphs 189 to 191 of his (Patel’s) judgment this issue has been considered under the head “Natural Justice”. Justice Chandurkar while agreeing with Justice Patel on this subject, held that another facet of challenge based on violation of Article 14 that has been upheld by Patel J is that what is permissible in the print media is proscribed in the digital form.

“In other words, the test of any information being fake or false or misleading as regards business of the Central Government though applicable for the digital version is inapplicable for the very same information when published in the print media. I thus agree with Patel J that this distinction results in violation of Article 14 of the Constitution” states the judgement of Justice Chandurkar.

(Para 40 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Knowledge and intention

In context of the expression “knowingly and intentionally communicates” appearing in Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended, Patel, J has held that the words “knowingly and intentionally communicates” apply to and qualify the immediately following clause “any misinformation or information which is patently false and untrue or misleading in nature”. They do not control the amended portion which is “or, in respect of any business of the Central Government, is identified as fake or false or misleading by such fact check unit” It has been further explained that with regard to any non-Central Government business related content, there is no FCU and there is no arbiter of what is “patently false and untrue or misleading.”

(Para 42 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Justice Chandurkar said that “it has been rightly observed that with regard to non-Central Government business, the focus is on the user’s awareness of falsity and untruth or misleading nature of information while with regard to Central Government business, the focus is on the intermediary permitting continuance of what the FCU has determined to be fake or false or misleading.” On both this aspects, Justice Chandurkar pointed out that the impugned amended Rule intends to create two different area, one relating to non-Central Government business and the other specifically to the business of the Central Government.

(Para 42 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Expression “fake or false or misleading”

On the another point of difference based on the absence of the actual meaning of the expression “fake or false or misleading” appearing in Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended, he cited the observation made by Justice Patel that various scholarly works in that context and has thereafter found that in absence of any guidelines to indicate the manner in which fake or false or misleading information could be identified by the FCU, Rule 3(1)(b)(v) was vague and overbroad. Justice Chandurkar held that “In my view, absence of any indication as regards the manner of identifying fake or false or misleading information and there being no guidelines whatsoever in that regard renders the expression “vague or false or misleading” to be vague and overbroad.” While striking down the impugned rule on ground of vague and overbroad, Justice Chandurkar held that ‘I would therefore endorse the view expressed by Patel J that in absence of any guidelines under the Rules of 2021 as amended to indicate the scope and applicability of the expression “fake or false or misleading”, the impugned Rule is vague and overbroad rendering it liable to be struck down”

(Para 43 & 44 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

The Impugned Rule being ultra vires the Act of 2000

Importantly, the impugned rule also saw petitioners and the court apply the test under the IT Act 2000 itself. The challenges raised to the impugned rules were also on grounds that it travels beyond the rule making power conferred under the Act of 2000. It also suffers from manifest arbitrariness for not being in conformity with the Act of 2000.

As discussed by Justice Chandurkar in his opinion that, Justice Patel in his decision observed that Section 87(2)(z) of the Act of 2000 contemplates Rules for providing the procedure and safeguards for blocking for access by the public under Section 69A(2). He further highlighted that under Section 87(2) (zg) the Central Government could not create a FCU to identify any information relating to the Government’s business as fake or false or misleading and no such rule making power could be exercised beyond the frame of Article 19(2) of the Constitution. He thus held that the Rule as amended was ultra vires the Act of 2000. Justice Chandurkar added that “In my view, Rule 3(1) (b) (v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 is ultra vires the Act of 2000. Firstly, the amendment of 2023 has not been effected as required by Section 87(3) of the Act of 2000. Secondly, the amended Rule is not referable to Section 87(2)(z) as the said provision relates to the procedure and safeguards for blocking for access by the public under Section 69A(3).

(Para 45 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Chilling effect of the amended Rule

On the challenge to the impugned rule, highlighted by the petitioners during their submissions and later accordingly upheld by Justice Patel that impugned Rule being vague and broad, it has the potential of causing a “chilling effect” on that premise, Justice Chandurkar that “the chilling effect therefore was an aspect that had material bearing as a facet of challenge to the validity of such provision. If it was found that the impugned Rule was also vague and broad without any guiding principle to indicate the areas it sought to encompass, possibility of such chilling effect being felt would be an additional ground to hold it invalid.”

(Para 47 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Justice Chandurkar expressed his opinion in consonance with the observation made by Justice Patel. He observed that “when the totality of the challenge is considered and all grounds of attack are taken together, the fact that the impugned Rule also results in a chilling effect qua an intermediary would render it invalid. On this count, the ratio of the decisions in Kusum Ingots and Alloys Limited vs. Union of India, 2004 INSC 319 as well as S Sant Lal Bharti vs. State of Punjab, 1987 INSC 354 would not be attracted.” (Para 48)In that context, I thus agree with Patel J and opine that the impugned Rule being vague and broad, it has the potential of causing a “chilling effect” on that premise.

(Para 48 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Saving the impugned Rule by reading it down

It was urged before the Division Bench that the Court ought to make an attempt to read down the Rule so as to save it from being struck down. In this regard, Justice Patel held that the submission that the operation of the Rule ought to be limited to information that was fake or false would result in ignoring the expression “misleading”.

Justice Chandurkar stressed that “it was held that the provision under challenge ought to be judged on its own merits without any reference as to how well it would be administered. This is for the reason that any assurance from one Government even if carried out faithfully would not bind a succeeding Government. In my view therefore the impugned Rule cannot be saved by undertaking the exercise of “reading down” as suggested or by accepting the stand of the Union of India of the limited manner of its operation in the context only of “fake or false” information or for that matter putting up a disclaimer being sufficient in itself so as not to deprive the intermediary of any safe harbour.”

(Para 52 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

Aspect of proportionality

In relation to the aspect of proportionality in challenge, Justice Patel has referred to the five-fold test laid down by the Supreme Court in Gujarat Mazdoor Sabha (supra). Justice Patel held that the impugned Rule as amended failed all the five tests laid down by the Supreme Court. The challenge to the impugned Rule on the ground of proportionality was upheld. However, the similar view has been expressed by Justice Chandurkar in agreement with Justice Patel’s view, he observed that “the challenge raised to the impugned Rule as not satisfying the proportionality test has to be upheld especially when it seeks to abridge fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 19(1) (a) and 19(1) (g) of the Constitution of India. Absence of sufficient safeguards against the abuse of the Rules that tend to interfere with the aforesaid fundamental rights are shown to be absent.”

(Para 55 of the Judgement dated September 20, 2024)

The third “tie-breaker judge”, Justice Chandurkar conclusively held that even on the ground of proportionality, the impugned Rule cannot be sustained as observed by Patel J. However, Justice Chandurkar concluded his opinion that Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 is liable to be struck down in agreement with the view expressed by Justice Patel that;

- Rule 3(1)(b) (v) of the Rules of 2021 as amended in 2023 is violative of the provisions of Article 14, Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution.

- The said Rule as amended is ultra vires the Act of 2000.

- The expression “knowingly and intentionally” does not apply to the amended portion of Rule 3(1) (b) (v) in relation to the business of the Central Government.

- The expression “fake or false or misleading” in absence of it being defined is vague and overbroad.

- The impugned Rule cannot be saved either by reading it down or on the basis of any concession made in that regard of limiting its operation.

- The test of proportionality as laid down in Gujarat Mazdoor Sabha (supra) is not satisfied by the impugned Rule.

- Given the totality of the above, the impugned Rule also results in a chilling effect qua an intermediary. (Para 56)

The Judgement may be read here:

Information and Technology Act and Rules

The Information Technology Act, 2000 is the primary legislation as of now to deal with electronic data and information technology. This act harbours a concept called the intermediary. Who is an intermediary? The act defines intermediary as with respect to any particular electronic records, any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that record or provides any service with respect to that record and includes telecom service providers, network service providers, internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online-auction sites, online-market places and cyber cafes. This definition encompasses all current social media giants such as Facebook, Twitter etc.

One of the main functions of this definition can be found in Section 79. Section 79 states an intermediary shall not be liable for the third-party information it does not have connection to and is hosted by a user, provided some conditions are fulfilled. These conditions include the intermediary observing due diligence while discharging his duties under this Act and also observing such other guidelines as the Central Government may prescribe in this behalf.

Simply put, this provision states that in addition to the conditions which are to be fulfilled by the intermediary for it to be not liable for the information hosted on its server, provided it follows the guidelines given by the central government. If the intermediary does not follow such guidelines, the entity would lose the immunity from liability.

In 2011, the government promulgated the Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011 which dealt with the due diligence that is to be observed by the intermediary. There were also the Information Technology (Reasonable security practices and procedures and sensitive personal data or information) Rules, 2011 which dealt with data security and security protocols to be followed by intermediaries etc.

Notably, The Bombay High Court’s landmark decision on September 26, 2024, striking down Rule 3(1) (b) (v) of the IT Rules, 2021, has far-reaching implications for free speech, dissent and democracy in India. By declaring the rule unconstitutional, the court safeguarded citizens’ freedom of expression, preventing arbitrary censorship and the chilling effect on free speech. This verdict limits the government’s unchecked power over online content, ensures proportionate restrictions, and promotes transparency and accountability. It reinforces the principles of democracy, protecting Indians’ access to information and upholding constitutional rights, thereby strengthening the foundations of a vibrant and inclusive digital public sphere.